The findings of this study were confirmed by a smaller cohort from France that included 16 patients with persistent localized disease.10 Persistent localized disease was found to occur at a similar frequency (3.2%). Furthermore, highly potent immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide was required at a similar rate as in the larger study to control localized destructive disease of the ear-nose-throat (ENT) region or mass formation in the lungs.

In summary, a small percentage of WG remains persistently localized to the ENT region (and to adjacent structures), presents with granulomatous-type manifestations within the respiratory tract, which may lead to destruction of bone and cartilaginous structures of the nose (e.g., saddle nose, loss of concha, septum perforation) to invasion of the orbita (orbital pseudotumors), or cranial base (intracerebral lesion) with organ-threatening complications that require more aggressive immunosuppression than previously expected.

Genetic Background of AAV

Interestingly, the incidence of WG is much lower in Japan compared with European countries.14 It may be speculated that differences in genetic background are responsible for the differences in incidences of the AAV. So far, especially from European cohorts, there is evidence that AAV patients share common genetic risk factors but also have their own unique genetic variations, which confer the differences in phenotype. Whereas the PTPN22*620W allele is associated with both WG and MPA, the HLA-DPB1*0401 allele has only been identified as a risk factor for WG, but not for MPA.15–18 Interestingly, HLA-DPB1*0401 is also associated with another granulomatous disease, chronic beryllium disease. It may therefore be speculated that HLA-DPB1*0401 may confer a risk for the development of granulomatous disease, whereas PTPN22*620 W is typically associated with a positive ANCA status and may therefore convey the risk for a vasculitic phenotype. Currently, a European genome-wide association study of WG and MPA is underway to identify common and unique genetic variations in WG and MPA. In the future, a genetic characterization of Japanese populations will be required to understand the different incidence rates of AAV in Europe and Japan.

Granulomatosis of Wegener’s: Histological Features, Immunopathogenic Mechanisms

Whereas immunopathogenic mechanisms of vasculitis are thought to be well established, the driving force and pathophysiological meaning of granulomatous inflammation in WG are unknown.3 We would like to summarize information about histological features and pathomechanisms within granulomatous lesions, in short, granulomatosis.

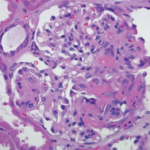

The classical histomorphologic triad of WG comprises granuloma (see the right panel of Figure 2, p. 41), geographic necrosis (see the middle panel of Figure 2, p. 41), and vasculitis.19–21 Granuloma is defined as a focus of histiocytic cells, chiefly epitheloid cells, with or without multinucleated giant cells and T lymphocytes. In WG, however, the granuloma itself is situated within a dense heterogeneous inflammatory infiltrate of bystander cells (see the right panel of Figure 2, p. 41). In fact, the typically ill-defined WG granuloma is accompanied by numerous neutrophils (PMN), diffusely dispersed macrophages/histiocytes, fibroblasts, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. T and B lymphocytes may be diffusely distributed or organized as follicle-like structures.3,19–21