Scleroderma renal crisis is a true medical emergency in rheumatology, one that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. Here, we review the historic introduction of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in this context, and highlight management and key questions moving forward.

Background

Awareness of renal disease in scleroderma dates back many years. The revered physician William Osler noted in 1892 that patients with scleroderma were “apt to succumb to pulmonary complaints or to nephritis.”1 Awareness of the condition increased in 1952 with a case report of three patients appearing in The Lancet.2 More case reports and limited reviews of the topic were published, but the disease’s causes, incidence and disease course were not well characterized.

Once such case report from 1960 noted the aggressive, fulminant presentation of scleroderma renal crisis: “The hypertension is rapidly followed by retinopathy, cardiac failure, convulsions, profound oliguria and uraemia. The progression of the disease from the appearance of hypertension to death is usually so rapid that there is little time for clinical evidence of renal disease to become fully apparent.”1 The disease was almost always fatal, until the first reported successful nephrectomy followed by renal transplant in 1970.3

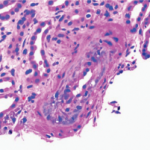

In 1974, a seminal paper on scleroderma and renal disease appeared, a clinicopathological review of 210 patients with scleroderma seen over the previous 20 years. The detailed 46-page report included thorough case studies, clinical evaluations, renal blood flow measures, such lab analyses as renin, treatment outcomes and information about renal histopathology. The writers also hypothesized about the pathogenic role of renin release in scleroderma renal crisis.4

The research team, headed by E. Carwile LeRoy, MD, found evidence of some type of renal involvement in 45% of scleroderma patients, lumping together such markers as proteinuria, hypertension and azotemia. Some of these patients had only low-level, asymptomatic renal disease. Critically, the team reported that the syndrome of malignant hypertension (scleroderma renal crisis), characterized by rapidly progressive renal damage, occurred in 7% of their patients and was fatal in 12 out of these 15 cases. For all patients, scleroderma renal crisis was the leading cause of death.4

Dr. Whitman

Hendricks H. Whitman III, MD, FACP, an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, notes, “In those days, if scleroderma patients became hypertensive and their kidneys began to be damaged, that’s what actually killed them. Scleroderma patients had about a 50% mortality in 10 years. And almost all of them died from hypertension or renal failure.”

A few scattered reports appeared of successful aggressive medical management of scleroderma renal crisis with such agents as minoxidil, but the prognosis was grim.5,6 Virginia D. Steen, MD, a professor and chief of the Division of Rheumatology of the Department of Medicine at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., recounts, “Even when I was a fellow, we kept trying all these kinds of medications, and nothing did anything. I remember vividly as a student, being in a conference where they decided to do a bilateral nephrectomy on a young woman as the only way to save her life.”

Dr. Whitman recalls how patients with scleroderma and baseline hypertension were managed then. “We didn’t know any better in those days, so we’d give them a diuretic, which would actually make things worse rather than better, or we’d give them a beta blocker, and that would be really bad for their Raynaud’s phenomenon.” Some rheumatologists observed that scleroderma renal crisis was sometimes triggered by diuretic therapy initiated to control a baseline high blood pressure.6