The impressive progress of medical knowledge and technology reinforces our trust in the scientific methodology that made it all possible. However, that progress also creates risks related to the primary goal of medical care: to serve our patients’ interests and enjoyment of life in the best possible way.

The impressive progress of medical knowledge and technology reinforces our trust in the scientific methodology that made it all possible. However, that progress also creates risks related to the primary goal of medical care: to serve our patients’ interests and enjoyment of life in the best possible way.

In this article we present our views on how the currently prevailing treatment strategy can be taken a step forward to simultaneously sharpen our therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and foster empathy and patient-centered care. The proposal may be applicable to a variety of conditions, in addition to RA.

Linda’s Clinical Scenario

“Linda” is a 37-year-old math teacher and mother of two—a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old. She was diagnosed with RA 18 months ago, 10 weeks after her first symptoms appeared. Pain and morning stiffness made it impossible for her to carry out her family duties and kept her out of work for three months. With medication, her symptoms have significantly improved.

Linda is being treated by “Dr. Snow,” who runs a busy, but well-organized and evidence-based, clinic. Every three months, Linda has an appointment and fills in several questionnaires about her disease. She feels lucky to have found Dr. Snow, and he has been pleased with her progress so far.

Linda’s disease activity has been assessed systematically by support nurses, and a remission target has been consistently pursued, although this was not exactly the subject of shared decision making. Her therapy was stepped up, as recommended, and the results have been positive—until now. Linda’s Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) score has increased beyond the low disease-activity level.

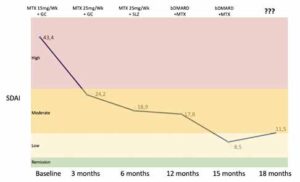

Dr. Snow must now decide whether to switch the biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (bDMARD) Linda has been taking to another agent. Figure 1 shows Dr. Snow’s register of Linda’s disease activity levels, as well as the DMARD scheme followed until today.

Figure 1: Linda’s Disease Activity Evolution & Treatment Scheme

(Legend: bDMARD, biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index; SLZ, sulfasalazine)

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Treat to Target

The guiding principles of treat to target, described for RA more than a decade ago, are:1

- Selecting a target (i.e., remission or, at least, low disease activity in every patient) and a method for measuring it;

- Assessing the target at pre-specified time points (e.g., every three months);

- Making a commitment to change the therapy if the target is not achieved; and

- Exercising shared decision making.

These have been incorporated as guiding principles in the EULAR and ACR treatment recommendations for RA since 2010 and 2012, respectively.2,3 These treat-to-target principles represented a major advance in our field, providing the best possible certainty of reducing or halting the progression of joint damage and disability.4

Following this success, treat to target has also been proposed for other rheumatic diseases, such as axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis (especially psoriatic arthritis), gout and systemic lupus erythematosus.5 Other medical specialties, including neurology and gastroenterology, are also starting to consider treat to target.6,7

One issue of contention in treat to target is how strict one must be in pursuing the treatment target. EULAR recommendations state that if “the target has not been reached by six months, therapy should be adjusted.”

The only nuance to this recommendation is: “One should consider the desired treatment target as well as various patient factors, including comorbidities, when making treatment adaptations.”

No specific exceptions to the rule of adapting medication in the case of failing to reach the target are offered.2

In a recent paper celebrating the anniversary of 10 years of the treat-to-target strategy, Josef Smolen, MD, PhD, its most prominent advocate, stated,5 “Treat to target is not an idée fixe, a strategy that has to be adhered to under all circumstances, but rather should be applied with prudency and several caveats in mind. … In clinical practice … being close to that threshold (even if slightly above the LDA/MDA threshold) should be seen as a success of the therapeutic intervention and not necessarily elicit a change of the treatment regimen.”

These nuances make no specific reference to the different parameters being used to assess disease activity and define the target. However, among the objections raised to treat to target are uncertainties regarding whether standard disease activity scores truly reflect disease activity or could be unduly influenced by patient-specific factors or comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia; the most appropriate definition of remission; and other patient-related limitations, such as drug intolerance and toxicity, which can limit therapeutic choices.8

In fact, the concerns regarding patient-specific factors, including comorbidities, have been repeatedly voiced as a reason for concern, especially regarding patients’ input into the metrics of disease activity and the definition of the target through the patient global assessment (PGA) of disease activity.

Back to the Scenario

Following treatment recommendations, Dr. Snow is inclined to change the bDMARD, despite the nuances described above. After all, Linda has always been a positive and reliable patient, and the SDAI is now above target. Another targeted agent or reinforced immunosuppressive therapy will certainly improve her condition.

Remission Definitions & Impact of PGA

The provisional definitions of remission jointly proposed by the ACR and EULAR in 2010 recommend the use of either a Boolean definition or an SDAI score of 3.3 or less in clinical trials.9 The use of a Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 2.8 or less is also used for clinical practice in the absence of CRP levels.

These definitions were primarily designed for clinical trials, but their use in clinical practice was predicted and rapidly became very popular, especially in Europe. All of these definitions include the PGA, and this is the only patient-reported outcome measure included in the definition of target.

The PGA is a practical, easy-to-administer measure, with good validity on its face and test-retest reliability. Its incorporation in these criteria was justified mainly by its relationship with disease activity and ability to distinguish active treatments from placebo.10 Its inclusion was also informed by the need to have a representation of the patient’s view in an era of patient-centered care philosophy.11

The use of the PGA in the definition of target has raised numerous concerns, which can be coalesced in three main domains: 1) The PGA has a poor relationship with disease activity, blurring the target for immunosuppressive therapy; 2) including the PGA increases the risk of overtreatment; and 3) the PGA provides a poor representation of the patient’s needs, but creates the illusion the patient is properly cared for.

PGA & Disease Activity

We, and others, have robustly demonstrated the PGA is more strongly associated with pain, function, fatigue, physical well-being and psychological domains, such as depression, anxiety and personality traits, as well as comorbidities (e.g., fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis) or years of formal education, than with markers of inflammation. This is especially true in the lower levels of disease activity, in which the definition of the target is more decisive.12-14

The discrepancy between the PGA and disease activity tends to increase with disease duration and age, when cumulative damage and comorbid causes of pain and function loss become more prominent.

We have also demonstrated that there is no difference between subclinical inflammation, as evaluated by extensive ultrasound examination and the ACR/EULAR, Boolean-based remission (i.e., 4V remission) and PGA near-remission (i.e., the PGA is the only Boolean criteria >1) descriptions.15

The PGA is essentially a measure of disease impact and not of disease activity.

That is one of the bases for our position that the PGA blurs the target and our proposal to remove it from the current definition of remission.12

In addition, a three-variable definition of remission (without the PGA) better predicts radiographic damage over two years than the full 4V-remission definition. This was demonstrated through individual patient data meta-analysis from 11 randomized controlled trials that included 5,792 patients.16

Risk of Overtreatment

Our group, among many others, has provided evidence that of the four variables included in the Boolean definition of remission (i.e., swollen and tender joints, CRP and PGA) the PGA is the most important single reason patients don’t reach remission. It is responsible for 60–80% of patients who don’t reach remission, depending on the studies considered.

This condition, PGA near remission, was over 50% more common than 4V remission in a meta-analysis of 12 clinical cohorts, with more than 23,000 patients: 19% vs. 12%.17 Overall, 61% of patients with RA otherwise in remission miss the established target solely due to a PGA score greater than 1.

These patients are highly unlikely to be improved by additional immunosuppressive therapy because the disease process is already under (nearly) full control. They are, therefore, exposed to the risk of overtreatment if the treat-to-target strategy and EULAR recommendations are followed strictly.

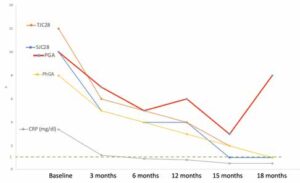

It has been argued that wise clinicians will not increase immunosuppression in patients whose only obstacle to remission is the PGA, such as Linda in our scenario (see Figure 2). Shouldn’t clinical wisdom also be incorporated in recommendations, especially when computer-based treatment decisions are being considered?18

Poor Representation of Patient Needs

The PGA provides no information whatsoever on the underlying causes of persistent disease impact on a patient’s quality of life. This makes it useless to help the caring physician decide what sort of adjunctive measures, if any, may be appropriate to improve the patient’s condition, especially after remission of the biologic process has been achieved. In fact, a high PGA can be caused by a variety of different domains, including pain, function and depression, requiring different interventions.13

Figure 2: Linda’s Individual Components of Disease Activity

(Legend: CRP, C-reactive protein; TJC28, Tender Joint Counts in 28 joints; SJC28,

Swollen Joint Counts in 28 joints; PGA, patient’s global assessment of disease activity; PhGA, physician’s global assessment of disease activity)

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Moreover, it is reasonable to believe that incorporating this single patient-reported outcome in the definition of treatment target feeds the illusion that disease impact is accounted for and, in our opinion, wrongly relieves the clinician of the obligation to pay additional attention to the patient’s perspective.

Back to the Scenario

Having these considerations in mind, Dr. Snow decides to take a look at the individual domains of disease activity (see Figure 2).

The PGA is the only criterion that worsened from the previous visit. In fact, it is the only criterion above 1—the sole factor keeping Linda from reaching Boolean remission criteria.

Dr. Snow decides not to adjust Linda’s current therapy and sets out to understand the reasons underlying the persistent impact of the disease, despite biologic remission. He finally decides to treat her depression.

The Dual-Target Strategy

The dual-target strategy involves two main changes to the current standards:

- Sharpening the current definitions of remission, the biologic target, by removing PGA and using these definitions to guide immunosuppressive therapy, and

- Adding a novel target focused on the impact of disease upon the life of the patient (symptom remission).12,19,20

The operational definition of the second target is still to be defined, but it would be best served by instruments that reflect the multidimensional nature of disease impact, as perceived by patients. We believe the RA Impact of Disease (RAID) score is especially suited for this purpose.21 RAID addresses seven domains of disease impact selected by patients with RA: pain, functional capacity, fatigue, physical and emotional wellbeing, sleep, and coping.

Simpler instruments, such as the Patient Experienced Symptom State (PESS), may be used to screen for patients in need of more detailed impact evaluation.22

With the dual-target proposal, we seek to ensure the patient’s perspective is reinforced as the central target of disease management. Controlling the disease process, the current target, is an important means to that end, but not a sufficient warranty, as seen above.

Empathy

The health professional’s goal is to serve the patient’s interests in the best possible way.

The patient knows things the clinician often ignores: the symptoms, their intensity and their relative impact on their quality of life. Similarly, the clinician knows things the patient may ignore or be unaware of: that controlling the disease process is pivotal to helping the patient achieve their quality-of-life goals and to prevent irreversible structural and functional damage.

This lack of mutual awareness may lead to unintended consequences, such as the use of stronger medications than the patient feels is warranted or the withdrawal of agents that seem to be working. Because neither the clinician nor the patient wants this to be the end result of the encounter, we must seek solutions that limit the likelihood they will occur.

We believe the treatment target should incorporate the improvement of the patient’s experience beyond mere disease control. That imposes the requirement on the clinician to understand the needs and desires of the patient through active listening in a context that rheumatologists master exceedingly well: true doctor-patient relationships.

Active listening requires not just time, but presence. Presence is when we engage our patients without interrupting, judging or minimizing. It is more than clock time, and although it may appear ineffable, patients know when the doctor is present during their visit. As Ronald Epstein points out in his book, Attending, doctors often don’t do this well.23

A study from the Mayo Clinic supports this: The researchers qualitatively analyzed patients who were discordant in their global response with their providers’ findings. Such patients generally felt they weren’t being listened to and experienced a gap in empathy.24

Nothing will assist us more in our effort to achieve disease control and address the patient’s goals than placing the patient’s views and experiences at the center of the target. The dual-target strategy may play an important role in framing and promoting this path.

Ricardo J.O. Ferreira, RN, PhD, is a specialist nurse and researcher at the Rheumatology Department of Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, and researcher at Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing (UICiSA:E), Nursing School of Coimbra (ESEnfC), Coimbra, Portugal. He currently serves as chair of the EULAR Health Professionals in Rheumatology (HPR) Committee.

Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, is professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, holds the R.J. Fasenmyer Chair of Clinical Immunology and the Theodore F. Classen, DO, Chair of Osteopathic Research and Education, and serves as the vice chair of the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases at the Cleveland Clinic.

José A.P. da Silva, MD, PhD, is professor of rheumatology at the Faculty of Medicine University of Coimbra, and head of rheumatology at Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. He previously served as president of the European Board of Rheumatology and chair of the EULAR Education Committee.

References

- Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jan;75(1):3–15.

- Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jun;79(6):685–699.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Jan;68(1):1–25.

- Stoffer MA, Schoels MM, Smolen JS, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Results of a systematic literature search update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jan;75(1):16–22.

- Smolen JS. Treat to target in rheumatology: A historical account on occasion of the 10th anniversary. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;45(4):477–485.

- Agrawal M, Colombel JF. Treat-to-target in inflammatory bowel diseases, what is the target and how do we treat? Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019 Jul;29(3):421–436.

- Jacobs BM, Giovannoni G, Schmierer K. No evident disease activity—more than a risky ambition? JAMA Neurol. 2018 Jul 1;75(7):781–782.

- van Vollenhoven R. Treat-to-target in rheumatoid arthritis—are we there yet? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019 Mar;15(3):180–186.

- Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Mar;63(3):573–586.

- Gotzsche PC. Sensitivity of effect variables in rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of 130 placebo controlled NSAID trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1313–1318.

- Gnanasakthy A, Barrett A, Norcross L, et al. Use of patient and investigator global impression scales: A review of Food and Drug Administration-approved labeling, 2009 to 2019. Value Health. 2021 Jul;24(7):1016–1023.

- Ferreira RJO, Duarte C, Ndosi M, et al. Suppressing inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: Does patient global assessment blur the target? A practice-based call for a paradigm change. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Mar;70(3):369–378.

- Ferreira RJO, Dougados M, Kirwan JR, et al. Drivers of patient global assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who are close to remission: An analysis of 1588 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Sep 1;56(9):1573–1578.

- Ferreira RJO, Carvalho PD, Ndosi M, et al. Impact of patient’s global assessment on achieving remission in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A multinational study using the METEOR database. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Oct;71(10):1317–1325.

- Brites L, Rovisco J, Costa F, et al. High patient global assessment scores in patients with rheumatoid arthritis otherwise in remission do not reflect subclinical inflammation. Joint Bone Spine. 2021 Jun 21;88(6):105242.

- Ferreira RJO, Welsing PMJ, Jacobs JWG, et al. Revisiting the use of remission criteria for rheumatoid arthritis by excluding patient global assessment: An individual meta-analysis of 5792 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Oct 6;annrheumdis-2020-217171.

- Ferreira RJO, Santos E, Gossec L, da Silva JAP. The patient global assessment in RA precludes the majority of patients otherwise in remission to reach this status in clinical practice. Should we continue to ignore this? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020 Aug;50(4):583–585.

- Jacobs JW. The Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis programme tool used in the CAMERA-I and CAMERA-II studies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 Sep–Oct;34(5 Suppl 101):S69–S72.

- Ferreira RJO, Ndosi M, de Wit M, et al. Dual target strategy: A proposal to mitigate the risk of overtreatment and enhance patient satisfaction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Oct;78(10):e109.

- Ferreira RJO, Santos EJF, de Wit M, et al. Shared decision-making in people with chronic disease: Integrating the biological, social and lived experiences is a key responsibility of nurses. Musculoskeletal Care. 2020 Mar;18(1):84–91.

- Gossec L, Paternotte S, Aanerud GJ, et al. Finalisation and validation of the rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease score, a patient-derived composite measure of impact of rheumatoid arthritis: A EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jun;70(6):935–942.

- Duarte C, Santos E, da Silva JAP, et al. The Patient Experienced Symptom State (PESS): A patient-reported global outcome measure that may better reflect disease remission status. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Nov 1;59(11):3458–3467.

- Epstein RM. Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity. New York: Scribner; 2017.

- Kvrgic Z, Asiedu GB, Crowson CS, et al. ‘Like no one is listening to me’: A qualitative study of patient-provider discordance between global assessments of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(10):1439–1447.

Editor’s note: This article represents the opinions of the authors and not necessarily those of the ACR or the editors.