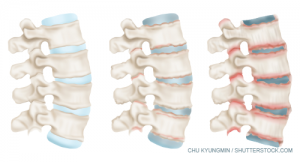

Normal and inflamed human vertebral

column joints in ankylosing spondylitis.

Sir William Osler, widely regarded as one of the greatest physicians of the 20th century, once said, “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.”1 This sentiment is particularly true in the field of rheumatology, in which understanding the patient’s experience with their disease is perhaps even more important than rote memorization of the facts concerning the disease itself. This attitude and the need for objective measures of disease activity have led to the development of broadly accessible and easy-to-use patient-reported outcomes in many of the rheumatic diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis.

2 Important Self-Administered Instruments

In 1994, researchers in the United Kingdom published work describing two important self-administered instruments used to track the natural history and response to treatment in ankylosing spondylitis patients: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI).2,3 Both of these tools were developed using multidisciplinary teams of health professionals and by receiving direct input from patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

The BASDAI includes six visual analog scales used to measure the severity of fatigue, spinal and peripheral joint pain, localized tenderness and morning stiffness, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and the goal of this instrument is to measure disease activity, disease progression and prognosis in a reproducible and dependable manner.

Although this questionnaire measures symptoms of pain and stiffness, Andrei Calin, MD, FRCP, consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, U.K., and colleagues noted that what is not well captured by these questions alone is a patient’s level of function in daily life. Thus, the effort was made to develop a set of questions to examine the degree of difficulty a patient has performing activities related to functional anatomic limitations and to evaluate the patient’s ability to cope with everyday life, leading to the BASFI questionnaire (see Figure 1, below).

A Patient’s Perspective

Since these landmark publications, the BASDAI and BASFI have been used in many research studies and, increasingly, are employed in tracking disease status and progression by rheumatologists in the clinic. However, the question remains, how do patients feel about the use of such a functional index? To answer this question, we spoke with Gary Hitch, a senior noncommissioned officer in the U.S. Army who was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis 17 years ago.

Ankylosing spondylitis commonly affects the joints between the spinal bones and the sacroiliac joints.

Dominique Duval/Science Source

The initial diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis did not come quickly or easily; indeed, as a young adult, Mr. Hitch, had experienced several years of back pain that frequently necessitated use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, with only mild relief of his symptoms. More than one doctor suggested these symptoms were due to “growing pains,” and he was also told that he may have fibromyalgia. It was his dogged determination—the same willpower that allowed him to succeed in the military despite the significant physical symptoms he was experiencing—that prompted him to continue to search for answers regarding the etiology of his back pain. When he was eventually found to be HLA-B27 positive and to have evidence of sacroiliitis with erosive disease on imaging, it became clear which organic process was contributing to his functional limitations.

Mr. Hitch notes that he has been asked the BASFI questions multiple times in the past, mostly when working with physical therapists in the treatment of his ankylosing spondylitis [see Figure 1 below]. He explains that certain questions are quite helpful in getting at the heart of the daily activities that are affected by symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis, such as putting on socks, bending forward from the waist to pick up objects on the ground, and reaching up to place an item on a high shelf. Other questions are not included in the BASFI that many patients with ankylosing spondylitis would clearly relate to, such as questions about limitations in bathing (i.e., getting in and out of a tub, washing one’s body in the shower and needing to adapt one’s hygiene routine based on limitations posed by symptoms).

Mr. Hitch also notes that many patients with ankylosing spondylitis would likely understand the conundrum posed by physical activity, for example. He explains that physical activity in moderation often helps his symptoms, but that too much activity or performing the same activity for too long will exacerbate his pain. Thus, he indicates that it would be helpful if patient-reported outcomes included a time parameter and measured how long a patient can perform an activity before being limited by pain or other symptoms.

Increasing Public Awareness

In addition to one’s own experience with a disease, Mr. Hitch points out that hearing from other patients can be helpful and bring attention to conditions that would otherwise be neglected in typical conversations in the lay press or at work. For example, he cites Mick Mars, the guitarist for the rock band Mötley Crüe, as a celebrity who has spoken quite publicly and repeatedly about his diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis and what it means to persevere in a demanding music career despite the symptoms that he experiences.

Mr. Hitch explains that with increasing public awareness of ankylosing spondylitis, fewer cases of this diagnosis will be missed, and individuals who have patiently treated their back, neck or hip pain conservatively can be further evaluated by a rheumatologist. Indeed, recognizing that HLA-B27 is inherited in a Mendelian fashion and recalling that his father has experienced back pain for many years, Mr. Hitch urged his father to seek evaluation, leading to a correct diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, just like his son.

Mr. Hitch states that the same strong will that allows many patients with chronic back pain to move on with life despite significant symptoms can sometimes cause reticence with regard to seeking an in-depth evaluation and treatment with a rheumatologist. “The mindset of a lot of people with ankylosing spondylitis is fighting the good fight,” Mr. Hitch said. “For my father, his back pain was starting to result in depression, and I pulled him aside and explained that I inherited risk factors for this condition and that, at worst, he could undergo some blood tests and imaging to see if this diagnosis applied to him as well. It was not a hard conversation to have, but one that we had to have many times.”

The field of rheumatology would do well to imitate Mr. Hitch in his relentless pursuit of the truth, and perhaps then the patient-reported outcomes by which we measure disease activity will best reflect the true experience of the patients that we hope to help and serve as an even more useful tool in the treatment of disease. As Mr. Hitch notes, “Doctors learn a lot about a lot, but patients can give them the knowledge and experience they seek to help them and others. In turn, patients should give their trust and faith to their doctor, share their views with them, and listen to all options.”

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his MD. He is currently in practice with Arthritis, Rheumatic, & Back Disease Associates, New Jersey.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, completed his fellowship in rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, where he also earned his MD. He is currently in practice with Arthritis, Rheumatic, & Back Disease Associates, New Jersey.

References

- The four founding physicians. Johns Hopkins Medicine website. http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/history/history5.html.

- Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol.1994 Dec;21(12):2286–2291.

- Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: The development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994 Dec;21(12):2281–2285.

| Figure 1: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) | ||

| Rate the following on a scale of 0–10, with 0 being “easy” and 10 being “impossible”: | ||

| 1 | Putting on your socks or tights without help or aids (e.g., sock aids)? | |

| 2 | Bending forward from the waist to pick up a pen from the floor without an aid? | |

| 3 | Reaching up to a high shelf without help or aids (e.g., helping hand)? | |

| 4 | Getting up from an armless chair without using your hands or any other help? | |

| 5 | Getting up off the floor without any help from lying on your back? | |

| 6 | Standing unsupported for 10 minutes without discomfort? | |

| 7 | Climbing 12–15 steps without using a handrail or walking aid (one foot on each step)? | |

| 8 | Looking over your shoulder without turning your body? | |

| 9 | Doing physically demanding activities (e.g., physiotherapy exercises, gardening or sports)? | |

| 10 | Doing a full day of activities whether at home or work? | |

| Functional ability: The mean of the individual scores is calculated to give the overall index score. Scores on the BASFI of 6/10 suggest high levels of functional limitation. | ||