Based on the classification system developed by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis is defined as a necrotizing vasculitis involving small vessels that is associated with myeloperoxidase (MPO) ANCA or proteinase 3 (PR3) ANCA and displays minimal immune deposits. The mechanism behind the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis is not fully understood.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a subset of ANCA-associated vasculitis defined as a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis involving small and medium vessels, which is commonly associated with glomerulonephritis. Ocular vasculitis and pulmonary capillary inflammation with hemorrhage are also seen in GPA, and a limited form of GPA with ANCA positivity and manifestations only in the respiratory tract is also possible.1

GPA is more common in the Caucasian population with ancestry from northern Europe than in other populations and has a peak incidence between ages of 60 and 70 years. Numerous infectious, environmental and pharmacologic triggers for GPA exist, and the presentation of patients with GPA can vary a lot.2

Clinical manifestations of GPA vary widely and may include constitutional symptoms (fever, weight loss, myalgia, arthralgia), ocular involvement (scleritis, retinal vasculitis), ear, nose and throat involvement (sinusitis, nasal ulcers), respiratory tract involvement (cough, shortness of breath, alveolar hemorrhage, lung infiltrates, lung nodules, tracheal lesions), renal involvement (glomerulonephritis, proteinuria, hematuria, renal failure), nervous system involvement (headache, peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, cerebral vascular lesions, meningitis) or cutaneous lesions (purpura, subcutaneous nodules, ulcerations).3 Cardiac involvement, less frequent than other organ system involvement, can manifest as pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis or coronary vascular disease.4

The diagnosis of GPA is based on the patient’s clinical presentation and supporting laboratory and histologic findings. However, no well-established diagnostic rules or criteria exist. A positive ANCA is not required to diagnose GPA, and diseases that present similarly to a small vessel vasculitis must be excluded.

Infective endocarditis can present similarly to small vessel vasculitis. Clinical findings of fever, weight loss, myalgia and arthralgia, pulmonary infiltrates, glomerulonephritis and purpuric rash can be seen in both conditions. Many laboratory findings are seen in both conditions as well, such as elevated inflammatory markers, low complements and the presence of autoantibodies. In particular, ANCA, which is regarded as a very specific marker for vasculitis, can be positive in infective endocarditis as well.

In a recent prospective study of 109 patients with infective endocarditis, 18% had a positive ANCA on immunofluorescence testing (cytoplasmic [C-ANCA] or perinuclear [P-ANCA]) and 8% had a positive ANCA on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing (PR3-ANCA or MPO-ANCA). In addition, 35% had a positive rheumatoid factor test, 16% had a positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test and 23% was positive for anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Younger age, echocardiographic vegetations and elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels were associated with a positive C- or P-ANCA.5

In addition to small vessel vasculitis and infective endocarditis, ANCA testing can also be positive in inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, malignancies and as a reaction to certain pharmaceuticals.6 Therefore, it can be incredibly difficult to distinguish between an infective endocarditis with a positive ANCA and an ANCA-associated vasculitis with endocardial involvement.

We describe the case of an elderly woman who presented with historical, physical, laboratory and echocardiographic findings consistent with infective endocarditis, including a vegetation on the mitral valve, who was ultimately determined to have GPA and managed with immunosuppressive therapy.

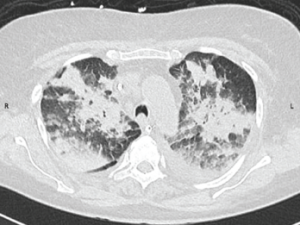

Figure 1: CT Scan of the Chest

A CT scan of the chest obtained without intravenous contrast demonstrates diffuse patchy and groundglass opacifications with upper lobe predominance. These findings are consistent with pulmonary hemorrhage. In addition, bilateral pleural effusions are seen.

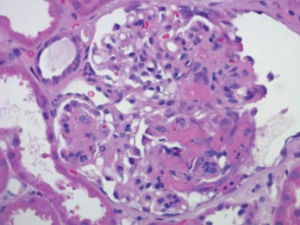

Figure 2: Renal Biopsy

Biopsy specimen of the kidney stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrates a necrotizing glomerulonephritis with a fibrinous crescent within the glomerulus. Immune-complex deposits were not seen on electron microscopy (image not shown).

Case Report

A 78-year-old Caucasian woman presented to an outside hospital with a one-week history of shortness of breath and diffuse joint pains in her bilateral knees and shoulders. Her medical history included hypertension not controlled by any medications, an appendectomy, multiple family members with rheumatoid arthritis and a five pack-year smoking history. She did not take any medications at home. Three weeks prior to presentation, she underwent a tooth extraction for a dental abscess and was given a course of penicillin.

On presentation, she was afebrile with a blood pressure of 195/85 mmHg and a heart rate of 150 beats per minute. Further examination demonstrated a III/VI systolic murmur heard across the precordium. A petechial rash was present on the right lower extremity, and splinter hemorrhages and Osler nodes were present on the fingers of both hands. Her laboratory studies were notable for a total leukocyte count of 13,000 cells/μL, and her electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated first-degree atrioventricular block. Her urine culture grew Escherichia coli, for which she was started on ceftriaxone.

Blood cultures drawn three days after initiation of ceftriaxone treatment were negative. She subsequently developed a cough productive of mucopurulent sputum that progressed to hemoptysis and hypoxemic respiratory failure, and required endotracheal intubation. A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest ruled out pulmonary embolism, but demonstrated focal consolidations consistent with multifocal pneumonia. A bronchoscopy revealed bleeding from the left upper lobe without any lesions. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) demonstrated mitral and aortic valve thickening with a small vegetation on the mitral valve. Infective endocarditis was suspected, and the patient’s antibiotic therapy was broadened to ceftriaxone and vancomycin.

During her hospitalization, the patient developed an acute kidney injury, with her creatinine rising to 2.1 mg/dL from 0.7 mg/dL on presentation. Further laboratory testing revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 78 mm/hr (ref: 0–20) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 12.7 mg/L (ref: 0.1–3.0), a rheumatoid factor of 41 IU/mL (ref: <14) and a positive C-ANCA with a titer >1:160.

The patient’s presentation with pulmonary hemorrhage, acute kidney injury and high C-ANCA titer led to a diagnosis of GPA. She was treated with pulse dose steroids for three days and concurrently started on plasma exchange, of which two cycles were completed. She was then placed on 240 mg/day of methylprednisolone.

Twelve days after her initial presentation, the patient was transferred to our institution to obtain a renal biopsy. On arrival, she was intubated and afebrile with a heart rate of 123 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 143/72 mmHg. Examination demonstrated a III/VI systolic murmur heard across the precordium, as well as splinter hemorrhages and purpuric periungual lesions in several bilateral fingers and toes, and peripheral edema in bilateral upper and lower extremities.

Her laboratory studies were notable for a total leukocyte count of 21,000 cells/μL and a creatinine of 2.0 mg/dL. Her complement levels were decreased, with a C3 of 31 mg/dL (ref: 81–145) and C4 <10 mg/dL (ref: 16–39), but her C1Q was 14 mg/dL (ref: 12–22), which was within normal range. Her ESR was 4 mm/hr (ref: 0–20), CRP was 14 mg/L (ref: 0.1–3.0), and fibrinogen was 83 mg/dL (ref: 144–436). Her ANCA screen was positive for C-ANCA, with a titer of 1:80 (ref: <1:20) and a PR3 antibody level of 606.9 CU (ref: <20). Her rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 18 IU/mL (ref: <15.9). Tests for ANA, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, anti-beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies were negative. A urinalysis revealed cloudy urine with a specific gravity of 1.012, 1+ protein, 3+ blood, and three to five red blood cells per high-power field. Further urine testing revealed a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 1.31.

A chest X-ray demonstrated hazy perihilar opacities and small bilateral pleural effusions, and a chest CT scan demonstrated an upper lobe predominant diffuse opacification that was consistent with pulmonary hemorrhage (see Figure 1). The patient was continued on a one-month antibiotic regimen of vancomycin and ceftriaxone and also maintained on 240 mg/day of methylprednisolone. Further immunosuppressive agents were not started due to concern for infective endocarditis.

A repeat TEE demonstrated a vegetation on the mitral valve and thickened mitral valve leaflets, with mild regurgitation at the aortic, mitral and tricuspid valves. A skin biopsy of a periungual lesion demonstrated epidermal necrosis with acute inflammation and thrombi present, but vasculitis was not identified.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain did not reveal any evidence of central nervous system vasculitis. A renal biopsy demonstrated necrotizing glomerulonephritis with crescents and without immune complex deposits, which was consistent with an ANCA-mediated glomerulonephritis (see Figure 2). A repeat bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage revealed active bleeding from the right upper lobe that was concerning for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

We determined the patient’s presentation was most consistent with GPA, and treatment was initiated with 375 mg/m2 of rituximab once per week for four weeks. In addition, plasma exchange was resumed, of which three cycles were completed (a total of five cycles).

Despite receiving extensive immunosuppressive treatments, the patient’s renal function continued to worsen, necessitating placement on regular hemodialysis. Further blood cultures and a lower respiratory culture did not grow any organism. Infectious disease tests for Bartonella henselae IgG and IgM, Coxiella burnetii IgG phases I and II, Brucella antibodies, HIV antibodies and DNA, hepatitis C virus antibodies and quantiferon-gold tuberculosis (TB) were negative.

Twenty-nine days after her initial presentation, the patient was extubated, but maintained a persistent oxygen requirement. The patient’s steroid dose was slowly tapered over her hospital course, eventually switching from methylprednisolone to prednisone, and down to a prednisone dose of 40 mg/day. During her recovery after extubation, it became evident that she was severely deconditioned and unable to leave her bed. She also had difficulty swallowing and suffered from multiple aspiration events, requiring placement of a gastrostomy tube for feeding.

Forty-nine days after her initial presentation, the patient developed respiratory distress thought to be secondary to aspiration, but declined any escalation in care, and she expired shortly thereafter. The patient’s family declined an autopsy.

Discussion

We present the case of a patient with GPA, whose clinical and laboratory findings were consistent with both an infective endocarditis and a small vessel vasculitis. The positive C-ANCA and PR3 antibody found during this patient’s workup did not provide any utility in discerning between these two diseases. The similarity in presentation between patients with ANCA-positive infective endocarditis and ANCA-associated vasculitis with endocardial involvement has been documented in the literature, and these cases are most often associated with a positive C-ANCA or PR3 antibody.7

The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is based on the modified Duke criteria.8 Although a definitive diagnosis can be provided only after histologic and microbial analysis of a vegetation or cardiac specimen, a clinical diagnosis of possible infective endocarditis can be made using the Duke criteria with the presence of one major and one minor criterion or of three minor criteria. The two major criteria are:

- A positive blood culture; and

- Evidence of endocardial involvement (an echocardiogram demonstrating a vegetation, an abscess or new valvular regurgitation).

The five minor criteria are:

- A predisposing condition;

- A fever;

- Vascular and embolic phenomena (including arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts and Janeway lesions);

- Immunological phenomena (including glomerulonephritis, Osler nodes and rheumatoid factor); and

- Microbiological evidence of infection that does not satisfy the major criterion.

A vegetation is defined as an oscillating intracardiac mass on a valve or supporting structures, in the path of regurgitant jets or on implanted material in the absence of an alternative anatomic explanation.

Our patient satisfied one major criterion: endocardial involvement with an echocardiogram demonstrating a mitral vegetation. In addition, she satisfied three minor criteria: a predisposing condition of dental infection and dental surgery preceding her presentation, embolic phenomenon of splinter hemorrhages in the digits and immunological phenomena of glomerulonephritis with reduced complement levels and an elevated rheumatoid factor. Therefore, our patient would meet the criteria to assign a clinical diagnosis of possible infective endocarditis.

On the other hand, no well-established diagnostic criteria exist for the diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis or GPA. Many physicians refer to the 1990 ACR classification scheme, which contains four criteria: nasal or oral inflammation, abnormal chest radiograph (with nodules, infiltrates or cavities), abnormal urinary sediment (with hematuria or red cell casts) and granulomatous inflammation on biopsy. The presence of two or more criteria yields a sensitivity and specificity of 88.2% and 92.0%, respectively for GPA.9 However, these criteria were developed prior to the routine use of ANCA and are not recommended for diagnostic purposes.

The diagnosis of GPA is typically made using clinical judgment by evaluating a patient’s symptoms together with laboratory and imaging findings while excluding other possible diagnoses, and by observation of improvement on immunosuppressive therapies.10

Our patient had many signs and symptoms that would suggest GPA, including a purpuric rash, hemoptysis and pulmonary hemorrhage resulting in respiratory failure and renal failure with hematuria. Her laboratory findings of an elevated ESR and CRP, and positive C-ANCA and PR3 antibodies, as well as lung opacities seen on chest X-ray and CT scan, were also all consistent with GPA. Her periungual skin biopsy contained thrombotic lesions more consistent with embolic phenomena from endocarditis rather than a vasculitis. However, the renal biopsy demonstrated a necrotizing glomerulonephritis with crescents and without immune complex deposits, which strongly favored GPA over infective endocarditis.

The presence of a mitral vegetation on echocardiogram in our patient was a key finding that made differentiation between infective endocarditis and ANCA-associated vasculitis difficult. Cardiac involvement in GPA is rarer than involvement of other organ systems, with a prevalence reported in major studies ranging from 3.3% to 13%.11-13 However, the findings of these studies are inconsistent regarding the presence of any difference in outcomes between patients with cardiac involvement compared with those without. ANCA-associated vasculitis specifically involving the cardiac valve has been observed and appears to occur in patients with mostly C-ANCA or PR3 antibody positivity, although some cases were reported prior to the use of ANCA testing. Most commonly affected is the aortic valve, followed by the mitral valve, and pathologic assessment of these affected valves yielded nonspecific inflammation and scarring.14

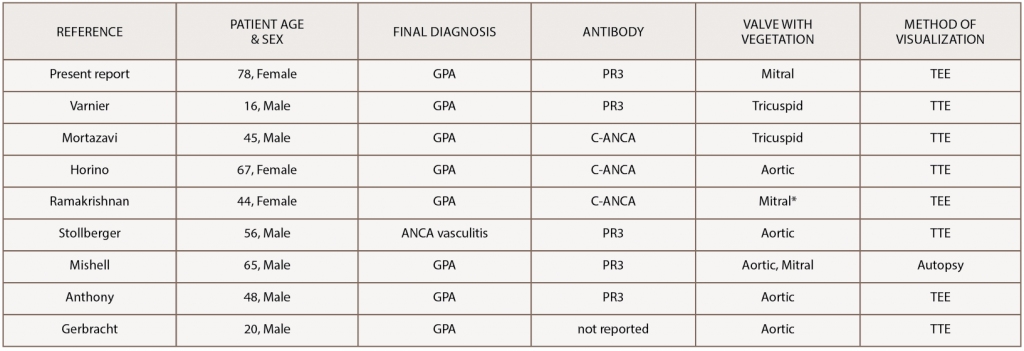

Even more rare is ANCA-associated vasculitis causing vegetations on the cardiac valves, as was the case with our patient. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature (see Table 1).15-22 Our case is unique because the majority of these cases presented with aortic valve vegetations, and our patient had a mobile vegetation on her native mitral valve, which was visualized on echocardiogram.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Reported Cases of GPA with a Vegetation on a Cardiac Valve

*patient had a prosthetic mitral valve from complications of previous rheumatic heart disease

GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; PR3, proteinase 3; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram

Ultimately, a combination of findings resulted in the diagnosis of GPA and initiation of immunosuppressive treatment in our patient. The renal biopsy demonstrating crescentic necrotizing glomerulonephritis without the immune complex deposits that would be expected in infective endocarditis and the finding of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage on bronchoalveolar lavage both supported GPA over infective endocarditis. The patient’s negative blood cultures and negative testing for Bartonella, Coxiella, Brucella, HIV and TB, as well as lack of response to the initial antibiotic treatment, all lowered the suspicion for infective endocarditis. The combination of these features and the patient’s response to treatment with high-dose steroids, rituximab and plasma exchange led to the final diagnosis of GPA.

Unfortunately, although the vasculitis appeared to be responding to treatment, the patient was unable to overcome her overall decompensation and, therefore, was unable to survive her illness.

Conclusions

GPA is a small vessel vasculitis that typically affects the respiratory tract and kidneys, with cardiac involvement being uncommon. Patients with small vessel vasculitis can present with signs and symptoms similar to those of infective endocarditis, and a positive ANCA can be seen in both conditions, which further complicates the assignment of a diagnosis. Vegetations on the cardiac valves are typically associated with infective endocarditis and constitute one of the major criteria for its diagnosis. However, valvular vegetations can also result from small vessel vasculitis.

Diagnostic difficulty can lead to a delay in initiation of the proper treatment, and a thorough evaluation of the patient is required to determine the final diagnosis and correct management in a timely manner.

Harry Subramanian is a medical student at the Yale School of Medicine. He will be pursuing a residency in diagnostic radiology at the Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Harry Subramanian is a medical student at the Yale School of Medicine. He will be pursuing a residency in diagnostic radiology at the Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Ravi B. Sutaria, MD, is a graduating fellow of Rheumatology at the Yale School of Medicine. Prior to joining Yale he was a clinical instructor of medicine at Jacobi Medical Center at North Central Bronx Hospital in New York during his time as a hospitalist. He is pursuing research establishing the efficacy of DMARDs in the treatment of chronic rheumatism as result of emerging viral infections, such as chikungunya. He is also interested in interventional/diagnostic musculoskeletal ultrasound, particularly in patients with autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

Ravi B. Sutaria, MD, is a graduating fellow of Rheumatology at the Yale School of Medicine. Prior to joining Yale he was a clinical instructor of medicine at Jacobi Medical Center at North Central Bronx Hospital in New York during his time as a hospitalist. He is pursuing research establishing the efficacy of DMARDs in the treatment of chronic rheumatism as result of emerging viral infections, such as chikungunya. He is also interested in interventional/diagnostic musculoskeletal ultrasound, particularly in patients with autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

Fotios Koumpouras, MD, is assistant professor of medicine and director of the Yale Lupus Program. He is an active member of the ACR, the Arthritis Foundation and the Lupus Foundation. In addition to SLE, Dr. Koumpouras has an interest in lupus biomarkers, pregnancy in rheumatic disease, psoriatic arthritis, diagnostic and treatment dilemmas, adolescent arthritis, lupus and the heart, gout and the gender gap of autoimmune disorders.

Fotios Koumpouras, MD, is assistant professor of medicine and director of the Yale Lupus Program. He is an active member of the ACR, the Arthritis Foundation and the Lupus Foundation. In addition to SLE, Dr. Koumpouras has an interest in lupus biomarkers, pregnancy in rheumatic disease, psoriatic arthritis, diagnostic and treatment dilemmas, adolescent arthritis, lupus and the heart, gout and the gender gap of autoimmune disorders.

Disclosures

None of the authors reports any relevant disclosures for this project, but Dr. Koumpouras reports he has previously received grant funding from NIH, NIAMS and Yale University and conducted clinical trials with Merck, Xencor, GSK, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, UCB and the Lupus Clinical Investigators Network.

References

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Lutalo PM, D’Cruz DP. Diagnosis and classification of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (aka Wegener’s granulomatosis). J Autoimmun. 2014;48–49:94–98.

- Comarmond C, Cacoub P. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener): Clinical aspects and treatment. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Nov;13(11):1121–1125.

- Grant SC, Levy RD, Venning MC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis and the heart. Br Heart J. 1994 Jan;71(1):82–86.

- Mahr A, Batteux F, Tubiana S, et al. Brief report: Prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in infective endocarditis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Jun;66(6):1672–1677.

- Weiner M, Segelmark M. The clinical presentation and therapy of diseases related to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA). Autoimmun Rev. 2016 Oct;15(10):978–982.

- Chirinos JA, Corrales-Medina VF, Garcia S, et al. Endocarditis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Apr;26(4):590–595.

- Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;30(4):633–638.

- Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1101–1107.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1997 Nov 20;337(21):1512–1523.

- Guillevin L, Pagnoux C, Seror R, et al. The Five-Factor Score revisited: Assessment of prognoses of systemic necrotizing vasculitides based on the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG) cohort. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011 Jan;90(1):19–27.

- McGeoch L, Carette S, Cuthbertson D, et al. Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Rheumatol. 2015 Jul;42(7):1209–1212.

- Walsh M, Flossmann O, Berden A, et al. Risk factors for relapse of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Feb;64(2):542–548.

- Lacoste C, Mansencal N, Ben M’rad M, et al. Valvular involvement in ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis: A case report and literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 Feb 23;12:50.

- Anthony DD, Askari AD, Wolpaw T, McComsey G. Wegener granulomatosis simulating bacterial endocarditis. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Aug 9–23;159(15):1807–1810.

- Gerbracht DD, Savage RW, Scharff N. Reversible valvulitis in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Chest. 1987 Jul;92(1):182–183.

- Horino T, Takao T, Taniguchi Y, Terada Y. Non-infectious endocarditis in a patient with cANCA-associated small vessel vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 May;48(5):592–594.

- Mishell JM. Cases from the Osler Medical Service at Johns Hopkins University: Cardiac valvular lesions in Wegener’s granulamatosis. Am J Med. 2002 Nov;113(7):607–609.

- Mortazavi M, Nasri H. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) presenting as the right ventricular masses: A case report and review of the literature. J Nephropathol. 2012 Apr;1(1):49–56.

- Ramakrishnan S, Narang R, Khilnani GC, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis mimicking prosthetic valve endocarditis. Cardiology. 2004;102(1):35–36.

- Stollberger C, Finsterer J, Zlabinger GJ, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-negative antiproteinase 3 syndrome presenting as vasculitis, endocarditis, polyneuropathy and Dupuytren’s contracture. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003 Jul;12(4):530–534.

- Varnier GC, Sebire N, Christov G, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis mimicking infective endocarditis in an adolescent male. Clin Rheumatol. 2016 Sep;35(9):2369–2372.