Teaching junior learners, such as medical students and residents, is increasingly important in rheumatology. Given the anticipated shortage of rheumatologists, attracting more trainees to our field and enhancing knowledge of the rheumatic diseases among physicians in other fields are critical to meeting the needs of our patients.1,2

Teaching junior learners, such as medical students and residents, is increasingly important in rheumatology. Given the anticipated shortage of rheumatologists, attracting more trainees to our field and enhancing knowledge of the rheumatic diseases among physicians in other fields are critical to meeting the needs of our patients.1,2

In addition, clinical reasoning is a vital skill for junior learners, but as medical student and resident autonomy has decreased over time, so may have the opportunity to practice clinical reasoning. Rheumatology is an optimal setting for the deliberate practice of clinical reasoning, and rheumatologists are in a particularly strong position to teach it.

Working with junior trainees poses many challenges. Few medical students and residents pursue careers in rheumatology, which may create the perception of less robust learner engagement. Junior learners tend to be less familiar with rheumatology than they are with medical subspecialties that receive more exposure.

Moreover, time and space are significant barriers to effective teaching, particularly in the outpatient setting. Junior learners may take more time than a fellow to independently assess a patient and often require more preceptor time with the patient to provide effective care. In addition, faculty working with junior learners may not have multiple exam rooms to enable trainees to see patients independently.

In this article, we present frameworks and tools to use in teaching junior learners. These are organized into three phases (i.e., pre-patient encounter, encounter and post-encounter). We discuss the importance of the learning contract in the pre-encounter phase, using active teaching techniques during the visit and feedback and asynchronous learning following the encounter.

Before the Encounter

Principles of adult learning theory (ALT) provide a helpful framework for effective teaching (see Table 1).3 ALT posits that adults learn best in situations relevant to their current work or anticipated career, situations that build on their prior experiences and situations in which learning is problem centered and practical. The pre-encounter period, which includes the beginning of the learner’s rotation, as well as the time before each clinic session, is critical to setting the stage for teaching in the ALT framework and to the development of a relationship between preceptor and learner.

Studies have demonstrated that today’s learners value relationships with their teachers and that effectiveness of feedback is dependent in part on the relationship between the student and preceptor.4,5 An understanding of the learner’s interests and background gives the preceptor the ability to connect subsequent learning points to the learner’s interests or to draw parallels with topics they already know well. Making these connections is a valuable educational strategy, but it also reinforces relationship building with the learner.

A key step in the pre-encounter period is the development of a learning contract between learner and preceptor, wherein goals, roles and logistics of the rotation or clinical encounter are agreed upon. Asking the learner what they would like to learn and how they learn most effectively helps set expectations for both parties and brings structure to an experience that can otherwise be plagued by uncertainty for the learner. Importantly, the learning contract should include the expectation that the learner will have an active role in the clinical experience—the specifics will likely vary with each learner and clinical scenario and are discussed in more detail below.

Table 1: Adult Learning Theory

| Key Tenets | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Adults are self-directed | Learners enjoy the opportunity to manage their own learning and practice independence | • Develop a learning contract • Enable learner autonomy and decision making |

| Adults are internally motivated and benefit from a readiness to learn | Adults want to learn concepts that are relevant to their current work or anticipated career | • Define a role for the learner during the patient encounter • Focus on aspects of the case that are relevant to the learner’s future career • Teach clinical reasoning |

| Adult learning is impacted by their previous experiences | Adults can apply their experience to new learning | • Inquire about prior experiences • Help learners link new learning to prior experiences |

| Adults have a problem-based orientation | Adults enjoy learning that is problem-centered and practical | • Prioritize teaching points, highlighting those most relevant to the patient encounter or the learner’s goals |

A preceptor’s thorough knowledge of a patient’s case before the encounter can pay dividends in terms of control and efficiency during the encounter. This allows the preceptor to guide the learner as needed during the encounter and can inform brief, pre-encounter teaching points (e.g., anatomy review, approach to joint pain).

Asking the learner to review a topic before the start of a clinic session can help shift teaching time outside the clinical encounter. This provides the preceptor with valuable insight into a learner’s zone of proximal development (the conceptual space between what a learner can do independently and what they can do with assistance), which can then guide the preceptor’s educational efforts during the encounter. Pre-teaching also encourages immediate practical application of theoretical knowledge and sets learners up for success, which naturally builds enthusiasm for the subject.

During the Encounter

Perhaps the most important aspect of teaching during a patient encounter is the maintenance of learner engagement and active learning. In the traditional setup in which a learner evaluates the patient independently and then presents to the preceptor, we often use the One-Minute Preceptor (OMP) model to guide the teaching encounter (see Table 2), although a number of other frameworks have been proposed.6

Although it is tempting to evaluate the learner’s knowledge based on their presentation alone, getting a commitment and probing for supportive evidence can help more precisely identify knowledge gaps and direct time-efficient teaching. Identifying the knowledge gap or zone of proximal development through clarifying questions is critical to making teaching effective and time efficient. After all, the goal is not for preceptors to teach but for learners to learn.

Table 2: One-Minute Preceptor Model

| Steps | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Get a commitment to a diagnosis or differential diagnosis | Getting a commitment makes the teaching more engaging and personal. It draws on the ALT tenet of optimized learning in situations that are problem-based. | “You’ve nicely summarized the case of an 81-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis presenting with acute monoarthritis. What are your leading considerations in this case?” |

| Probe for supporting evidence | This step helps the preceptor understand the thought process behind the answer in the first step and gives insight into their knowledge and clinical reasoning. | “What elements make you think gout is most likely?” “What do you think about the possibility of septic arthritis?” |

| Reinforce what was done well | Positive reinforcement increases the likelihood that the learner will repeat positive skills/behaviors (which they may not have recognized themselves) in future encounters. It also helps create a positive learning environment. | “Your hypothesis-driven physical exam was excellent and helped prioritize the differential diagnosis.” |

| Give guidance on errors and omissions | Identification of errors and omissions provides important opportunities for targeted education. | “Her lack of fever does not have a high negative predictive value for septic arthritis, which is an important consideration because of its associated morbidity/mortality—your plan for an arthrocentesis will help us further evaluate for this possibility.” |

| Teach a general principle | Junior learners are not rheumatologists, so it is especially important to connect clinical encounters to more broadly applicable principles. | “It is common in rheumatology and other specialties that work with immunosuppressed patients to encounter a patient whose use of immunosuppressive medications both predisposes them to infection and makes their presentation with infection more subtle.” |

When time is particularly short, preceptors can teach effectively simply by thinking out loud about the case. Further, some teaching can be aimed at both the patient and the learner at the same time to increase efficiency. As discussed earlier, we try to increase relevance of the teaching by linking it to the learner’s anticipated specialty, aspects that are applicable to all specialties (e.g., clinical reasoning) or other, broader learning objectives (e.g., knowledge important for the shelf exam).

Junior learners in subspecialty settings often shadow their preceptors. The main limitation of shadowing is the passive role the learner often assumes, which does not take advantage of ALT principles. However, shadowing can be an effective learning modality when the trainee assumes the role of an active learner. We use the term active apprenticeship when describing this model.

We try to achieve learner engagement in the active apprenticeship model through three steps.7 First, we engage the learner by familiarizing them with the patient and making learning relevant. This can be done by asking the learner to read about the patient before the encounter or giving them a brief patient history, often accompanied by a question to further enhance engagement and promote critical thinking (e.g., “This 36-year-old woman presented with eight weeks of pain, swelling and morning stiffness in the wrists, metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints and knees without other symptoms. What laboratory tests would you order?”). We often simplify the case description depending on the learner level and our teaching objectives.

Second, when time allows, we ask the learner to perform a part of the history or physical exam. This presents an important opportunity to observe the learner in a time-efficient manner, which subsequently enables the preceptor to provide specific feedback. While observing, the preceptor can write the visit note. Alternatively, asking the learner several questions that pertain to the patient history or exam, or teaching briefly during the visit, can also be considered.

Third, and most important, we set the expectation that at the end of the encounter we will discuss the learner’s opinion about the diagnosis or management decisions encountered in the visit. In our experience, this expectation is crucial to maintaining learner engagement even if the learner does not take an active role in the visit itself. We typically step out of the exam room to discuss the learner’s thoughts to limit the hesitation they may have in sharing their thoughts in front of the patient. We then use elements of the OMP model to structure the discussion. We have found that although these discussions take only a few minutes, they have a significant positive impact on learning and engagement.

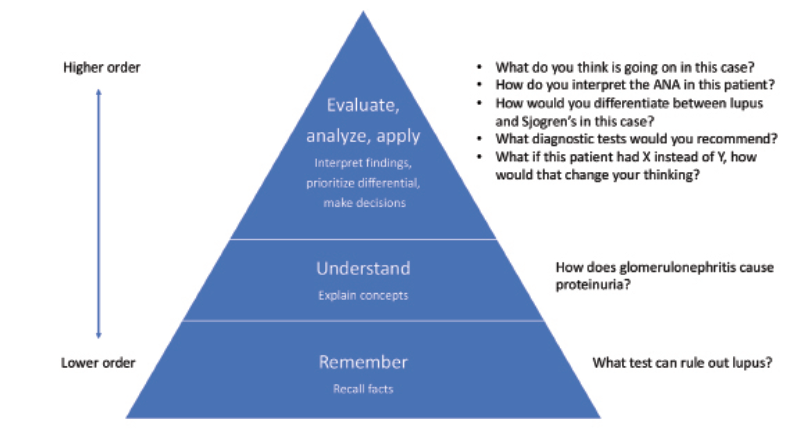

It should be noted that the type of questions used in teaching affects their impact. Using higher order questions according to Bloom’s Taxonomy framework (see Table 3) is most effective at identifying knowledge and reasoning gaps and fostering student engagement.8,9 Finally, junior learners have much to learn and it can be tempting to teach many concepts in an encounter. Our general goal is to teach fewer concepts but to do so in an active manner while staying on time and moving additional teaching to the pre- or post-encounter periods.

After the Encounter

The post-encounter period is an important time to extend the educational opportunities provided by the patient evaluation. Shared experience and direct observation of learners allow the preceptor to provide more specific feedback, which ideally highlights what the learner should continue to do as well as areas for improvement.10,11 The latter can then serve as focus points for continued learning in the post-encounter period, either by providing a resource to review or asking the learner to look something up that can be revisited at a future time.

Including the learner in post-encounter communications with other members of the care team requires little additional time, but we have found it can make the learner feel like a valued part of the team while also exposing them to multidisciplinary care.

In Sum

Precepting junior learners is a challenging but important task. The pre-, during and post-encounter framework described here can help organize an approach to

teaching junior learners and help maintain timely delivery of effective patient care in clinical practice. Developing a learning contract is critical to successful teaching during patient encounters. Using active teaching techniques, such as the OMP, can enhance learning and knowledge retention.

Fostering learner engagement through the active apprenticeship model can improve the traditional shadowing experience. Specific feedback and directing asynchronous learning in the pre- and post-encounter period can extend learning beyond the visit. Using aspects of these techniques has the potential to foster transformational learning experiences, which can help our learners and our patients.

Ian Cooley is a second-year rheumatology fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. His clinical and research interests include crystalline arthritis, musculoskeletal ultrasound and medical education.

Eli M. Miloslavsky, MD, is an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Disclosures

Dr. Cooley is an editorial contributor to Practice Update, Rheumatology (Elsevier); and a contributing editor to Clinical Reasoning (NEJM Group).

References

- Battafarano DF, Ditmyer M, Bolster MB, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Workforce Study: Supply and demand projections of adult rheumatology workforce, 2015–2030. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Apr;70(4):617–626.

- Miloslavsky EM, Bolster MB. Addressing the rheumatology workforce shortage: A multifaceted approach. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020 Aug;50(4):791–796.

- Knowles MS. The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Rev. and updated. Cambridge, The Adult Education Company. 1980.

- Roberts DH, Newman LR, Schwartzstein RM. Twelve tips for facilitating Millennials’ learning. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):274–278.

- Ramani S, Könings KD, Ginsburg S, van Der Vleuten CPM. Relationships as the backbone of feedback: Exploring preceptor and resident perceptions of their behaviors during feedback conversations. Acad Med. 2020 Jul;95(7):1073–1081.

- Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. Jul-Aug1992;5(4):419–424.

- Restrepo D, Hunt D, Miloslavsky E. Transforming traditional shadowing: Engaging millennial learners through the active apprenticeship. Clin Teach. 2020 Feb;17(1):31–35.

- Anderson, LW, Krathwohl, DR. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman. 2001.

- Hausmann JS, Schwartzstein RM. Using questions to enhance rheumatology education. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Oct;71(10):1304–1309.

- Kritek PA. Strategies for effective feedback. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015 Apr;12(4):557–560.

- Bing-You R, Hayes V, Varaklis K, et al. Feedback for learners in medical education: What is known? A scoping review. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1346–1354.