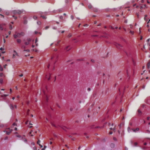

joel bubble ben / shutterstock.com

In a controlled, large-cohort, longitudinal study from Canada, Atiquazzaman et al. found that use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) substantially contributes to increased cardiovascular disease risk among people with osteoarthritis (OA).1

This is the first study to evaluate the mediating role that NSAIDs play in the association between OA and cardiovascular disease (CVD), and the findings show that a significant percentage of the effect of OA on heart disease risk is mediated through NSAIDs.

Although research shows OA is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, “what we didn’t know was why,” says Aslam H. Anis, PhD, FCAHS, professor, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and a co-author on the study.2

“The research gap was understanding the mechanism of the increased risk of CVD among OA patients compared to the general population. People with OA are frequently treated with NSAIDs to control their pain and inflammation, and it’s well known that NSAIDs are associated with cardiovascular adverse effects,” Prof. Anis says.

Many studies also link NSAID use to an increased risk of heart-related events: One 2008 cohort study of 336,906 individuals found that stroke risk was 20% higher for those who used indomethacin and 28% higher for those who used rofecoxib.3 In contemplating these interrelationships, Prof. Anis and his colleagues wanted to investigate the role of NSAIDs in the observed association between OA and CVD, and to better understand the relationship.

Mediating Effect

Atiquazzaman et al. analyzed health administration data from a population-based cohort of 720,055 individuals in British Columbia. They identified 7,743 OA patients matched on age and sex, as well as 23,299 patients who did not have OA as controls. The study’s primary outcome was the risk of developing incident CVD, and the secondary outcomes were the risk of developing ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure and stroke. Their focus was estimating the mediating effect of NSAIDs, which they defined as current NSAID use, on the relationship between OA and CVD.

Based on population-based health administration data from British Columbia’s healthcare system, Atiquazzaman et al. found that people with OA had a 23% higher risk of developing CVD than those without OA. This finding was in line with the results of previous studies, including a 2016 meta-analysis of 15 different observational studies that found a 24% higher risk of CVD among OA patients compared with healthy individuals.4

Prof. Anis

After they adjusted the data for socioeconomic status, body-mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other clinical comorbidities using the Romano comorbidity score, the adjusted hazard ratio for developing CVD with OA was 1.23. The adjusted hazard ratio for developing the secondary outcomes was 1.42 for congestive heart failure, 1.17 for ischemic heart disease and 1.14 for stroke. These findings were similar to those in a 2013 study of 40,817 OA patients co-authored by Prof. Anis that found an almost identical stroke risk in this population.5

The mean age of patients in the Atiquazzaman study was 64.53 years, and approximately 56% were women. A higher percentage of the participants with OA were obese than those without OA. The study sample was equally distributed across different socioeconomic groups. When it came to comorbidities, hypertension and COPD were more common among people with OA than in those without OA, and people with OA had more comorbidities overall.

What is new about this study is that the findings show the mediating effect of NSAIDs on increased heart-related risks. The researchers used a novel methodology proposed by fellow epidemiologists in a 2012 paper, and they evaluated NSAIDs’ mediation of CVD risk in a survival analysis context.6 They found an association of NSAID use for approximately 41% of the increased CVD risk, 23% of the increased heart failure risk, 56% of the increased ischemic heart disease risk and 64% of the increased stroke risk in patients with OA.

Causal, Not Just Confounder

NSAIDs play a major role in increasing the risk of CVD in patients with OA.

“In epidemiological studies, a confounder is defined as a variable that is associated with the exposure and a risk factor for the study’s outcome, but does not lay in the causal pathway. Our hypothesis was that people with OA use more NSAIDs to control the symptoms of pain and inflammation compared to the general population, and that may lead them to develop CVD,” Prof. Anis says. “In other words, NSAIDs are in the casual pathway in the OA-CVD association. We adopted a mediation analysis approach to deconstruct the total effect of OA on increased risk of CVD, and we estimated how much of the total effect is explained by the NSAID use among OA patients.”

One of the strengths of this new study is its novel methodology, including marginal structural modeling in a health administrative data-based cohort, says Prof. Anis. However, it has limitations, including the fact that data on potentially important variables, such as over-the-counter NSAID use, is not included in the healthcare system’s records and was unavailable, so the mediator variable may have been underestimated. Other potentially impactful risk factors for CVD in the OA patient population, such as BMI, smoking, family history of heart disease and physical activity, are not included in the British Columbia healthcare system’s database, the researchers write.

The researchers used a strategy to impute BMI at the individual level using Canadian Community Health Survey data, but they acknowledged it still may be a confounder in this analysis. To further analyze this confounding impact, they conducted a sensitivity analysis with BMI data excluded, but they found little change in the CVD risk for people with osteoarthritis.

Next Steps

Although novel, even disease-modifying therapies for OA are in development now, NSAIDs are still widely used by patients to manage joint pain.7 The 2019 ACR/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip and Knee includes oral NSAIDs as one of its recommendations.8 Thus, it is important for rheumatologists and other healthcare providers to watch for signs of CVD and discuss the risks of NSAID use with their patients, says Prof. Anis.

“We now know that the use of NSAIDs plays a substantial role in developing cardiovascular diseases among people with OA. The findings of this study highlight the importance of monitoring for cardiovascular adverse effects among OA patients,” he says. “Patients should receive counseling so they know the risks and use NSAIDs cautiously.”

Susan Bernstein is a freelance journalist.

References

- Atiquazzaman M, Karim M, Kopec J, et al. Role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular diseases: A longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;71(11):1835–1843.

- Rahman MM, Kopec JA, Anis AH, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with osteoarthritis: A prospective longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013 Dec;65(12):1951–1958.

- Roumie CL, Mitchel EF Jr., Kaltenbach L, et al. Nonaspirin NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and the risk for stroke. Stroke. 2008 Jul;39(7):2037–2045.

- Wang H, Bai J, He B, et al. Osteoarthritis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2016 Dec 22;6:39672.

- Rahman MM, Kopec JA, Cebire J, et al. The relationship between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease in a population health survey: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013 May 14;3(5):e002624.

- Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M. A simple unified approach for estimating natural direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Aug 1;176(3):190–195.

- Ghouri A, Conaghan PG. Update on novel pharmacological therapies for osteoarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2019;11:1759720X19864492.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Feb;72(2):220–233.