It is now well established that disease-modifying drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate (especially if used at higher weekly doses) or leflunomide, can significantly improve clinical and functional outcomes in RA and retard joint damage. This therapeutic success is limited because absence of active disease is rarely achieved. With the advent of biological agents, we have witnessed responsiveness in patients who were refractory to more traditional therapeutic measures. In addition, we learned that beyond increasing the proportion of responding patients it is possible to increase the magnitude of the response because many patients in clinical trials and clinical practice achieve a state of very low disease activity. Some even show no evidence of active disease.

More than a decade ago, response criteria were developed to allow for assessment of improvement of disease activity in the course of therapeutic interventions, particularly in clinical trials.1 These ACR response criteria call for a categorical minimal proportional improvement of disease activity from baseline rather than for the achievement of a categorical disease activity state. In fact, the discontinuous nature of the criteria, in conjunction with the variability of the baseline activity, does not allow for the determination of actual disease activity.

For clinical practice, however, criteria that allow evaluating actual disease activity may be more valuable for a variety of reasons. (See “Why We Need Disease Activity Criteria,” bottom right).

History of Assessment

The Disease Activity Score (DAS) and the 28-joint DAS (DAS28) were the first tools to provide a continuous disease activity measure for RA.7,8 The subsequently developed European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria employed numerical changes of the DAS or DAS28 in combination with the achievement of a particular categorical disease activity state to determine a moderate or good response.9 This was an important step beyond assessment of mere disease activity improvement. Nevertheless, even patients with a good response are usually afflicted with residual disease activity, and even a response that leads to remission may only be called moderate if the numerical improvement criterion for a good response is not fulfilled.

With the use of biological therapies, the evaluation of response has reached a new dimension. Even patients who are non-responders by the traditional measures can have a virtual arrest of joint damage progression on a group level when treated with a TNF-inhibitor in combination with methotrexate, providing evidence for a dissociation of the inflammatory response with the destructive events by such therapy.10 Even with TNF-blocker combination therapy, radiographic changes progress more in high disease activity states than low disease activity states.11

Why We Need Disease Activity Criteria

1) Disease activity, regardless of the means of its assessment, spans a wide range, which is easier to appreciate if translated accordingly, such as into an activity thermometer;

2) Many agents—particularly the biologics—are indicated for patients with “active” RA, but the term “active” is not well defined (Moderately active? Very active? Very, very active?);

3) Entry criteria for clinical trials require a minimal number of swollen and tender joints (usually at least six to 10), but in clinical practice most patients do not fulfill entry criteria for clinical trials, although these patients suffer from their disease and its progression; and

4) It has been shown in both randomized controlled clinical trials and observational studies that continued active disease—irrespective of the definition of the term “active”—translates into longitudinal progression of joint damage and irreversible functional impairment.2-6

Why Strive for Remission?

It is well established that disease activity, as measured by acute phase response levels or swollen joint counts over time, correlates with progression of joint destruction.3,4,6,12 We have also learned that individual measures of disease activity do not constitute the most valid and reliable instruments.13,14 As a result, composite indices are preferable because they capture several aspects of disease and translate and combine them into a single score that accounts for the inherent variability of disease between and within the individual patient. Composite disease activity indices, such as the DAS28, the simplified disease activity index (SDAI) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) have been increasingly used in clinical trials and practice over the years. (See Table 1) These indices allow for categorization of disease activity as high, moderate, low, and remission by virtue of their scales. While it may seem apparent that a long-term state of high disease activity when compared with a long-term state of remission will lead to different disease outcomes, it is less clear that low disease activity would be associated with a worse outcome than remission, although this is the case.

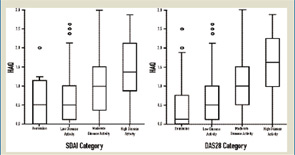

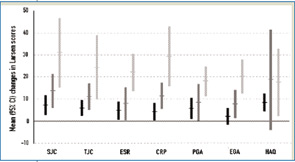

The cross-sectional data depicted in Figure 1reveal that median Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores are quite different when comparing patients at low disease activity with those in remission.15 The long-term analyses shown in Figure 2reveal that low disease activity over time allows for more progression of joint damage than remission over time, and that this is true irrespective of the measure applied.16 If we wish to halt progression of joint damage and achieve maximal reversal of functional impairment, we need to aim for remission. Although there is a possibility that—even in remission—individual patients have some mild progression of joint damage, this is not the case for the vast majority.17 Thus, the lowest degree of disease activity—remission—is the best we can currently aim for to obtain an optimal functional and structural outcome and, therefore, the most desirable state for our patients.

Source: Rheumatology. 2006;45:1133-1139.

When one strives for remission, one is aiming to achieve a disease a state (or disease activity category) rather than a mere proportional improvement. This means that patients with high disease activity have to experience larger changes than patients with moderate or low disease activity. Remission is associated with a much smaller reduction of inflammatory load in patients with moderate disease activity than patients with high disease activity. Striving for remission requires rethinking our attitude toward therapeutic goals and standards.

But how do we best measure remission?

Criteria for Remission

Remission may be defined on the basis of individual categorical terms or composite indices. The ACR remission criteria call for the fulfillment of five of six requirements.18 (See Table 1, right.) In the modified ACR criteria, fatigue has been omitted, and four of the five remaining characteristics need to be present to accomplish remission.19 The ACR criteria allow for any of the individual variables—including joint counts—to have highly abnormal values as long as the other five (or four) have normalized.20

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires not only fulfillment of the ACR criteria but also evidence of arrest of radiographic changes and for clinical remission to be present for more than six months.21 These criteria combine clinical and structural remission, which may not be the initial therapeutic aim for rheumatologists and, by using the ACR criteria for clinical remission (“five-of-six” requirement), may also be misleading in some cases.

Therefore, defining remission by composite scores may be more valuable in clinical practice and possibly also in clinical trials. Categories for remission have been clearly defined for the DAS28, SDAI, and CDAI. 9,15 (See Table 1, at right.) The SDAI and CDAI remission criteria (≤3.3 and ≤2.8)—by virtue of their subcomponents—do not allow for the presence of more than one tender and one swollen, or two tender or two swollen joints. In fact, the vast majority of the patients in SDAI or CDAI remission have no tender or swollen joint.20

DAS28 remission differs somewhat from SDAI and CDAI remission. Up to 16 swollen joints (or up to eight tender joints) can be present in DAS28 remission (<2.6), and one or more residual swollen joints can be found in 25% or more of the patients.15,20,22-25 The DAS28 remission state may mean low disease activity or a state near remission for a large proportion of patients, leaving room for potential treatment increase given current therapeutic aims. Considering that a majority of rheumatologists would not consider more than one swollen and/or two tender joints acceptable for defining remission, trial reports of up to 40% of patients in remission represent an exaggeration of the term remission, since the DAS28 was used in these definitions.4,26-28 While this difference may appear semantic, it may, in fact, be meaningful as depicted in Figure 1 (see p. 16) where one can see a subtle difference in residual HAQ levels between DAS28 and SDAI remission, which comprises the medians and the 75th percentiles.

Defining remission is especially important if reduction of a therapeutic modality is being considered; this decision may be made differently in a patient with no (or at best one residual) swollen or tender joints when compared, for example, to a patient with five or more residual active joints. In defining remission it is important to consider the scores used, their components, and their construction to avoid potential treatment withdrawal in patients with residual activity. In our clinic, we usually aim therapy toward remission and employ the CDAI criteria, which makes immediate decisions possible and does not require waiting for any laboratory test. C-reactive protein levels can be used for confirmatory purposes or to calculate the SDAI.

Sustained Remission

Even if you achieve remission at one point in time, you should not feel satisfied with the treatment outcome. Yo-yo effects, where a state of remission is followed by states of low to even high disease activity, are common.29 The goal should be sustained remission, achievable in a considerable number of patients in clinical practice with today’s therapies (up to 20%, even when using stringent SDAI/CDAI criteria), a tremendous advance over previous decades.20

Consider Patient and Physician Perspectives

Several studies show that physicians evaluate swollen joint counts more stringently than tender joint counts or pain, while the reverse is true when patients assess their disease.4,22,30,31 This can be seen by the differences observed when comparing patients’ and physicians’ global assessments of disease activity, which are often disparate.4,22,32 On the other hand, variables primarily valued by patients (such as tender joints) relate to different outcomes than those mostly valued by physicians (such as swollen joints): Tender joint counts in the short and long term correlate best with functional impairment, while swollen joint counts over time are predominantly associated with increasing joint damage.3 Consequently, judging the disease state as “very good” by virtue of the absence of pain and tender joints would translate into a propensity for joint destruction in residual swollen joints. On the other hand, judging the disease state as “very good” due to the absence of swollen joints—despite the presence of residual tender joints—would neglect the respective functional consequences.

Among the various continuous disease activity indices, only the SDAI and the CDAI capture all four components: tender and swollen joints as well as physicians’ and patients’ global assessments of disease activity. Moreover, both joint counts (i.e., tender and swollen) have equal weights as do both global assessments. Variables important to the patients and physicians are considered with similar weight in these scores, and the ease in calculating these indices allows doctors and patients to speak the same language. In fact, in our clinics, we educate patients to “know the DAI.”

Make Remission the Goal

Less than a decade ago we would not have considered using the term “remission” but in exceptional circumstances rarely occurring in patients cared for by rheumatologists. With today’s treatment approaches achieving remission has become a reality for a considerable proportion of patients. Further, as new treatments and more innovative therapies are developed, this aim will be far more reachable.

Getting patients into remission and sustaining remission requires consistent follow-up using individual measures of disease activity and composite scores. Only if we measure the characteristics of the disease consistently can we be sure that we will capture subtle changes of disease activity that may require therapeutic modifications.33,34 This proximity of changes in clinical status and the rheumatologist’s response to these changes is one of the major achievements of rheumatology practice. A variety of sensitive and well-validated tools are available to track disease progression, with these tools providing a platform to promote remission as the goal of care for all patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Smolen is professor of medicine and chair of the division of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria and chair of the second department of medicine at the Center for Rheumatic Diseases at Hietzing Hospital in Vienna. Dr. Aletaha is a fellow in rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna.

References

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:727-735.

- Sokka T, Pincus T. Most patients receiving routine clinical care for rheumatoid arthritis in 2001 did not meet inclusion criteria for most recent clinical trials or American College of Rheumatology remission criteria. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1138-1146.

- van Leeuwen MA, Van der Heijde DM, van Rijswijk MH, et al. Interrelationship of outcome measures and process variables in early rheumatoid arthritis. A comparison of radiologic damage, physical disability, joint counts, and acute phase reactants. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(3):425-429.

- Aletaha D, Machold KP, Nell VPK, Smolen JS. The perception of rheumatoid arthritis core set measures by rheumatologists. Results of a survey. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1133-1139.

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS, Ward MM. Measuring function in rheumatoid arthritis: identifying reversible and irreversible components. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2784-2792.

- Welsing PM, van Gestel AM, Swinkels HL, Kiemeney LA, van Riel PL. The relationship between disease activity, joint destruction, and functional capacity over the course of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):2009-2017.

- Prevoo MLL, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van de Putte LBA, van Riel PLCM. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44-48.

- Van der Heijde DMFM, van’t Hof M, van Riel PL, van de Putte LBA. Development of a disease activity score based on judgement in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:579-581.

- Van Gestel AM, Prevoo MLL, van’t Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LBA, van Riel PLCM. Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:34-40.

- Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde D, et al. Infliximab inhibits radiographic progression regardless of disease activity at baseline and following treatment in patients with early active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (Suppl), (in press).

- Smolen JS, van der Heijde DMFM, St.Clair EW, et al. Predictors of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate without or with concomitant infliximab. Results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:702-710.

- Drossaers-Bakker KW, de Buck M, van Zeben D, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. Long-term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1854-1860.

- Goldsmith CH, Boers M, Bombardier C, Tugwell P. Criteria for clinically important changes in outcomes: development, scoring and evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis patients and trial profiles. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:561-565.

- van der Heijde DM, Van’t Hof MA, van Riel PL, van Leeuwen MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB. Validity of single variables and composite indices for measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:177-181.

- Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, Nell VPK, Stamm T, Smolen JS. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: Defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2625-2636.

- Aletaha D, Machold K, Nell VPK, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid arthritis core set measures and perception by rheumatologists. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52 (Suppl).

- Molenaar ET, Voskuyl AE, Dijkmans BA. Functional disability in relation to radiological damage and disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission. J Rheumatol. 2002 Feb;29(2):267-270.

- Pinals RS, Masi AT, Larsen RA. Preliminary criteria for clinical remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24(10):1308-1315.

- Prevoo ML, van Gestel AM, van THM, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Nov;35(11):1101-1105.

- Mierau M, Schoels M, Gonda G, Fuchs J, Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2007 (in press).

- Food and Drug Administration. Clinical development programs for drugs, devices and biological products for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. US Department of Health and Human Services, Feb 1999. Available at www.fda.gov/cber/gdlns/rheumcln.pdf. Last accessed February 21, 2007.

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Remission of rheumatoid arthritis: should we care about definitions? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(6 Suppl 43):S045-S051.

- Makinen H, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Sokka T. Is DAS28 an appropriate tool to assess remission in rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1410-1413.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D. What should be our treatment goal in rheumatoid arthritis today? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(6 Suppl 43):S007-S013.

- van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Boers M, et al. Comparison of different definitions to classify remission and sustained remission: 1 year TEMPO results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1582-1587.

- Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study—A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:26-37.

- Maini RN, Taylor PC, Szechinski J, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, tocilizumab, in European patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had an incomplete response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug 31;54(9):2817-2829.

- St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3432-4343.

- Mierau M, Gonda G, Pezawas L, et al. Defining remission in rheumatoid arthritis using different instruments. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(Suppl):239.

- Wolfe F, Cathey MA. The assessment and prediction of functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1298-1306.

- Heiberg T, Kvien TK. Preferences for improved health examined in 1,024 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: pain has highest priority. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Aug;47(4):391-397.

- Antoni CE, Maini R, Grunke M, Gefeller O, Stalgis C, Smolen J, et al. Cooperative on quality of life in rheumatic diseases: results of a survey among 6000 patients across 11 European countries. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46 (Suppl 1): Abstract 98.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, De Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3381-3390.

- Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:263-269.