Updates from the ACR Convergence 2023 Review Course, part 1

Updates from the ACR Convergence 2023 Review Course, part 1

SAN DIEGO—The pre-conference Review Course at ACR Convergence 2023, moderated by Noelle Rolle, MBBS, assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology, associate program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, and Julia Schwartzmann-Morris, MD, associate professor, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, N.Y., tackled numerous important topics in rheumatology. Here, we report on the first presentation of Saturday, Nov. 11.

Laura Kopplin, MD, PhD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, discussed inflammatory disease of the eye. Dr. Kopplin began her talk by describing key concepts in uveitis.

Uveitis

Many rheumatologists see patients referred for uveitis, and Dr. Kopplin noted that it is essential the specific type of uveitis (i.e., anterior, intermediate, posterior or panuveitis) be identified because the differential diagnosis for each condition is different.

Dr. Laura Kopplin

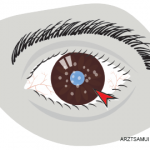

Anterior uveitis is the classic form—the one many clinicians think about when they hear uveitis. Anterior uveitis is defined by the presence of cells or cellular aggregates visible in the anterior chamber of the eye on exam. This tends to be painful for most patients, although it may be asymptomatic in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Common causes of anterior uveitis include spondyloarthropathies, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease and a number of infections, such as syphilis and tuberculosis. Dr. Kopplin provided several clinical pearls, including:

- Inflammatory bowel disease-associated anterior uveitis tends to be bilateral; and

- Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome may be an under-recognized cause of anterior uveitis.

TINU is more common in younger patients, may present with bilateral anterior uveitis and diagnosis may, in part, rely on testing urine beta-2 microglobulin, which is elevated in the condition.

Regarding prognosis, the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group is an international group of experts that has created a grading system for anterior uveitis, which can help predict the risk of vision loss in patients.

Intermediate uveitis is a form of the condition that mostly manifests with vitritis. To diagnose the condition properly, a dilated eye exam is needed. There is an association between multiple sclerosis (MS) and intermediate uveitis, but Dr. Kopplin does not recommend obtaining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain and spinal cord routinely in all patients with intermediate uveitis. Rather, such testing should be based on risk factors for, or signs of possible, MS. Intermediate uveitis can be graded using the degree of vitreous haze, which is based on the clarity of view of the posterior segment on funduscopic exam.

Posterior uveitis is among the rarer forms of uveitis, but it is also the form of uveitis that can be most associated with loss of vision. The challenge with this condition is that visual symptoms may occur even in the absence of significant pain. Among the infections that can cause posterior uveitis are syphilis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, endogenous endophthalmitis and viral causes, such as herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster virus and cytomegalovirus. Vision loss in posterior uveitis can occur quickly, and it may be necessary to rapidly escalate therapy to include one or more medications, such as methotrexate and/or mycophenolate mofetil.

Panuveitis is a generalized inflammation that includes the whole of the uveal tract, as well as the retina and vitreous humor. Dr. Kopplin said this particular form of uveitis can be seen in patients with sarcoidosis. Like the other forms of uveitis, infectious causes must be excluded, in particular with testing for syphilis and tuberculosis. Lyme testing may be indicated for patients with various forms of uveitis, although this depends on the geographic location of the patient (i.e., if it is a Lyme-endemic area). In Dr. Kopplin’s opinion, there is a limited role for testing for toxoplasma and toxocara in most patients with uveitis.

Several uveitis syndromes are restricted to the eye. These include sympathetic ophthalmia, birdshot retinopathy, serpiginous chorioretinopathy and pars planitis. Because many of these conditions may require use of systemic immunosuppressive treatments, it is important that rheumatologists be aware of them. Rheumatologists may be called upon to manage medications for these patients while collaborating with ophthalmologists.

Other Inflammatory Eye Diseases

Moving on to other forms of inflammatory eye disease, Dr. Kopplin explained that scleritis can be diagnosed with an exam using natural light alone. Patients with scleritis will often describe a “toothache-like” pain in the eye. There is often scleral injection with a purplish hue on exam, and scleritis is very frequently due to an underlying systemic inflammatory condition. Rheumatoid arthritis is a common culprit, but entities like hepatitis, IgG4-related disease and bisphosphonate-induced scleritis are possible as well.

Episcleritis is often self-limited and is not generally associated with a great deal of pain.

Dr. Kopplin also mentioned orbital inflammatory conditions, which may include dacryoadenitis, ocular myositis and inflammation of the orbital fatty tissue.

Across uveitis, scleritis and episcleritis, an underlying cause may not be found in a substantial number of patients, and the condition is then regarded as idiopathic.

Treatment

Treatment for inflammatory diseases of the eye almost always starts with topical corticosteroid therapy. If patients fail to respond adequately, they may then be treated with systemic corticosteroids or shorter acting injectable steroids.

The next step in patients with an inadequate response would be conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), certain biologics and finally alkylating agents when needed. Some of the medications included in these treatment categories are azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine and cyclophosphamide.

Even with these treatments, only about 40–50% of patients will gain control of their disease. If DMARD therapy fails to help patients, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) inhibitor therapy is often the next step, with adalimumab and infliximab having the most robust evidence of efficacy; etanercept is less effective. Tocilizumab has been used to treat uveitis, and it appears to work well for patients with persistent uveitic macular edema. Rituximab may be an option for patients with scleritis or orbital inflammatory conditions.

Jason Liebowitz, MD, is an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York.