Figure A. Flexion contractures of bilateral elbows, as well as Boutonniere and swan neck deformities of the fingers in a patient with 25 years of untreated seropositive rheumatoid arthritis

Through the development of a multidisciplinary musculoskeletal institute, we have created a model that facilitates coordination of care of complex patients between medical and surgical subspecialists, physical therapists, dieticians and social workers. A case is presented to demonstrate the improved care experience for both patients and providers and to share our learnings more broadly.

The Case

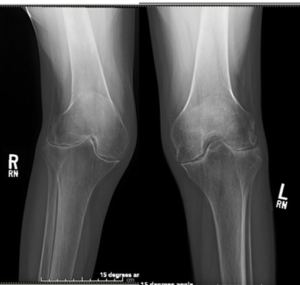

Ms. K. sat in a wheelchair, wearing a large straw hat with a sunflower pasted to the brim and a smile the same size. Her daughter sat by her side, seven months pregnant. I introduced myself and shook her hand, taking care not to squeeze too tightly. As she told me about herself, I observed. Flexion contractures of both elbows, and Boutonnière and swan neck deformities of several fingers were present (see Figure A). She had profound bony hypertrophy of the knee joints with flexion contractures (see Figure B). I searched for a cane propped up in a corner but did not find one.

Ms. K. was 54 years old. She moved to Texas from Liberia to live with her daughter. Joint pain and swelling had developed 25 years earlier. Her symptoms were attributed to sickle cell trait, and pain was managed with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. When she arrived in Austin, she qualifirf for the Medical Access Program, a local health coverage program that helps uninsured, low-income residents gain access to select health services. She was diagnosed with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis by her new primary care provider and referred to our rheumatology clinic.

Figure B. Bilateral knee contractures with bony hypertrophy, rendering the patient unable to extend her legs past 45º.

“How long have you been using that wheelchair?” I asked.

“About one-and-a-half years.”

“Why did you start using it?”

“My knees … they don’t go straight. It hurts to stand.”

“Are you able to stand on your own, or walk at all?”

“I can stand up with some help. I can walk a couple steps. But then I have to stop. The pain is just too much.”

She was able to laterally transfer herself to the exam table without assistance. Knees were contracted by 45º bilaterally. Audible crepitus and synovitis were present. Quadriceps strength was normal with minimal muscle atrophy.

We chatted about rheumatoid arthritis, medical therapies and treatment goals. She had never seen an orthopedic surgeon before, but would be interested in joint replacement surgery if I thought it would help. “I’ll find out,” I said.

That afternoon, I emailed my new surgical colleague, Karl Koenig, MD. I had just accepted a position as the first rheumatologist in the Musculoskeletal Institute at UT Health Austin, becoming part of a multidisciplinary team comprising several integrated practice units dedicated to different musculoskeletal conditions. I gave him a quick rundown:

Figure C. Bilateral symmetric joint space loss, erosions and periarticular osteopenia of the knee joints consistent with rheumatoid arthritis.

“Ms. K. is in her 50s, otherwise healthy. She has had severe, untreated, erosive rheumatoid arthritis for over 25 years. She is wheelchair bound due to knee pain and contracture but her strength is preserved. Radiographic images are available for your review (see Figure C). I have never seen deformities of this degree and am not sure if surgery is even an option. What do you think?”

He emailed me back within five minutes:

“I’m your man. Complex joints are my specialty. Send her my way.”

The patient was scheduled to see him the following week.

Six weeks later, Ms. K. underwent bilateral total knee arthroplasty. As arthroplasty cases go, this one was challenging. Due to her disease and inactivity, she had 45º flexion contractures and severe disuse osteopenia. Simultaneous bilateral surgery was required because a patient cannot walk with one straight leg and the other at 45º. However, we worked with her on prehabilitation and prepared her home environment ahead of surgery with our team of physical therapists and social workers to ensure she was set up for success.

To improve the delivery of musculoskeletal care, we had to go back to the drawing board & build a system around the conditions we are treating from the perspective of the patient.

Karl and I remained in close communication both pre- and postoperatively. Preoperatively, methotrexate was continued as per the 2017 ACR/American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Guideline for the Perioperative Management of Antirheumatic Medication in Patients with Rheumatic Diseases Undergoing Elective Total Hip or Total Knee Arthroplasty.1 Corticosteroids and biologic therapies were deferred until after surgical recovery to minimize the risk of infection or poor wound healing. Shortly post-op, Karl sent me a video of Ms. K. in the rehabilitation gym. She was doing leg presses with near-complete extension of both her knees. A few months later, she walked into my clinic for her follow-up appointment.

The Goal

Patients, payers, providers and policymakers have expressed a need for novel care delivery models designed around patient-centered value and are actively pursuing payment structures to encourage this approach in musculoskeletal care. Why? Because the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions represents a very large portion of the total healthcare spending in the U.S. In fact, the report of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative in 2018 showed that adults reported to have a chronic musculoskeletal condition accounted for an estimated $332 billion in healthcare spending from 2012–2014.2

Unfortunately, when considered as a whole, musculoskeletal care is delivered by an enormously fragmented system—primary care providers, urgent care facilities, emergency departments, chiropractors, podiatrists, physical therapists, rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons, just to name a few. All of them are working in their own separate silos with their own specific toolboxes, disparate success metrics, and absolutely no incentive to communicate with one another. In reality, they are usually competing among themselves in some form. It is no wonder that patients get bounced around, over-imaged and overmedicated. Their overall health is rarely addressed. The system is simply not built to do that particular job.

When analyzed with respect to value (defined as health benefits that accrue to patients per healthcare dollar spent), most current models of practice fall short due to: 1) an inability to measure outcomes that truly matter to patients, 2) limited transparency around the clinical and financial outcomes that are measured, and 3) a lack of care coordination across providers involved in the patient’s musculoskeletal care cycle.3

To improve the delivery of musculoskeletal care, we had to go back to the drawing board and build a system around the conditions we are treating from the perspective of the patient. Multidisciplinary teams with co-location and built-in coordination through a shared incentive structure and measurement platform can and do vastly decrease the waste in the system. This is the basic concept of an Integrated Practice Unit (IPU) and is the cornerstone of a new paradigm in care delivery. When multiple related IPUs are coalesced into institutes—like the Musculoskeletal Institute at UT Health Austin—the silos break down and coordination of care is directly enhanced across conditions.

The Execution

The first step toward building a successful musculoskeletal care delivery system is creating a structure upon which to divide the most important symptoms, conditions or patient segments (i.e., creating IPUs). This can be a challenge because being too inclusive in a single IPU will dilute the team’s ability to provide focused, high-value care for that condition, and picking conditions that are too rare or narrow makes it difficult to justify the upfront investment in resources.

A base condition should have a high prevalence, burden of disease and cost of care across the patient population to maximize the opportunity for value improvement. In our institute, we created multidisciplinary teams dedicated to chronic conditions of upper extremity, lower extremity, back/neck and inflammatory/autoimmune disease (i.e., arms, legs, backs or all of those). These buckets are designed from the patient’s perspective and understanding rather than specific medical diagnoses to make it easier for them to be placed with the appropriate team.

We then created the multidisciplinary team that would be held accountable for managing the condition. The team included clinical and non-clinical members: orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, physiatrists, advanced practice providers, social workers, registered dieticians, physical therapists, chiropractors, registered nurses and medical assistants.

It is becoming more common for orthopedic surgeons and rheumatologists to co-locate in outpatient group practice settings, although this remains a somewhat new concept. The Integrative Rheumatology and Orthopedics Center at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, is one such model that exemplifies perioperative co-management of patients by rheumatologists and orthopedists.4 The center has several research projects underway, focusing on such topics as perioperative flares in rheumatoid arthritis.5 However, outcomes data for this collaborative approach is wanting and needed.

Conclusion

In a climate in which the medical and surgical worlds often remain separate and mired by long referral waitlists, we have intentionally broken down traditional silos by bringing rheumatology, physiatry and orthopedics together into a single clinical entity. From the provider perspective, it is a pleasure to work in an environment where interactions between medical and surgical providers are not only expedient, but collegial.

In more traditional settings, the co-management of patients like Ms. K. meant long hold times attempting to contact providers, unreturned pages and endless games of phone tag. Clinic notes with plans of care were often faxed to the wrong place, or not at all. Coordination of care was so challenging as to be nonexistent.

At the Musculoskeletal Institute at UT Health Austin, perioperative communication is easy, timely and enjoyable. We safely manage medications and transitions of care via face-to-face interactions or secure electronic communication. We provide the help of physical therapists and social workers to address patients’ social and financial challenges before and after surgery. In short, we provide patient-centered care.

Ms. K. was extremely grateful to both me and Dr. Koenig for allowing her to walk again. Our team is proud of what she achieved, and with joy in our hearts, we have all watched the video of her doing leg presses just weeks after surgery.

We entered this profession to be good doctors who provide great care to patients regardless of the circumstances. This case demonstrates what can happen when we put good doctors into a system that it is built to foster frequent and true collaboration. In reality, intelligent design deserves more credit for her success than her care team. Isn’t it time to start designing our care teams around the success of the patient from the patient’s perspective?

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine at in the Division of Rheumatology at Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin. Her interests include clinical education and patient care. She is an active member of the ACR Insurance Subcommittee.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine at in the Division of Rheumatology at Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin. Her interests include clinical education and patient care. She is an active member of the ACR Insurance Subcommittee.

Karl Koenig, MD, MS, FAOA, FAAOS, FAAHKS, is chief of the Division of Orthopedic Surgery at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin and the medical director of the UT Health Austin Musculoskeletal Institute.

Karl Koenig, MD, MS, FAOA, FAAOS, FAAHKS, is chief of the Division of Orthopedic Surgery at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin and the medical director of the UT Health Austin Musculoskeletal Institute.

Key Takeaways

- Integrated practice units that include both rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons facilitate and expedite the perioperative care of patients with inflammatory arthritides.

- Healthcare systems can be specifically designed and built to foster multidisciplinary care and collaboration at the individual patient level.

- More programs of this type should be designed, implemented and measured to demonstrate a path forward in providing real-world, value-based care to our patients.

References

- Goodman SM, Springer B, Guyatt G, et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology/American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons guideline for the perioperative management of antirheumatic medication in patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing elective total hip or total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Aug;69(8):1111–1124.

- BMUS: The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States: Prevalence, societal and economic cost.

- Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 23;363(26):2477–2481.

- Integrative Rheumatology and Orthopedics Center.

- Goodman SM, Bykerk VP, DiCarlo E, et al. Flares in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after total hip and total knee arthroplasty: Rates, characteristics, and risk factors. J Rheumatol. 2018 May;45(5):604–611.