Based on experience from the conduct of DMOAD trials in the last decades, such studies present major challenges (see Table 2). A number of lessons have been learned and are worth sharing.23,26 First, protocols for these trials were highly variable from one study to another. For example, inclusion/exclusion criteria regarding disease severity, demographic, risk factors, and structural changes differed quite significantly among the studies and could have an obvious impact on the results, complicating the analyses and comparisons of the results of a particular drug with others. Efforts should be made to better standardize these criteria to ensure a homogeneous and representative population. This would also allow better standardization and balancing of the risks factors associated with the disease progression, which is essential in such studies.

The whole issue about the extent of effect that a DMOAD should have on disease symptoms to be acceptable is also problematic. To start with, the questionnaires and evaluation scales recommended and used in these studies have been imported from short-term trials dealing with the efficacy of OA treatment on symptoms. Are they reliable for long-term DMOAD studies? Maybe. Maybe not. This question is of the utmost importance and needs to be answered.

One of the real challenges in the development of DMOADs is finding an ideal study outcome measure. Ideally, a hard target such as the reduction in the need for total joint replacement is most interesting (see Table 1). However, as a practical matter, since the incidence of total joint replacement during clinical trials is fairly low, particularly in knee OA trials, the concept of a responder criteria combining the impact of DMOAD treatment of disease symptoms and progression of structural changes, has recently been advocated, and should be considered more carefully.27

The major goal of a DMOAD treatment should be to reduce the progression of joint structural changes, namely cartilage loss. There is a general consensus that a study duration of two years is realistic. The study joint should generally be a weight-bearing one (e.g., knee or hip), unless a specific indication for another joint (e.g., hand) is made. An important issue is whether studying one target joint only is adequate and representative of a drug’s effect. If the effect of treatment is systemic, should more than one joint be studied? This question is of high relevance and needs to be addressed.

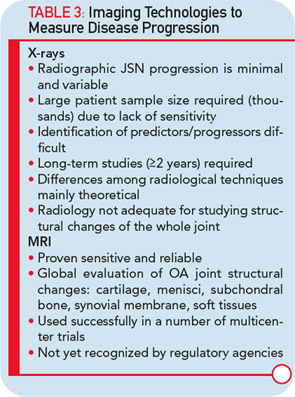

The imaging method used for the assessment of the DMOAD effect has traditionally been X-rays, which are still recommended today. Should this technology still be the gold standard, given the progress made in the field of OA imaging in the last decade? Probably not. This conclusion appears especially true when one realizes the limitations imposed by the use of X-rays (see Table 3).22,23 Advanced technology, such as MRI, can provide more comprehensive and reliable information on the progression of the disease and the effects of DMOAD treatment (see Table 3 and Table 4).20,28,29 MRI is an approved imaging modality and has been used as reference in many fields of research, including trials in cancer and central nervous system disease for a long time. The time has come for the field of OA research to follow suit because this technology can assist in the development of proof-of-concept DMOAD studies and reduce the number of patients to be included in phase II and III trials. Such a change will make DMOAD development programs more affordable and, at the same time, bring new hope to OA patients.