In 1998, my friends Gary Firestein, MD, chief of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and Wim van den Berg, PhD, head of the rheumatology research lab and professor of experimental rheumatology at Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences in The Netherlands, and I edited a book called “T Cells in Arthritis.”1 In the introduction, we wrote that “The goal of this book is to outline the major arguments and data suggesting that T cells may, or may not, be central players in the pathogenesis of chronic [rheumatoid arthritis (RA)]. … a great deal is at stake when considering these important questions. Most significant, the direction of future therapeutic interventions depends heavily on how one interprets the pathogenesis of RA.”

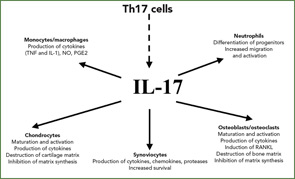

Indeed, today T cells are back, and we already act on T-cell interactions in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with CTLA4-Ig (Orencia), which inhibits T-cell costimulation by blocking the interactions of CD28 on T cells and B-7 molecules on antigen-presenting cells. This paper will focus on novel cytokine interleukin-17 (IL-17), a central player in immune regulation, and the related Th17 cells. In contrast to the more classical reviews on IL-17, I will provide here a more personal description of how these molecules and concepts have emerged to be so fashionable today.2

The Saga of T Cell–Derived Cytokines

Every rheumatologist knows that the RA synovium is highly infiltrated by T cells. A way to link T cells with RA pathogenesis would be the demonstration of the production of T cell cytokines by the RA synovium. In 1987, Dr. Firestein, however, showed in rheumatoid synovium the lack or very low levels of interferon-γ (IFNγ), then considered together with IL-2, as the most characteristic Tcell–derived cytokine.3 From these results, he asked, “How important are T cells in arthritis?”4

The next cytokine evaluated was IL-4, another T cell–derived cytokine critical for immunoglobulin E (IgE) production. Using the first available IL-4 ELISA, we showed in 1990 the RA joint lacks IL-4.5 Since IL-4 also has anti-inflammatory and anti-destructive effects, the lack of IL-4 in RA could explain how chronicity of an inflammatory disease would lead to destruction. Arguments against the role of T cells also came from the lack of efficacy of anti-CD4 antibodies in treating RA. Various explanations were offered for how so many T cells could accumulate in the synovium without having a role in disease.

The Discovery of IL-17

Once IL-17 arrived on the scene in 1995, its link with RA was immediately established. One of the first reports describing the role of the cytokine IL-17 showed that synoviocytes from RA patients produced IL-6 when exposed to IL-17. This established the first link between IL-17 and inflammation.6