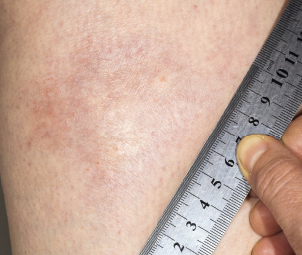

A morphea plaque on the leg.

Dr Harout Tanielian / Science Source

In September 2018, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) granted fast-track status to FCX‑013, a gene therapy product developed to treat moderate to severe localized scleroderma (morphea). Previously, the treatment received an orphan drug designation for localized scleroderma, as well as a rare pediatric disease designation. Phase 1 and 2 studies will assess safety and suggest whether FCX-013 holds promise for this damaging disease, which currently lacks FDA-approved treatments.

Systemic Sclerosis & Localized Scleroderma

The sclerotic disease, scleroderma, can be classified as two distinct autoimmune syndromes: systemic sclerosis and localized scleroderma. Although the latter is thought to only rarely progress to the former, the two share overlapping findings in histology, cell biology and pathophysiology. Systemic sclerosis is characterized by cutaneous sclerosis and deep visceral involvement, whereas localized scleroderma primarily causes skin symptoms. However, localized scleroderma encompasses a spectrum of different skin depths and patterns of lesions. In some subtypes, localized scleroderma may also affect nearby tissues, such as fat, fascia, muscle and bone.1,2

Some confusion exists over terminology, with many rheumatologists preferring the term morphea to localized scleroderma, partly due to concerns that patients may confuse localized scleroderma with systemic sclerosis. However, in some contexts, the term morphea is also used to refer to a specific subtype of localized scleroderma, plaque morphea, the most common subtype found in adults.1,2

David F. Fiorentino, MD, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Dermatology, and the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology at Stanford University School of Medicine, Calif. He points out, “Morphea can be a devastating disease for patients for many reasons—the sclerosis, which can lead to loss of joint mobility and functional disability; the cosmetic disfiguration, caused by dyspigmentation or atrophy; pruritus; and pain.”

No available treatments directly address the underlying disease etiology. Topical and systemic steroids are frequently prescribed. “Current therapies include potentially toxic medications, [such as] methotrexate, which are only modestly effective in a subset of patients,” adds Dr. Fiorentino. “Ultraviolet light therapy is another modality, especially UVA1, but unfortunately these treatment units are only available at select sites in the U.S. and are inaccessible for most patients.”

The majority of patients with localized scleroderma first experience symptoms in childhood.3 Dr. Fiorentino notes that pediatric morphea, in particular, represents a major unmet need, because these patients often have more sclerotic disease that can affect joint function and cause significant pain and disability. The linear subtype of localized scleroderma causes morphea lesions on the trunk or extremities that cross over joints. When it affects the epiphyseal growth plate, permanent limb shortening or atrophy can result.3

Treatment

“There is a tremendous need for new therapies that are effective to address one or more of these issues,” Dr. Fiorentino says. FCX-013 may be an option.

FCX-013 works via genetically modified fibroblasts taken from a patient’s own skin. The skin sample is taken via a standard technique of 3 mm skin punches. Using a lentivirus model, the collected fibroblasts are genetically encoded to hyperproduce matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1), a normal bodily enzyme that functions to break down collagen. FCX-013 is injected at multiple sites under the skin at the location of the excess fibrotic lesion. Actual secretion of MMP-1 secretion is controlled by a compound (veledimex) taken orally by the patient, which then activates expression of MMP-1 via a gene switch. The MMP-1 secreted by the modified fibroblasts then breaks down excess collagen in the sclerotic lesions. When the fibrosis is resolved, the individual stops taking the oral compound, halting the production of MMP-1 by the modified fibroblasts.

Dr. Fiorentino

Dr. Fiorentino explains, “The current strategy using FCX-013 is designed to address the issue of sclerosis—I would imagine the highest potential impact of this therapy would be for morphea lesions on the trunk or extremities that cross over joints [i.e., linear morphea] and cause loss of mobility and joint function.” This is the type of localized scleroderma [morphea] most commonly found in the pediatric population.3

John Maslowski is president and chief executive officer of Fibrocell Science, a cell and gene therapy company in Exton, Pa., that is developing FCX-013. He notes, “If you’ve been following the gene therapy space, a lot of focus has been on blood disorders and, obviously, cancer, because we have some U.S. approvals there; the same for rare retinal diseases. Dermatology is something that is a bit unique and growing now.”

The Study

FCX-013 performed well in safety and efficacy measures in the original proof-of-concept study using immunocompromised mice with fibrotic skin disease. Fibrocell is now initiating a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 clinical trial for FCX-013. The trial plans to enroll 10 patients with moderate to severe localized scleroderma of any subtype, with approximately five patients per phase. The trial’s primary objective is to evaluate the safety of FCX-013. The investigators will also assess the status of the fibrotic lesions and control sites using histology, skin scores and ultrasound, assessing at different time points up to 16 weeks following administration of FCX-013.

Mr. Maslowski notes the first three adult patients will be given FCX-013 in staggered dosing, so the researchers will have a chance to examine safety parameters before starting the next patient on the treatment. “We will collect and submit safety and activity data from the phase 1 adult patients to the FDA and [Data Safety Monitoring Board] for the trial,” he explains. “If the FDA and [Data Safety Monitoring Board] approve our data, they will give us clearance to move into children in the phase 2 portion of the clinical trial. Ultimately, we believe children will benefit from this therapy the most, as the condition can lead to developmental issues.”

For the planned trial, the investigators will use a single injection model, with researchers administering FCX-013 in the same general affected area at a single time point. However, Mr. Maslowski says the FCX-013 injection may theoretically be given more than once, if needed. “We may find over the course of phase 1 that dose escalation is required, as [researchers] may learn in any phase 1 trial.” He also notes the trial has an additional safety mechanism built into the design: The expression of MMP-1 by the fibroblasts can be turned off when the oral compound is stopped.

FCX-013 is the only gene therapy treatment thought to be in clinical development for localized scleroderma. Currently, Fibrocell has no plans to develop FCX-013 for systemic sclerosis. Mr. Maslowski notes that would probably require systemic administration of cells, which entails different toxicity risks compared with a localized approach, such as utilized in the current FCX-013 model.

“We are delighted the FDA has recognized localized scleroderma as a serious disorder,” says Mr. Maslowski. “I think the perception earlier was that the condition was generally cosmetic; however, it really isn’t. We work with the Scleroderma Foundation and other advocacy groups, and I think they are excited to see high-tech interest in this chronic and debilitating disease.”

Dr. Fiorentino concludes, “One thing that will be interesting to follow here is if FCX-013, by decreasing collagen in the skin, is able to have an effect in preventing the end-stage skin tethering and tightness that is characteristic of disabling morphea.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: Clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 Jan–Feb;90(1):62–73.

- Kreuter A. Localized scleroderma. Dermatol Ther. 2012 Mar–Apr;25(2):135–147.

- Torok KS. Pediatric scleroderma: Systemic or localized forms. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012 Apr;59(2):381–405.