Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a systemic autoimmune disease in which immune-mediated inflammation causes secretory gland dysfunction, leading to dryness of the main mucosal surfaces and systemic organ involvement.1 The disease has a difficult-to-pronounce name due to the Swedish ophthalmologist Henrik Sjögren (1899–1986), who described the main disease characteristics in his 1933 doctoral thesis “Zur Kenntnis der keratoconjunctivitis sicca.” The cause of SS is unknown, but genetic and environmental factors seem to play a role. When symptoms appear in a previously healthy person, the disease is classified as primary SS (pSS). When sicca features are found in association with another systemic autoimmune disease, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SSc), or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), it is classified as associated SS; pSS may also be associated with various organ-specific autoimmune diseases.

SS primarily affects white perimenopausal women, with a female:male ratio of nearly 20:1. The disease may occur at all ages, but typically has its onset in the fourth to sixth decades of life. An estimated 2–4 million people in the U.S. have SS, of whom approximately 1 million have an established diagnosis.2 Recent studies using the best-accepted classification criteria (2002 American-European) have estimated a prevalence of one to nine cases per 10,000 people (0.01–0.09%) and an annual incidence of 4.2 cases/100,000 people in the U.S.3 A differentiated clinical and immunological expression has been reported for specific epidemiological subsets (males, pediatric and elderly patients).

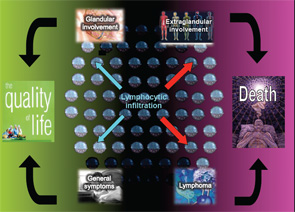

The autoimmune origin of sicca syndrome is often confirmed by positivity for circulating autoantibodies, although some laboratory abnormalities may support the clinical suspicion of pSS, including normocytic anemia, mild leukopenia and, especially, high serum gammaglobulin levels and a markedly raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The variability in the presentation of SS may partially explain delays in diagnosis of up to 10 years from the onset of symptoms. On the one hand, SS is a disease that can be expressed in many guises depending on the specific epidemiological, clinical or immunologic features. On the other hand, SS may be a serious disease with an excess of mortality mainly related to systemic involvement and B-cell lymphoma (see Figure 1). The health costs of SS are significant and similar to those of RA—more than double the cost of non-autoimmune primary care patients.1

Clinical Presentation: More Than Sicca Features

SS may be expressed in many guises, and there are three predominant clinical presentations at onset.1

The triad of dryness, fatigue & pain

A large percentage of patients present with a clinical pattern totally dominated by severe dryness, fatigue and pain, which are not life threatening, but have a serious impact on the quality of life (see Figure 1). Oral and ocular dryness are key to the diagnosis of SS, because they occur in more than 95% of patients, although other sicca symptoms are also frequent, including hoarseness, non-productive cough, cutaneous dryness and dyspareunia in women. In addition to sicca symptoms, generalized pain and/or chronic fatigue are reported in more than 80% of patients with pSS. Physicians should be alert to women reporting dramatic quality-of-life changes due to the abrupt onset of these symptoms. However, a careful assessment is essential in these patients, because this set of symptoms is also characteristic of other processes (e.g., hypothyroidism, neoplasia, primary depression) and, above all, functional somatic syndromes, such as fibromyalgia.1 Greater intensity of dryness, fatigue and pain seems to go in tandem with less systemic involvement and identification of immunological SS features.3

Nonspecific systemic inflammatory syndrome

Some patients, especially children and the young, may present with a clinical pattern characterized by continued, well-tolerated fever, along with night sweats, fatigue, malaise and weight loss. In these patients, the lack of local symptoms and negligible or absent sicca symptoms may delay the diagnosis. However, a history of swelling of the major salivary glands (i.e., parotid and submandibular glands) may be a key feature. Laboratory tests may show normocytic anemia, mild leukopenia and, especially, a very raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate due to high serum gammaglobulin levels. Systemic infections and lymphoma should always be ruled out in these patients.

The occult Sjögren’s syndrome (non-sicca onset)

Some patients with pSS may present with systemic features unrelated to involvement of the mucosal surfaces.3 A large number of non-sicca features may appear before the development of sicca symptoms, including extraglandular manifestations involving the skin, lungs, kidneys or nervous system, together with some laboratory abnormalities, especially cytopenias, which, in some patients, may be symptomatic (e.g., hemolytic anemia, severe thrombocytopenia). Finally, one specific condition, pSS, presents indirectly: a fetal congenital heart block in the fetus of an asymptomatic pregnant woman, which leads to the discovery of underlying maternal anti-Ro antibodies. A significant percentage of these asymptomatic mothers will develop pSS. In all of these patients, a positive immunological result will lead to an early diagnosis of pSS several years before the onset of an overt sicca syndrome and will help prevent systemic complications (e.g., chronic organ damage, lymphoma) by ensuring their timely treatment.

The Importance of Measuring Systemic Disease

Systemic involvement plays a key role in the prognosis of pSS, and three recent studies, including more than 2,500 patients, have confirmed that pSS is a systemic autoimmune disease.4-6 EULAR has recently promoted an international collaboration among more than 40 experts to develop two consensus disease activity indexes in pSS: the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients Reported Index (ESSPRI, a patient-administered questionnaire to assess subjective symptoms) and the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI, a systemic activity index to assess systemic complications). The development of the ESSDAI has represented a step forward in the evaluation of systemic SS and includes specific organ-by-organ definitions that allow the homogeneous evaluation of systemic features in large series of patients.7 Preliminary data presented at the 2014 annual EULAR meeting in Paris showed that those patients with the highest level of activity at diagnosis in at least one domain showed a higher mortality rate, as well as those who were classified as having a high baseline score (ESSDAI >13).8

A large percentage of patients present with a clinical pattern totally dominated by severe dryness, fatigue & pain.

Systemic Sjögren’s May Be Life Threatening

Although severe, life-threatening systemic involvement has rarely been reported in pSS, it may account for nearly 10% of deaths.9 Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis is the life-threatening condition more frequently reported in patients with pSS, with the involvement of vital organs, such as the kidneys, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract. Other severe involvements have been reported, including progressive ataxic neuronopathy, pulmonary arterial hypertension and severe thrombocytopenia or autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

The two internal organs that have the greatest influence on the survival of patients with pSS are the lungs and the kidneys. SS-related pulmonary disease is clearly associated with worsened quality of life and poorer survival, with a two- to four-fold increase in the risk of death compared with patients without pulmonary disease.3 With respect to renal involvement, a recent study, including 35 patients with biopsy-proven renal involvement, found high rates of adverse outcomes, including chronic renal failure (31%), lymphoma (26%) and death (26%), especially in patients with cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephitis.3,10

IgG4-Related Disease, the Great Mimicker

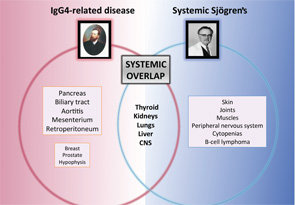

Some systemic diseases may mimic the clinical picture of systemic Sjögren’s through tissue infiltration by granulomas (i.e., sarcoidosis), amyloid proteins (i.e., amyloidosis) or malignant cells (i.e., hematologic neoplasia). However, a new disease was recently added to infiltrative diseases that may mimic systemic Sjögren’s. IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a systemic immune-mediated disease that has been previously described in Japan and is characterized by tissue infiltration of IgG4-bearing plasma cells.11 It is not a new disease, because many previously recognized conditions of unknown etiology and pathogenesis formerly regarded as entirely disparate disorders are now considered to comprise parts of the IgG4-RD spectrum, including Mikulicz disease, Küttner’s tumor and Riedel thyroiditis, among others.

Major salivary glands are among the organs more frequently involved in the IgG4-related disease, reported in 40% of cases.12 Involvement of internal organs is common and may lead to organ failure or severe systemic impairment, particularly in the pancreas, liver and biliary tree, kidneys, thyroid gland, lungs and aorta. A significant number of these organ-specific involvements are common with pSS, including renal, pulmonary, hepatic, thyroid and central nervous system disease (see Figure 2). A specific evaluation for IgG4 disease should be considered for patients with pSS who present with pancreatic signs, renal disease or interstitial pulmonary involvement.

Systemic Therapies: Targeting B Cells

Systemic therapy should be tailored to the organ involved and the severity of the condition, although no controlled trials in pSS guide their use.13 For patients with moderate systemic involvement, including arthritis, non-complicated cutaneous purpura or non-severe peripheral neuropathy, prednisone (<0.5 mg/kg/d) may suffice. For patients with internal organ involvement (e.g., pulmonary alveolitis, glomerulonephritis or severe neurologic features), the traditional therapeutic approach consists of a combination of prednisone and immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide, azathioprine or mycophenolate), especially in patients with associated vasculitic involvement. However, some extraglandular features, such as interstitial nephritis, axonal polyneuropathy or ataxic neuronopathy, seem to have a poor response to corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents.14

Current scientific evidence suggests that B-cell-targeted therapies may be considered in patients with systemic Sjögren’s, especially in those who are refractory to traditional approach (lack of response or intolerance to corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents). The amount and quality of evidence on the off-label use of these drugs (overwhelmingly rituximab) in SS-related extraglandular features is higher than that reported for the use of the standard options (corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents). Several studies have recently evaluated the use of rituximab in pSS patients. Gottenberg et al15 studied the use of rituximab in systemic Sjögren’s and found an overall efficacy of 60%, while Carubbi et al16 found a more-pronounced ESSDAI reduction than in those treated with conventional therapy. In contrast, the efficacy of rituximab in the most prominent triad of symptoms (dryness, fatigue and pain) is not clear.17,18 Because several studies have supported a role for BLyS in the pathogenesis of pSS, inhibiting BLyS may be an attractive therapeutic approach. A recent study found that 18 (60%) out of 30 patients with active pSS who were treated with belimumab showed clinical improvement and significant reduction of the ESSDAI score.19

Not All Patients Require the Same Follow-Up

Patients with disease limited to mucosal surfaces may require only annual evaluation, while those with systemic disease should be evaluated by the specialist in autoimmune diseases at least every six months and those with end-organ damage at least every three months.1 Routine physical examination should include examination for peripheral lymphadenopathy and enlargement of parotid/submandibular glands, the liver and the spleen. Yearly laboratory tests should include full blood count, ESR, and renal and liver function tests. Immunological tests are not necessary in routine follow-up except for markers associated with a poor prognosis (e.g., complement levels, cryoglobulins, monoclonal gammopathy) and in patients with a clinical suspicion of the development of a concomitant systemic autoimmune disease.

Current scientific evidence suggests that B-cell-targeted therapies may be considered in patients with systemic Sjögren’s.

A careful workup in differentiating systemic Sjögren’s from other systemic and autoimmune diseases is mandatory for some specific systemic presentations that are found very infrequently in pSS. These include erosive arthritis, extracutaneous noncryoglobulinemic vasculitis, pericarditis and pleurisy, pancreatitis or proximal renal tubular acidosis, among others. In these patients, specific autoantibodies related to other systemic autoimmune diseases should be provided for the majority of systemic involvements (i.e., negativity will confirm “primary” SS in these patients).

Future Directions

The clinical approach of patients with pSS has traditionally focused on the study and characterization of glandular involvement, even though pSS is undeniably more than a sicca disease. In fact, pSS is still diagnosed (i.e., classified) using criteria exclusively focused on glandular involvement, and this occurs despite the fact that a long list of extraglandular features involving the majority of organs and systems has been reported over the past 30 years. From a practical point of view, diagnostic decision making of systemic Sjögren’s is not standardized and is based on the specific clinical experience of each group—often based on the experience of other diseases, such as lupus or systemic vasculitis—together with expert opinion.

Therefore, the need for a consensus on a homogeneous diagnostic and therapeutic approach to systemic involvement in pSS is clear. The EULAR-SS Task Force Group is now working on the development of EULAR-SS recommendations for the characterization and treatment of organ-specific extraglandular involvement in pSS on the basis of a systematic review of the current scientific evidence. This systematic review revealed a low level of evidence in studies of systemic SS, especially with respect to the diagnostic approach. The body of evidence relied predominantly on information retrieved from individual cases, and the main sources of bias were the heterogeneous definitions of organ involvement—or even the lack of definition in some studies—and the heterogeneous diagnostic approach used in studies to investigate each organ involvement.

A greater understanding of the pathogenesis of systemic immune-mediated damage, along with active international collaborations to develop standardized guidelines, is critical.

Pilar Brito-Zerón, MD, PhD, and Manuel Ramos-Casals, MD, PhD, both work for the Laboratory of Autoimmune Diseases Josep Font, CELLEX, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Department of Autoimmune Diseases, ICMiD, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain.

Members of the EULAR-SS Task Force Steering Group are: Manuel Ramos-Casals, Sjögren Syndrome Research Group (AGAUR), Laboratory of Autoimmune Diseases Josep Font, IDIBAPS, Department of Autoimmune Diseases, ICMiD, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain; Pilar Brito-Zerón, Sjögren Syndrome Research Group (AGAUR), Laboratory of Autoimmune Diseases Josep Font, IDIBAPS, Department of Autoimmune Diseases, ICMiD, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain; Raphaèle Seror, Assistance Publique–Hopitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bicêtre, Department of Rheumatology, INSERM U802, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France; Université Paris-Sud 11; INSERM U1012, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France, and Center of Clinical Epidemiology, Hôpital Hôtel Dieu, Paris, France; INSERM U738, Université Paris-René Descartes, Paris, France; Hendrika Bootsma, Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands; Simon J. Bowman, Rheumatology Department, University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, UK; Thomas Dörner, Rheumatology Department, Charité, University Hospital, Berlin, Germany; Jacques-Eric Gottenberg, Department of Rheumatology, Strasbourg University Hospital, Université de Strasbourg, EA 4438, Strasbourg, France; Xavier Mariette, Assistance Publique–Hopitaux de Paris, Hôpital Bicêtre, Department of Rheumatology, INSERM U802, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France; Université Paris-Sud 11; INSERM U1012, Le Kremlin Bicêtre, France; Elke Theander, Department of Rheumatology, Malmö University Hospital, Lund University, Sweden; Stefano Bombardieri, Rheumatology Unit, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy; Salvatore de Vita, Clinic of Rheumatology, Department of Medical and Biological Sciences, University Hospital Santa Maria della Misericordia, 133100 Udine, Italy; Thomas Mandl, Department of Rheumatology, Malmö University Hospital, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; Wan-Fai Ng, Musculoskeletal Research Group, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK; Aike Kruize, Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Athanasios Tzioufas, Department of Pathophysiology, School of Medicine, University of Athens, Greece; and Claudio Vitali, “Villamarina” Hospital, Department of Internal Medicine and section of Rheumatology, Piombino, Italy, on behalf of the EULAR Sjögren Syndrome Task Force.

Disclosure

Dr. Brito-Zerón is supported by the Josep Font Research Fellow Award, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain.

References

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Sisó-Almirall A, Bosch X. Primary Sjögren syndrome. BMJ. 2012;344:e3821.

- Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan;58(1):15–25.

- Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M. Advances in the understanding and treatment of systemic complications in Sjögren syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014 Jul 19;[Epub ahead of print]. PubMed PMID: 25050925.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Solans R, et al; SS Study Group; Autoimmune Diseases Study Group (GEAS) of the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI). Systemic involvement in primary Sjogren’s syndrome evaluated by the EULAR-SS disease activity index: Analysis of 921 Spanish patients (GEAS-SS Registry). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:321–331.

- Baldini C, Pepe P, Quartuccio L, et al. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome as a multi-organ disease: Impact of the serological profile on the clinical presentation of the disease in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 Dec 24;[Epub ahead of print]. PubMed PMID: 24369420.

- Seror R, Gottenberg JE, Devauchelle-Pensec V, et al. European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index and European League Against Rheumatism Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient-Reported Index: A complete picture of primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1358–1364.

- Seror R, Theander E, Brun JG, et al; on behalf of the EULAR Sjögren’s Task Force. Validation of EULAR primary Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity (ESSDAI) and patient indexes (ESSPRI). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar 11;[Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 24442883.

- Brito Zeron P, Retamozo S, Solans R, et al. The degree of activity measured with the EULAR-SS disease activity index (ESSDAI) strongly correlated with death in patients with primary Sjogren syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(Suppl2).

- Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M, Bove A, et al. Predicting adverse outcomes in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: identification of prognostic factors. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 Aug;46(8):1359–1362.

- Goules AV, Tatouli IP, Moutsopoulos HM, Tzioufas AG. Clinically significant renal involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Clinical presentation and outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2945–2953.

- Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012 Feb 9;366(6):539–551.

- Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M, Stone JH. The clinical spectrum of IgG4-related disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 (in press).

- Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas AG, Stone JH, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome: A systematic review. JAMA. 2010;304:452–460.

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Sisó-Almirall A, et al. Topical and systemic medications for the treatment of primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:399–411.

- Gottenberg JE, Cinquetti G, Larroche C, et al; Club Rhumatismes et Inflammations and the French Society of Rheumatology. Efficacy of rituximab in systemic manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: Results in 78 patients of the AutoImmune and Rituximab registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1026–1031.

- Carubbi F, Cipriani P, Marrelli A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in early primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A prospective, multi-center, follow-up study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R172.

- St Clair EW, Levesque MC, Prak ET, et al; Autoimmunity Centers of Excellence. Rituximab therapy for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: An open-label clinical trial and mechanistic analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1097–1106.

- Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren syndrome with rituximab: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Feb 18;160(4). doi: 10.7326/M13-1085.

- Mariette X, Seror R, Quartuccio L, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: Results of the BELISS open-label phase II study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Dec 17;[Epub ahead of print]. PubMed PMID: 24347569.