WASHINGTON, D.C.–Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is associated with a number of rheumatic diseases, and patients may be referred by pulmonologists to rheumatologists for management. Patients with one of these conditions, especially when associated with connective tissue diseases, often have poor prognoses. Diagnosis can be challenging, and there are still few effective therapies for many of these conditions.

A panel of experts on connective tissue–associated ILD spoke at a session titled, “Connective Tissue Disease–Associated Interstitial Lung Disease,” at the 2012 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held here November 9–14. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect.] They offered some insight on diagnosing and treating these patients, as well as a glimpse into areas of research that may be promising.

ILD is a group of conditions associated with many connective-tissue diseases, said Aryeh Fischer, MD, acting chief of the division of rheumatology at National Jewish Health in Denver. These conditions typically are marked by interstitial inflammation and/or fibrosis of the lungs. Symptoms are not always clear, but imaging, histopathologic, and function tests may provide the best clues for diagnosis, he said.

Serious and More Mild ILDs

One of the most serious connective tissue–associated ILDs is usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), an idiopathic condition marked by a honeycombing pattern seen on radiographs and fibrosis, Dr. Fischer said. UIP is most commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and is also commonly seen in scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. It has the worst prognosis in this classification, Dr. Fischer noted.

Another commonly seen ILD in rheumatic diseases is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, a condition with a better prognosis than UIP. Prognosis for survival can depend on factors like the patient’s age, smoking status, and familial history, Dr. Fischer noted. Patients with RA may also develop bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, an inflammation of the bronchioles with a comparatively good prognosis for recovery. Other conditions that may be seen in rheumatic disease patients include lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and, more rarely, severe acute interstitial pneumonia.

Where ILD Is Most Common

ILD is most commonly found in systemic sclerosis at a prevalence rate of 25% to 90%, Dr. Fischer said. It is also found less frequently in polymyositis and dermatomyositis, RA, Sjögren’s syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus. If rheumatologists are treating patients with known connective tissue disease, they should take steps to determine if possible ILD is connective tissue disease¬ associated, Dr. Fischer said. Recognition of the exact disease would affect treatment decisions and the prognosis for these patients. “It’s important for the patients’ outcome to see where they fit,” he said.

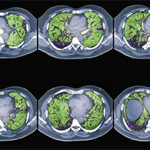

Diagnosis typically involves assessing pulmonary function and examining high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans. Bronchoscopy also may be a useful diagnostic tool, along with bronchoalveolar lavage to assess for infection and alveolar hemorrhage, Dr. Fischer said. Transbronchial biopsy may not add much useful information, he added.

It’s important for pulmonologists to get rheumatologists involved in diagnosis and treatment for these patients, Dr. Fischer said. ILD has a “rheumatologic flavor,” he said, with some patients presenting with specific autoantibodies and histopathologic features. With connective tissue–associated ILD, however, there often is a lack of extrathoracic features, he said.

How should these conditions be treated? For ILD in systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD), the rheumatologist must first ask whom to treat, when to treat, and what therapy to try, said Richard Silver, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Severity of SSc-ILD is greater in African Americans, males, and patients over age 70, Dr. Silver said. Risk factors include patients who are positive for the Scl-70 or U11/U12 RNP antibody and patients with severe esophageal disease, he said. “We have to look at patients phenotypically, seriologically, and, in the future, genotypically as well, to identify patients who are at the highest risk” of developing ILD, he added.

In the future, rheumatologists may be able to identify who is at higher risk for ILD and target those people for more aggressive therapy, Dr. Silver said. Serum biomarkers for SSc-ILD include SP-D and KL-6. Patients who had both SSc and alveolitis by bronchoalveolar lavage or ground glass on HRCT chest scan had higher serum levels of both SP-D and KL-6, a potentially prognostic factor in the decline of lung function in these patients, he added.

Targeting Treatment

When should rheumatologists observe and wait to treat patients, and when should they intervene immediately? HRCT results showing the extent of ground glass opacity and forced vital capacity (FVC) levels are two key determinants, Dr. Silver noted. For example, if FVC is greater than or equal to 70% predicted, it may be best to observe and delay treatment. If FVC is less than 70% and lung function is declining, treatment may be warranted.

Cyclophosphamide is an effective treatment, but toxicity concerns make long-term use problematic, Dr. Silver said. Other treatments now in clinical trials are mycophenolate mofetil, imatinib mesylate, and rituximab. In the future, treatments like immunosuppressive therapy, antifibrotic therapy, or cell-based therapy with hematopoietic or mesenchymal stem cells may help these patients, he said. Biomarker research may soon offer more useful clues for treatment options, Dr. Silver said. “At this point, it is the art and not the science of medications,” he concluded.

Treatment decisions may be complicated further by comorbidities like pulmonary hypertension, a condition that can lead to heart failure, said Stephen Mathai, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. Pulmonary hypertension commonly complicates connective tissue–associated ILD, he said. The condition is related to multiple etiologies and must be assessed and treated on a case-by-case basis.

Incidence of pulmonary hypertension in ILD is difficult to assess, but some tests provide clues. Systemic sclerosis-ILD-PH is defined with a right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) measurement greater than 35 mm Hg. In patients with RA-ILD-PH, the RVSP is greater than 30 mm Hg. In both sets of patients, it is important to look at both pulmonary function and imaging results, Dr. Mathai said. However, an estimate of RVSP is only possible in 54% of patients with ILD, he added. Other tests to help diagnose pulmonary hypertension include echocardiogram, diffusing capacity (DLCO), and FVC/DLCO.

“Pulmonary hypertension is a bad prognostic indicator in many pulmonary conditions, and ILD is no exception,” said Dr. Mathai. Comorbidities need to be addressed in these patients, including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, pulmonary embolism, and coronary artery disease, which is common. Obstructive sleep apnea may be seen, prompting treatment with an end-tidal or transcutaneous carbon dioxide monitor. Atrial arrhythmias are very poorly tolerated in pulmonary hypertension patients, he said.

Goals of treatment include improving functional capacity and quality of life as well as survival, Dr. Mathai said. If there is a reduction of oxygen content in the alveoli, constriction may lead to a worsening of oxygenation, he added. Current therapies include vasodilators, including oxygen therapy for patients with chronic hypoxemia; diuretics for patients with volume overload; and digoxin for patients who need to increase cardiac output.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.