Insights from 2 Patients with Susac Syndrome

Insights from 2 Patients with Susac Syndrome

EULAR 2024 (VIENNA)—Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and spondyloarthritis are the bread and butter of most rheumatology practices. But every now and then, a consult doesn’t quite fit the mold—that one patient who presents with hearing loss, vision changes and/or neurologic dysfunction. When we receive consults like these, we’ve got to be at the top of our game because the stakes are high. Catching a brain, ear, eye syndrome early can change a life.

Dr. Ofir Dovrat

During a session at EULAR 2024, Tali Ofir Dovrat, MD, and Victoria Furer, MD, both rheumatologists from the Department of Rheumatology, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel, described two cases of Susac syndrome. They shared their center’s experiences with these patients and provided updates on the literature.

Case 1

The first patient was a 33-year-old woman. One year prior to admission, she experienced sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss. At that time, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain was normal. She presented to the neurology service with vertigo, nausea, vomiting and recurrent sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss. Shortly thereafter, she developed encephalopathy. She was confused, disoriented, couldn’t remember the names of her children and had a wide-based gait. She was afebrile, with no other systemic signs or symptoms of infection.

The patient’s laboratory tests were grossly unremarkable, with normal complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, inflammatory markers, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs). However, her cerebrospinal fluid was abnormal, with elevated white blood cells (14 mononuclear cells/mL3) and elevated protein (125 mg/dL). Her cerebrospinal fluid glucose and opening pressure were normal. Extensive infectious tests and toxicology screens were unrevealing.

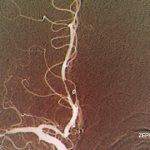

An electroencephalogram showed bilateral frontotemporal slowness—a nonspecific finding. However, the MRI of her brain showed multiple snowball lesions in the corpus callosum, cerebellum and periventricular white matter. Ophthalmologic examination showed cotton wool spots and fluorescein angiography showed bilateral branch retinal artery occlusions despite a lack of visual symptoms.

Case 2

The second patient was a 20-year-old man with a past medical history of depression. He was admitted to the emergency department with acute hearing loss, vertigo and headache. This condition was followed shortly thereafter by aphasia, confusion, paresthesia and a wide-based gait. He could not recognize his family members and had impaired memory, attention and executive function of neurologic exam. As with the first patient, his laboratory studies and infectious evaluation were normal. His cerebrospinal fluid studies were abnormal, with elevated opening pressure and protein levels (113 mg/dL).

An MRI of his brain revealed multiple snowball lesions within the corpus callosum, periventricular and subcortical white matter, as well as leptomeningeal enhancement. Audiometry showed bilateral sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss and bilateral branch retinal artery occlusions.

Diagnosis

Both of these patients presented with acute onset encephalopathy, sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss and bilateral branch retinal artery occlusions with MRIs revealing multiple lesions on the brain, including on the corpus callosum. This constellation of symptoms is consistent with Susac syndrome.

Clinical Courses

Patient 1 was treated with pulse-dose intravenous (IV) glucocorticoids followed by 60 mg of prednisone daily. She received induction IV cyclophosphamide and aspirin, demonstrating substantial improvement. After four months, she had no sign of active disease. She had some residual visual and hearing impairment but regained complete functionality. A repeat brain MRI showed chronic, inactive lesions. A slow glucocorticoid taper was started, and she was transitioned from cyclophosphamide to a maintenance dose of mycophenolate mofetil and aspirin for the next three years. At this time, immunosuppressive therapy was stopped, and she has remained in clinical remission.

Patient 2 was also treated with pulse-dose IV glucocorticoids, induction IV cyclophosphamide and aspirin, with improvement. However, he suffered a flare one month later, with new branch retinal artery occlusions and lesions found on a brain MRI. He was treated with repeat pulse-dose glucocorticoids, induction IV cyclophosphamide and the addition of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Two months later, his disease flared again, and he required a third round of pulse-dose glucocorticoids. Rituximab was added to the cyclophosphamide, IVIG and glucocorticoids—finally leading to clinical remission. A slow glucocorticoid taper was started, cyclophosphamide was transitioned to a maintenance dose of mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab and IVIG were continued. IVIG was discontinued a few years later due to a severe adverse reaction.

Over the past few years, patient 2 has had recurrent episodes of visual disturbances, with evidence of vascular leakage on ophthalmologic exam. His hearing loss has remained stable and persistent and is managed with the support of hearing aids. He has no residual neurological or cognitive defects. Despite his medical challenges, he obtained his bachelor’s degree and now works as a software developer. He was recently married.

Despite similarities in clinical presentation, these patients had distinct clinical courses. Patient 1 had a favorable response to initial immunosuppressive therapy, ultimately leading to prolonged drug-free remission. Patient 2 suffered refractory disease with persistent episodes of visual disturbances, requiring ongoing aggressive immunosuppressive treatment.

Susac Syndrome

Susac syndrome is an immune-mediated, occlusive microvascular endotheliopathy of the brain, inner ear and retina. John Susac, MD, was the neurologist who first described the syndrome in 1975.1 Since 2021, more than 450 cases of Susac syndrome have been published worldwide. Epidemiologic data are limited because the disease remains underdiagnosed and delays to diagnosis are common.

Susac syndrome affects the brain, retina and inner ear, primarily affecting young adults. It’s manifested by a triad of encephalopathy, sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss and branch retinal artery occlusions. Brain MRIs typically show disseminated lesions that involve the corpus callosum.2

Dr. Furer

“Prompt recognition of an underlying immune-mediated and/or inflammatory disease is important [because] early diagnosis and treatment prevent permanent disability,” said Dr. Furer. “Recognition of specific patterns of involvement can serve as diagnostic clues.”

Differential Diagnoses

After ruling out infection, malignancy and toxic etiologies, the differential diagnoses of brain, ear, eye syndromes fall into three categories:

- Demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder;

- Rheumatic inflammatory systemic diseases, such as SLE, Behçet disease and sarcoid; and

- Rare diseases that stand alone, such as Susac syndrome, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and Cogan syndrome.

MS is the most common immune-mediated, inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). It can cause visual symptoms, with 50% of patients having optic neuritis. It may cause sudden unilateral, sensorineural hearing loss in 4% of patients and can be followed by bilateral sensorineural hearing loss.3

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder is an inflammatory condition of the CNS characterized by severe, immune-mediated demyelination and axonal damage, predominantly targeting the optic nerves and multiple segments of the spinal cord. Bilateral optic neuritis can cause severe visual loss, and sudden unilateral or bilateral, sensorineural hearing loss is more common than in MS due to cochlear nuclei lesions.4

“Corpus callosum lesions can occur in both MS and NMOSD,” said Dr. Furer. “So it’s important to consider these [conditions] in the differential diagnosis. Lesions have a different radiographic appearance, and radiology can help differentiate them from Susac syndrome.”

Neuropsychiatric SLE can have a variable presentation. In the eyes, it may cause dry eye, corneal erosions, ulcerative keratitis, uveitis or lupus retinopathy (i.e., extensive arteriolar occlusions with bilateral macular infarctions). Unilateral or bilateral sensorineural hearing loss may occur too.5

“It’s important to note that neuropsychiatric SLE is radiographically indistinguishable from the appearance of many other etiologies,” said Dr. Furer.

Behçet’s disease involves the eyes in 25–75% of patients and progresses to blindness if untreated. Uveitis is the dominant ophthalmologic manifestation of disease, but hypopyon, retinal vasculitis, vascular occlusion and optic neuritis may also occur. Sensorineural hearing loss occurs in 20–30% of patients and is typically mild.6

Neurosarcoidosis affects up to 15% of patients with sarcoidosis. Eye involvement occurs in 25–60% of patients and may manifest as conjunctivitis, anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, orbital inflammation, lacrimal gland enlargement or optic neuropathy. Sensorineural hearing loss is rare, but may also occur.7

When to Consider Susac Syndrome?

Susac syndrome should come to mind when a patient has a triad of encephalopathy (CNS dysfunction), visual loss (branch retinal artery occlusions) and sensorineural hearing loss.

CNS dysfunction: “New-onset headache can hint at Susac syndrome, although this [symptom] is nonspecific. Focal neurological signs, behavioral changes and encephalopathy should prompt consideration of this diagnosis,” Dr. Furer said.

Typical CNS findings include cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis (50% of patients), elevated protein (80% of patients) and multiple hyperintense lesions on brain MRI with pathognomonic snowball lesions in the corpus callosum, as well as other regions.8

Visual loss: Branch retinal artery occlusions may be asymptomatic or present as a loss of visual acuity, flashing or blindness.

“Fundoscopy, optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography are key clinical and diagnostic tools that we should use in every patient considered for Susac syndrome. Branch retinal artery occlusions are found in 99% of patients, so fluorescein angiography is an obligatory test, even in the absence of visual symptoms,” Dr. Furer said.

Sensorineural hearing loss may present as hearing loss, tinnitus and/or vertigo. Dr. Furer said, “Audiogram should be performed in all patients, even in the absence of symptoms.”

A Challenging Diagnosis

Susac syndrome has a wide range of clinical variability, especially when it comes to neurologic symptoms. The full clinical triad is rare at disease onset and seen in less than 20% of patients, but it does develop in 85% of patients during the disease course. The natural history of the disease is also variable. It’s monocyclic in 50% of patients, polycyclic in 40%, and 10% of patients have a chronic-continuous form.

“All these factors lead to diagnostic delay and potential irreversible damage that we all want to prevent,” Dr. Furer said.

Diagnostic criteria for Susac syndrome were published by the European Susac Consortium (EuSaC) in 2016.9

Treatment

Treatment approaches for Susac syndrome are informed by the severity of CNS involvement, which is defined by clinical features, brain MRI findings, cerebrospinal fluid findings and response to treatment. Treatment is based on expert opinion due to a lack of randomized controlled trial data.8,10

“Early aggressive intensive immunosuppressive treatment is the cornerstone,” said Dr. Furer, “and is associated with better outcomes based on longitudinal follow-up of a cohort of patients with Susac syndrome.”

The combination of immunosuppression is dictated by the severity of CNS involvement. Treatment duration depends on clinical course and response to treatment, but typically lasts at least two years.

Key Takeaways

Dr. Furer wrapped up her talk with the most salient points for a practicing rheumatologist to know:

- Susac symdrome is an autoimmune endotheliopathy targeting the brain, retina and cochlea. CNS involvement is the most common presenting symptom;

- Brain MRI, fluorescein angiography and audiogram are required for diagnosis in all patients suspected of having Susac syndrome;

- Treatment approaches depend on CNS disease severity. Early aggressive immunosuppressive therapy is paramount in severe cases, followed by a slow taper; and

- Multi-disciplinary collaboration is required for optimal management.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is the executive editor of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. As a clinician educator, she practices telerheumatology and writes for both medical and lay audiences.

References

- Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979 Mar;29(3):313–316.

- Marrodan M, Fiol MP, Correale J. Susac syndrome: Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment. Brain. 2022 Apr 29;145(3):858–871.

- Peyvandi A, Naghibzadeh B, Roozbahany NA. Neuro-otologic manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Arch Iran Med. 2010 May;13(3):188–192.

- Tugizova M, Feng H, Tomczak A, et al. Case series: Hearing loss in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020 Jun:41:102032.

- Kastanioudakis I, Ziavra N, Voulgari PV, et al. Ear involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: A comparative study. J Laryngol Otol. 2002 Feb;116(2):103–107.

- Webb CJ, Moots RJ, Swift AC. Ear, nose and throat manifestations of Behçet’s disease: A review. J Laryngol Otol. 2008 Dec;122(12):1279–1283.

- Cereceda-Monteoliva N, Rouhani MJ, Maughan EF, et al. Sarcoidosis of the ear, nose and throat: A review of the literature. Clin Otolaryngol. 2021 Sep;46(5):935–940.

- Rennebohm RM, Asdaghi N, Srivastava S, et al. Guidelines for treatment of Susac syndrome—an update. Int J Stroke. 2020 Jul;15(5):484-494.

- Kleffner I, Dörr J, Ringelstein M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for Susac syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016 Dec;87(12):1287–1295.

- Bose S, Papathanasiou A, Karkhanis S, et al. Susac syndrome: Neurological update (clinical features, long-term observational follow-up and management of sixteen patients). J Neurol. 2023 Dec;270(12):6193–6206.