The quantification of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in osteoarthritis (OA) plays a key role in determining the severity and outcome of OA. This issue is of key importance to rheumatologists as the population ages and the number of patients with OA dramatically increases. In both research and practice, the evaluation of the therapeutic benefit of interventions—used either alone or in combination—is critical. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness are essential attributes of health status measurement tools, while brevity, simplicity, and ease of scoring are regarded with high importance, particularly in clinical practice applications.1

Prior to 1981, measurement procedures for quantifying pain, stiffness, and physical disability in hip and knee OA studies lacked standardization. In 1982, with the encouragement of the late Watson Buchanan, MD, who was clinical professor of rheumatology at the University of McMaster in Hamilton, Canada, I described the development of a health status questionnaire termed the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) in the course of completing an MSc thesis in clinical epidemiology and biostatistics.2 The WOMAC was conceptualized and an item inventory was proposed between 1981 and 1982; the index was validated and implemented between 1982 and 1999.3,4 The original index has undergone significant refinement and there is now a broad range of WOMAC tools to meet different measurement needs.

In comparative analysis against performance-based measurement techniques, the WOMAC has frequently been superior in performance.

A Version for Every Need

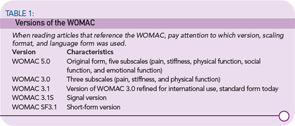

The WOMAC contains five pain, two stiffness, and 17 physical function items, and is available in five-point Likert (LK), 100-mm visual analogue (VA), and 11-point numerical rating (NR) scaling formats.5 The majority of the validation work has been conducted with the LK and VA formats, although the NRS version has also been studied. There are approximately 1,500 citations (full manuscripts, abstracts, reviews) in the literature to use of the WOMAC. The WOMAC LK3.1 and WOMAC VA3.1 versions, in particular, have been extensively used, especially for assessing efficacy in clinical research environments and, increasingly, in clinical practice. (See Table 1, p. 19, for more on versions of the WOMAC.)

These are some of the features that have made the WOMAC a widely used tool:

- Extensive patient involvement in the item inventory development, which reduced the potential influence of paternalism and anchored it to aspects of the disease experience that are relevant to OA patients;

- Numerous studies that have evaluated clinimetric properties of the index (e.g., validity, reliability, and responsiveness) and issues such LK versus VA scaling and blind versus informed presentation;3-5

- Development and validation of more than 70 alternate-language forms of WOMAC VA3.1 and WOMAC LK3.1;

- Continual research and development into content and administration issues, including the application of WOMAC in telephone interviews and electronic data capture formats; 5

- Recognition by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials group (OMERACT), Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), and the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials group, and regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency, among others;6,7

- Provision of the WOMAC, in the required scaling format, alternate language form, and administration format, for academic, industrial, clinical, and educational applications, including pivotal projects and programs such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Osteoarthritis Initiative; and

- Ongoing user support, to provide the most appropriate form of the index to meet specific user needs.

Transcultural adaptation of WOMAC 3.1, in particular, has been a complex process spearheaded by the Health Outcomes Group in San Francisco, Calif. The impact of environmental challenges involved in, for example, stair climbing and transportation, are different in different parts of the world, and bathing and toileting habits also vary, but the WOMAC appears capable of tapping into global commonalities that exist in OA symptoms.

Validation

In comparative analyses against performance-based measurement techniques, the WOMAC has frequently been superior in performance. Likewise, in comparisons against other disease-specific measures the WOMAC has compared favorably, and against generic health status measures has often been superior in responsiveness.5

Traditionally, OA clinical trial data are analyzed at the group level. Recently, attention has focused on individual patient-reported outcomes. These can be considered in two general forms: responder criteria, in which each patient is classified as a responder or nonresponder to treatment, based on whether their change in health status exceeds a predefined threshold; and state-attainment criteria, in which patients are classified on the basis of when, whether, and/or for how long they achieve a certain predefined level of low symptom severity.

WOMAC data have contributed significantly to the development of both response and state attainment criteria. (Download a list of WOMAC’s contributions to clinical criteria at www.The-Rheumatologist.org under “Download Issues.”)

Patient Participation, Focus Key

Patient involvement in estimating the clinical importance of improvement, and the acceptability of different levels of symptom severity is innovative, and meets the requirements for consumer involvement in decision making. The process also helps establish consumer-based definitions for response and state attainment in knee and hip OA.

An alternative method of benchmarking patients’ health status is against normative values derived from WOMAC items and estimated from a survey of the general population. The first such survey targeting 24,000 members of the general public has been completed, and data from a second survey, targeting a further 36,000 members, are currently being analyzed.8 Once completed, age- and gender-specific normative values based on items in the WOMAC NRS3.1 should be specified from about 7,500 subjects for pain and stiffness and about 13,000 subjects for physical function.

The International Classification of Function (ICF) proposed by World Health Organization provides a conceptual framework for health status assessment. An ICF core set has been described for OA, and the WOMAC successfully mapped to the ICF framework.9,10 A model has been developed for predicting utility scores that closely approximate those derived by direct measurement, which has important implications for health economic analyses.11

Collaboration Continues

The WOMAC also paved the way for rapid development of a comparable index for hand OA studies, termed the Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN 3.1) Hand Osteoarthritis Index.12 Like the WOMAC, the AUSCAN index is a tridimensional, self-completed, patient-centered health status questionnaire, encompassing pain, stiffness, and physical function.13 The AUSCAN Index contains five pain, one stiffness, and nine physical function items and has been validated in both five-point LK and 100-mm VA scaling formats; an 11-point NRS version is also available. The AUSCAN Index has been translated into 32 alternate-language versions, and is recognized in OARSI Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials in hand OA. The concepts of OMERACT-OARSI Responder Criteria, AUSCAN 20-50-70 Responder Criteria, and BLISS (Pain) Index have recently been explored in hand OA patients, and appear applicable.14 For more information, visit www.auscan.org or www.womac.org.

The last 25 years of WOMAC development have involved an extensive collaboration, as well as the commitment of patients with knee and/or hip OA. In addition to providing a standardized tool for evaluating treatment response, WOMAC data have also been important in informing decisions regarding the proposal of response criteria and state-attainment criteria, as well as AUSCAN. The WOMAC and AUSCAN indices are well placed to meet current and emerging OA needs in clinical research and practice. Given the availability of response criteria (OMERACT-OARSI, MCII75, MPCI, WOMAC 20-50-70), state-attainment criteria (PASS75, BLISS), and population-based normative data, the opportunities for incorporating quantitative measurements into routine clinical practice are great and will hopefully improve outcomes.

Dr. Bellamy is professor and director of the Centre of National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine and faculty of health sciences at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia.

References

- Bellamy N, Kaloni S, Pope J, Coulter K, Campbell J. Quantitative rheumatology: A survey of outcome measurement procedures in routine rheumatology outpatient practice in Canada. J Rheumatol. 1998; 25: 852-858.

- Bellamy N. Osteoarthritis—an evaluative index for clinical trials [MSc thesis]. McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; 1982.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt L. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. J Orthopaedic Rheumatol. 1988; 1: 95-108.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt L. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988; 15: 1833-1840.

- Bellamy N. WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index User Guide. Version VIII. Brisbane, Australia; 2007.

- Osteoarthritis Research Society (OARS) Task Force Report. Design and conduct of clinical trials of patients with osteoarthritis: recommendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. Osteoarthritis Cart. 1996; 4: 217-243.

- Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT Recommendations. Pain. 2003; 106: 337-345.

- Bellamy N, Wilson C, Hendrikz J. Community-based normative values for disability derived from WOMAC and AUSCAN NRS 3.1 indices. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(Suppl II):491.

- Dreinhöfer K, Stucki G, et al. ICF core sets for osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2004; Suppl. 44: 75-80.

- Weigl M, Cieza A, Harder M, Geyh S. Linking osteoarthritis-specific health-status measures to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003; 11: 519-523.

- Grootendorst P, Marshall D, Pericak D, et al. A model to estimate Health Utilities Index Mark 3 utility scores from WOMAC index scores in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):534-542.

- Bellamy N, Campbell J, Haraoui B, et al. Clinimetric properties of the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index: an evaluation of reliability, validity and responsiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002; 10: 863-869.

- Bellamy N. AUSCAN Hand Osteoarthritis Index User Guide III. Brisbane, Australia 2006.

- Kvein T, Zhang Y-Z, Nichols M, et al. Response and state-attainment criteria in hand OA: Analyses from a placebo-controlled clinical trial of CRx-102, a novel synergistic combination therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007; 66(Suppl II):501.