Rheumatology is a discipline that has more than its share of syndromes that are mysterious in both origin and presentation. Inflammation of uncertain origin is one of the conditions that particularly intrigues us. Indeed, we are excited and challenged when patients seek our help when they present with a baffling combination of symptoms such as joint pains, skin rashes of varying description, and fever accompanied by an acute phase response. Some of these conditions have found a name—Behçet’s, Still’s disease, and Schnitzler’s syndrome, for instance—but progress towards identifying their causes, and, of greater importance, finding an effective treatment, has been slow. With progress in immunology, however, some of the mystery is dissipating, and new treatments are on the horizon.

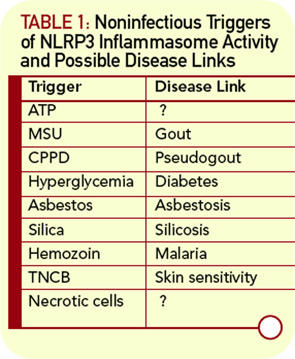

The pioneering studies of Daniel Kastner, MD, PhD, at the National Institutes of Health and others have gained recognition for a group of diseases that are now called the autoinflammatory syndromes; some of theses disease are hereditary and are now much better understood in terms of molecular pathology.1 A common feature of this group of diseases is systemic inflammation in the absence of known infectious agents, often presenting a chronic course that responds only partially to treatment. Some authors also call this process sterile inflammation to distinguish it from sepsis.

A major breakthrough in our understanding of these inflammatory syndromes came with the characterization of the inflammasome. Despite initial skepticism about the nature and role of this subcellular structure, the inflammasome is now widely accepted as a key regulator of inflammatory processes. Importantly, the functional activity of the inflammasome provides an explanation for hitherto difficult to explain syndromes. It is increasingly clear that the inflammasome may be involved in multiple inflammatory processes. The inflammasome also brings back into the limelight the role in disease of interleukin (IL)-1b, a cytokine that has up to now been overshadowed by tumor necrosis factor–α, at least in rheumatology.

Some History

The term “inflammasome” was coined by Jürg Tschopp and colleagues at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland to describe a caspase-activating complex that processes pro–IL-1b (35kd) to mature IL-1b (17kd form). Two research groups, including Tschopp’s, published around the same time that an intracellular complex composed of caspase-1, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein with a caspase-recruitment domain (ASC), and nucleotide binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing protein (NLRP) is required for IL-1b processing in macrophages.2,3 This initial observation has led to an explosion of studies that have extended our concepts of the inflammasome. As now recognized, the inflammasome can be composed of different pro-inflammatory caspases as well as different NLRP-family proteins, and its substrates include IL-18 and possibly IL-33, cytokines that belong to the IL-1 family.4