BALTIMORE—Although first described by the English physician Sir Jonathan Hutchinson in the 1870s, sarcoidosis remains a prevalent—and insidious—disease in the modern world.

BALTIMORE—Although first described by the English physician Sir Jonathan Hutchinson in the 1870s, sarcoidosis remains a prevalent—and insidious—disease in the modern world.

At the 20th Annual Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases Symposium at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Michelle Sharp, MD, MHS, assistant professor of medicine and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Sarcoidosis Program, provided a thorough lecture titled, Updates in Sarcoidosis.

Considerations for Diagnosis

First, Dr. Sharp noted three elements pertinent to correctly diagnosing sarcoidosis:

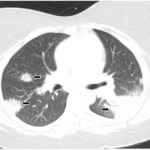

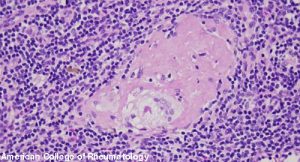

- The identification of non-caseating granulomatous inflammation on biopsy of an affected tissue;

- A clinical presentation compatible with the disease; and

- The exclusion of alternative etiologies for the patient’s signs/symptoms of disease.

Dr. Sharp stressed to the audience that the mere presence of non-caseating granulomas on a biopsy does not—in and of itself—make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Many entities may result in this histopathological finding, including lymphoma, aspergillosis, tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, histoplasmosis and vasculitis—to name just a few. Thus, it’s prudent to always think about and rule out infections and forms of malignancy while entertaining the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

The typical onset of disease occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years old, with a second peak occurring after age 60. (Note: This later onset is more common in women than men.) Although globally the incidence and prevalence of sarcoidosis is highest in Scandinavian and other Northern European countries, a three- to fourfold higher risk of disease exists for individuals who are Black vs. those who are white in the U.S.1 Being aware of these statistics is important, but Dr. Sharp advises physicians to avoid excluding the possibility of sarcoidosis in certain patients purely based on age, gender or race because any individual can be afflicted.

The immunologic hallmarks of sarcoidosis include: oligoclonal expansion of αβ+CD4+T cells, polarized Th1 immunity, regulatory T cell dysfunction and Th17/Th17.1 immunity. It has been hypothesized that microbes, including mycobacterium, may trigger this immunologic cascade; although it’s also thought that certain organic and inorganic agents may be implicated in pathogenesis of disease. This latter point has been emphasized by the observation of several studies that excess incident sarcoidosis occurred among the rescue and recovery workers exposed to debris following the World Trade Center attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.2,3

Dr. Sharp noted that sarcoidosis does not so much flare, but rather produces an undulating course of inflammation that may become clinically apparent when symptoms rise above the threshold noticeable to patients and physicians. If a patient with sarcoidosis is to go into remission, the vast majority do so within the first two or three years of their disease.