BOSTON—The latest research on the pathophysiology and treatment of small- and large-vessel vasculitides was presented by three international experts at a clinical symposium called “Therapeutic Decisions in Systemic Vasculitis” at the ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting in Boston last November. Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, of the rheumatic and immunologic disease department at the Cleveland Clinic, and Carol Langford, MD, MHS, director of the Center for Vasculitis Care and Research at the Cleveland Clinic, discussed treatment options for small-vessel vasculitides. Paul Bacon, MD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Birmingham (U.K.), discussed large-vessel vasculitis.

For Treatment, Severity is Key

“The most important message,” for practitioners, said Dr. Villa-Forte, is that the treatment approach should be “decided according to the severity of clinical manifestations” and the rate of change of disease progression.

Vasculitides are a diverse group of diseases the result from inflammation of the arteries, veins, capillaries, or other blood vessels. Depending on the extent and duration of vessel involvement, vasculitis can be very serious because it ultimately impedes blood flow to vital organ systems. It affects patients of all ages, can be chronic or acute, and often flares up after long periods of remission.

Each year, only about 500 Americans are diagnosed with Wegener’s granulomatosis—a type of small-vessel vasculitis that eventually causes damage to the lungs and kidneys. The same low incidence is true for large-vessel vasculitis, like Takayasu’s arteritis. Not surprisingly, practicing rheumatologists may not have extensive experience with the management of this family of diseases, and treatment options have been limited.

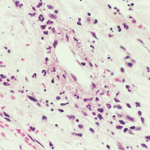

Vasculitic disease can be difficult to diagnose because they share symptoms—like fatigue, abdominal pain, hypertension, renal insufficiency, and neurologic dysfunction—with many other diseases. A firm diagnosis usually requires a tissue biopsy of one of the organs that has been affected.

Small- and Medium-Vessel Vasculitides

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides are among the most common forms of vasculitis. Until recently, the standard treatment of ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis was cyclophosphamide (CYC) and prednisolone. However, both of these drugs can have series side effects.

“The initial protocols for CYC came with high rates of infection, bone marrow suppression and other prolonged types of toxicity,” said Dr. Villa-Forte. Since then, combination therapy of CYC, prednisolone, and methotrexate (MTX) “has made a marked impact on the treatment of the disease. Otherwise it would be mostly fatal.”

The first study to directly compare CYC and MTX was conducted by nephrologist Kirsten de Groot and colleagues at the Hannover Medical School in Germany in 2005 (Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2237-2242). The 100-patient study found that, at six months, the remission rate in patients treated with MTX was 89.8%, just slightly less than the 93.5% remission rate of patients treated with CYC. At the same time, 34% of patients treated with MTX experienced adverse events, while 74% of CYC patients experienced adverse events.

The MTX regimen was not as effective in patients with extensive disease, however, and was associated with more relapses than CYC after the initial treatment period. Also, Dr. Villa-Forte noted, patients whose vasculitis involved the kidney should not be given MTX because it accumulates in patients with renal insufficiency. “I don’t think we have enough data to support that [MTX] should be started as a first-line agent” for patients with extensive disease, said Dr. Villa-Forte. Instead, practitioners “should always be thinking of a staged therapy,” she said. Her two-step approach for patients with severe disease is to first begin treatment for a short period with CYC, and then switch to a less toxic treatment like MTX for maintenance treatment. For mild to moderate disease, she advised treatment with MTX alone.

Dr. Villa-Forte has evidence for the efficacy of two-step staged approach because of her experience with 82 Wegener granulomatosis patients over 12 years, with a 4.5-year follow-up. As published in Medicine in September 2007 (86(5):269-277), patients on the staged treatment all improved. Fifty percent of patients achieved remission within six months and 72% within a year. Sustained remission was ultimately achieved in 78% of patients. However, relapse rates were high. Of the 75 patients who had any kind of remission, 45% relapsed within a year and 66% within two years. “No matter which current standard therapy we decide to use, we still have high relapse rates. We need to better understand the physiology of this disease,” she said.

Dr. Langford agreed: “In reality there’s very little data focused specifically on the issue of relapse. Ultimately, when we face how to manage, a lot comes down to what’s best for our individual patient. A lot comes down to opinion.”

Large-Vessel Vasculitides

When Dr. Bacon discussed Takayasu’s arteritis, a vasculitis disease that affects the aorta, one of the first things he stressed was that it “is not in any sense a sister disease to the small vessel vasculitides” that were discussed by Drs. Villa-Forte and Langford. “And that’s important when you try to extrapolate treatment,” he continued. “This clinical course is different and the pathology is different.”

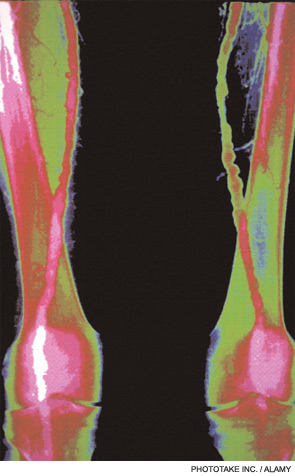

Patients with Takayasu’s arteritis will generally complain of symptoms related to reduced blood flow in the upper neck and head, he said. Takayasu’s arteritis is sometimes referred to as “pulseless disease” because it’s difficult to take the pulse of many patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Unlike the small-vessel vasculitides previously described, Takayasu’s arteritis has a nine-to-one ratio of females to males. It usually occurs in women under 40, and is more common among Asians.

Takayasu’s arteritis is like the other vasculitides, though, in that it is very uncommon—Dr. Bacon said there is only one case per million population in the U.K.—and in that its extremely challenging to diagnose. The inflammation can exist for many years, producing mild or non-specific symptoms, arthralgia or mylalgias until there is a evidence of serious vascular insufficiency such as claudication, angina or a major complication, such as stroke; aortic regurgitation may also occur because of valve involvement. The vast majority of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis are treated with prednisone.

Dr. Bacon discussed various factors to look for when diagnosing Takayasu’s arteritis. “The major factor, unfortunately, is pulse loss,” he said, though the disease can be detected using other tests before it progresses that far. Angiograms, which show narrowing or occlusion of the blood vessels, are currently the standard diagnostic test. But an angiogram “doesn’t tell you anything about what’s going on in the blood vessel wall, so it can’t distinguish disease activity from scars and is therefore a poor guide to therapy,” he explained. Recent studies have shown that advanced MRI can show wall thickening both in the aorta and in all the major arterial segments. “Therefore, this is a clear advance in assessing the degree of activity of the disease,” he said.

Virginia Hughes is a medical writer based in New York City.