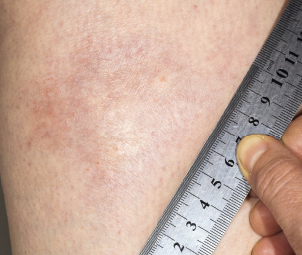

A morphea plaque on the leg.

Dr Harout Tanielian / Science Source

In September 2018, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) granted fast-track status to FCX‑013, a gene therapy product developed to treat moderate to severe localized scleroderma (morphea). Previously, the treatment received an orphan drug designation for localized scleroderma, as well as a rare pediatric disease designation. Phase 1 and 2 studies will assess safety and suggest whether FCX-013 holds promise for this damaging disease, which currently lacks FDA-approved treatments.

Systemic Sclerosis & Localized Scleroderma

The sclerotic disease, scleroderma, can be classified as two distinct autoimmune syndromes: systemic sclerosis and localized scleroderma. Although the latter is thought to only rarely progress to the former, the two share overlapping findings in histology, cell biology and pathophysiology. Systemic sclerosis is characterized by cutaneous sclerosis and deep visceral involvement, whereas localized scleroderma primarily causes skin symptoms. However, localized scleroderma encompasses a spectrum of different skin depths and patterns of lesions. In some subtypes, localized scleroderma may also affect nearby tissues, such as fat, fascia, muscle and bone.1,2

Some confusion exists over terminology, with many rheumatologists preferring the term morphea to localized scleroderma, partly due to concerns that patients may confuse localized scleroderma with systemic sclerosis. However, in some contexts, the term morphea is also used to refer to a specific subtype of localized scleroderma, plaque morphea, the most common subtype found in adults.1,2

David F. Fiorentino, MD, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Dermatology, and the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology at Stanford University School of Medicine, Calif. He points out, “Morphea can be a devastating disease for patients for many reasons—the sclerosis, which can lead to loss of joint mobility and functional disability; the cosmetic disfiguration, caused by dyspigmentation or atrophy; pruritus; and pain.”

No available treatments directly address the underlying disease etiology. Topical and systemic steroids are frequently prescribed. “Current therapies include potentially toxic medications, [such as] methotrexate, which are only modestly effective in a subset of patients,” adds Dr. Fiorentino. “Ultraviolet light therapy is another modality, especially UVA1, but unfortunately these treatment units are only available at select sites in the U.S. and are inaccessible for most patients.”

The majority of patients with localized scleroderma first experience symptoms in childhood.3 Dr. Fiorentino notes that pediatric morphea, in particular, represents a major unmet need, because these patients often have more sclerotic disease that can affect joint function and cause significant pain and disability. The linear subtype of localized scleroderma causes morphea lesions on the trunk or extremities that cross over joints. When it affects the epiphyseal growth plate, permanent limb shortening or atrophy can result.3