Scleroderma renal crisis is a true medical emergency in rheumatology, one that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. Here, we review the historic introduction of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in this context, and highlight management and key questions moving forward.

Background

Awareness of renal disease in scleroderma dates back many years. The revered physician William Osler noted in 1892 that patients with scleroderma were “apt to succumb to pulmonary complaints or to nephritis.”1 Awareness of the condition increased in 1952 with a case report of three patients appearing in The Lancet.2 More case reports and limited reviews of the topic were published, but the disease’s causes, incidence and disease course were not well characterized.

Once such case report from 1960 noted the aggressive, fulminant presentation of scleroderma renal crisis: “The hypertension is rapidly followed by retinopathy, cardiac failure, convulsions, profound oliguria and uraemia. The progression of the disease from the appearance of hypertension to death is usually so rapid that there is little time for clinical evidence of renal disease to become fully apparent.”1 The disease was almost always fatal, until the first reported successful nephrectomy followed by renal transplant in 1970.3

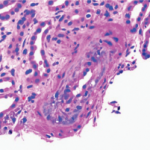

In 1974, a seminal paper on scleroderma and renal disease appeared, a clinicopathological review of 210 patients with scleroderma seen over the previous 20 years. The detailed 46-page report included thorough case studies, clinical evaluations, renal blood flow measures, such lab analyses as renin, treatment outcomes and information about renal histopathology. The writers also hypothesized about the pathogenic role of renin release in scleroderma renal crisis.4

The research team, headed by E. Carwile LeRoy, MD, found evidence of some type of renal involvement in 45% of scleroderma patients, lumping together such markers as proteinuria, hypertension and azotemia. Some of these patients had only low-level, asymptomatic renal disease. Critically, the team reported that the syndrome of malignant hypertension (scleroderma renal crisis), characterized by rapidly progressive renal damage, occurred in 7% of their patients and was fatal in 12 out of these 15 cases. For all patients, scleroderma renal crisis was the leading cause of death.4

Dr. Whitman

Hendricks H. Whitman III, MD, FACP, an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, notes, “In those days, if scleroderma patients became hypertensive and their kidneys began to be damaged, that’s what actually killed them. Scleroderma patients had about a 50% mortality in 10 years. And almost all of them died from hypertension or renal failure.”

A few scattered reports appeared of successful aggressive medical management of scleroderma renal crisis with such agents as minoxidil, but the prognosis was grim.5,6 Virginia D. Steen, MD, a professor and chief of the Division of Rheumatology of the Department of Medicine at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., recounts, “Even when I was a fellow, we kept trying all these kinds of medications, and nothing did anything. I remember vividly as a student, being in a conference where they decided to do a bilateral nephrectomy on a young woman as the only way to save her life.”

Dr. Whitman recalls how patients with scleroderma and baseline hypertension were managed then. “We didn’t know any better in those days, so we’d give them a diuretic, which would actually make things worse rather than better, or we’d give them a beta blocker, and that would be really bad for their Raynaud’s phenomenon.” Some rheumatologists observed that scleroderma renal crisis was sometimes triggered by diuretic therapy initiated to control a baseline high blood pressure.6

Diagnosing scleroderma renal crisis can sometimes be a challenge, particularly if it is the first presenting symptom of scleroderma.

Entrance of the Ace Inhibitors

When the kidney senses it isn’t getting enough blood, it secretes renin, which acts on the protein angiotensinogen to produce angiotensin I. In the 1950s, researchers discovered the enzyme that could transform angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a powerful vasoconstrictor.7 Dr. Whitman explains, “All the blood vessels in your body start constricting, and let’s say you have a finite amount of salt and water and blood circulating. Your blood vessels go into spasms, and your blood pressure shoots up.”

This angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) eventually attracted attention as a drug target. This eventually led to the breakthrough development of the first successful oral ACE inhibitor, captopril, in the 1970s, which displayed a clear antihypertensive effect.7

John H. Laragh, MD, was one of the pioneers in the study of the renin-angiotensin system and hypertension. He and others were exploring the role of ACE inhibitors in the potential treatment of essential hypertension at the Hypertension-Cardiovascular Center at the New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Center.8

Researchers had hypothesized that elevated renin might play a pathological role in scleroderma renal crisis, based on animal studies and some earlier case reports. Dr. Steen says, “The ACE inhibitors were a brand-new class of medications. John Laragh was working on it for hypertension, and by around that time they knew that scleroderma was a renin-driven hypertension type of thing, so it was natural to try it.”

In 1977, Dr. Laragh and his colleagues published “Reversal of Vascular and Renal Crises of Scleroderma by Oral Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Blockade,” the first case report to describe the effects of an ACE inhibitor on scleroderma renal crisis.6 It detailed the stories of two scleroderma patients who displayed dramatic reversal of their renal crisis in response to captopril (SQ 14225), which had not yet been released publicly. The authors proposed that captopril, if used at the first sign of scleroderma renal crisis, might provide a powerful tool to protect against renin-induced vasoconstriction and so prevent life-threatening vascular damage.

Dr. Steen

Dr. Steen was pursuing a fellowship in rheumatology at the University of Pittsburgh, where she worked under the esteemed rheumatologist Gerald P. Rodnan, MD. She recalls that Dr. Rodnan was in communication with William A. D’Angelo, MD, a co-author and one of the physicians collaborating with Dr. Laragh.

As a fellow, Dr. Steen herself treated “patient 2,” a 25-year-old student with newly diagnosed severe scleroderma. She recounts that he and his family were in Florida over the holidays. “We got a call that he was in the emergency room with a blood pressure of 220 over 120. Dr. Rodnan had just found out about this drug and its availability, and he made it all happen.” They arranged to have him flown back to New York City for treatment. She adds, “We literally saved his life with this drug.”

Other reports soon followed. In 1981, another case study out of University of California, Los Angeles, described four patients with scleroderma renal crisis successfully treated with captopril.9 Another key study came out in 1982 from Dr. Laragh’s group working in collaboration with Dr. LeRoy: Variable Response to Oral Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Blockade in Hypertensive Scleroderma Patients.10

Dr. Whitman, the study’s first author, first began working with Dr. Laragh during a second-year resident elective at the Hypertension Center. Dr. Laragh asked his resident to study the response to captopril in his patients with scleroderma who had hypertension. He began treating these patients shortly before captopril’s FDA approval for essential hypertension.

Dr. Whitman analyzed seven patients with scleroderma renal crisis as well as a group of five patients with hypertensive urgency. Blockade of the angiotensin system effectively controlled blood pressure in all the patients. Five out of the seven patients with scleroderma renal crisis progressed to renal failure despite this, suggesting that their renal function had already been too compromised.10

Dr. Whitman explains, “If we didn’t get them on the captopril before their serum creatinine began to climb very rapidly, specifically a value about 2.5, they went ahead and went into renal failure. But if we gave them the medication before their serum creatinine got worse, we were able to stop them from getting malignant hypertension.”

Dr. Whitman notes that although this article received a lot of publicity, many other centers around the country were working on the topic, particularly the University of Pittsburgh. He adds, “We just happened to get more patients faster because we were working not only out of a rheumatology group of patients but also a hypertension center that was well known and run by Dr. Laragh, who was a very famous guy.”

Dr. Steen recounts that ACE inhibitors for scleroderma renal crisis moved into practice rapidly. Dr. Steen, Dr. Rodnan, Dr. D’Angelo and Dr. LeRoy planned to do a trial comparing captopril with minoxidil. She adds, “Then the drug came out, and nobody would enter anybody into the study, because people were finding out that the drug worked so miraculously that they wouldn’t even consider doing a controlled trial with another drug. You could give them this drug, and it was so dramatic—you could just see it. Particularly because, before then, almost everyone died.”

Follow-Up Studies

Follow-up studies by Dr. Steen and others proved that ACE inhibitors were a lifesaving intervention. Dr. Steen et al. reported on the experience of 108 patients who had scleroderma renal crisis between 1972 and 1985. The one-year survival after scleroderma renal crisis was 76% in patients who had taken ACE inhibitors and only 15% in those who had not.11 Though some patients still died and other required permanent dialysis, renal crisis could usually be effectively managed when treated early and aggressively with ACE inhibitors. More than half of the patients who initially required dialysis were able to come off it if they continued taking ACE inhibitors while their kidneys healed.

Currently, early intervention with ACE inhibitors is the standard of care at first sign of scleroderma renal crisis. However, other applications of ACE inhibitors in scleroderma patients are not as clear. Researchers also explored the role of these drugs as agents to prevent scleroderma renal crisis. By this time, ACE inhibitors were already being prescribed as a preventative for diabetic kidney disease.

However, some studies suggested that ACE inhibitors used as a preventative for scleroderma renal crisis might worsen outcomes, particularly if given to patients with normal blood pressure.12 This created some confusion in the field.

Some researchers expressed concern that ACE inhibitors might mask hypertension and lead to delayed diagnosis of renal crisis.13 Dr. Steen speculates that the chronic administration of an ACE inhibitor might have changed the disease course in some of these patients. She says, “They were presenting with creatinines that were 3 and 4 instead of 1 or 2, and by that time they already had chronic kidney disease.”

Some practitioners still prescribe ACE inhibitors as first-line agents for managing essential hypertension in scleroderma patients if they are not in a high-risk group. In contrast, Dr. Whitman notes, “As a rule of thumb, we don’t give diuretics to scleroderma patients unless we are forced to—for example, if they have heart failure—because you could theoretically trigger the renin-angiotensin system and scleroderma renal crisis.” He adds that he might start a patient out on calcium channel blocker, which are particularly good for Raynaud’s symptoms. “But if the blood pressure kept going up, we might give them an ACE inhibitor or an [angiotensin II receptor blocker].”

Scientists still have questions about renal disease in settings other than scleroderma renal crisis. Some patients have essential hypertension unrelated to scleroderma, or they have renal disease from other medical conditions. Additionally, many patients with scleroderma have subtle renal abnormalities, such as proteinuria and involvement of renal vessels, though these changes seem not to predict the development of scleroderma renal crisis.12 Dr. Steen points out that although some might develop mild renal insufficiency, very few patients go on to develop renal failure unless they experience a true scleroderma renal crisis.

Risk Factors

Although the exact incidence is unclear, it’s now thought that scleroderma renal crisis affects around 2–15% of scleroderma patients, with typical onset within the first three to five years after diagnosis.12

Dr. Steen and other researchers have identified risk factors for scleroderma renal crisis. These include high-dose steroids, worsening skin symptoms, positivity for anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies and new anemia or cardiac events. Scleroderma renal crisis is also much more common in patients with the diffuse cutaneous form of the disease.12

The presence of one or more of these risk factors can provide diagnostic clues about scleroderma renal crisis. Patients usually present with malignant hypertension but may also be normotensive (though with increased blood pressure from their personal baseline). Patients have rising creatinine levels, low urine output, and often have microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.12

Diagnosing scleroderma renal crisis can sometimes be a challenge, particularly if it is the first presenting symptom of scleroderma. It is sometimes misdiagnosed as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, as hemolytic uremic syndrome or as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis is another potential cause of acute renal failure in a patient with scleroderma, and it requires different treatment.12 But Dr. Steen notes, “Even if there is another possible diagnosis, I feel that if they have scleroderma, they should be treated with an ACE inhibitor until another diagnosis is confirmed, because it is both potentially kidney saving and lifesaving.”

Current management of scleroderma renal crisis requires early and aggressive intervention with ACE inhibitors and, if needed, with other medications, such as calcium channel blockers, and dialysis. Beta blockers should be avoided, because they exacerbate Raynaud’s phenomenon. If renal function has not returned within a year of continued ACE inhibitors, renal transplantation is the next step.12

Outcomes & Ongoing Research

Although the introduction of ACE inhibitors dramatically and positively changed outcomes of scleroderma renal crisis, some patients still do die or require long-term dialysis. In a study of 145 patients with scleroderma renal crisis treated with inhibitors, 38% of patients had poor outcomes.14 Older, debilitated patients and those with congestive heart failure also tend to do worse, as do patients presenting with greater than 3mg/dl creatinine.15 Dr. Steen explains, “Some of them don’t do well because they weren’t diagnosed promptly and accurately, and some don’t do well because the disease is so resistant.”

Dr. Steen emphasizes the need for both physician and patient education. Physicians need to be on the lookout for scleroderma renal crisis and recognize it as an urgent situation that requires immediate treatment. Particularly for high risk groups, it’s critical that patients understand the potential symptoms of high blood pressure, monitor their pressure at home and seek immediate treatment when necessary.

Since the advent of ACE inhibitors and the improved survival of renal crisis, lung involvement with pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis has surpassed kidney disease as the leading cause of death in scleroderma patients.16 Yet scleroderma renal crisis still remains a major risk factor for mortality in scleroderma patients. After the initial improvement with introduction of the ACE inhibitors in the 1980s, the prognosis has not changed much.

Research continues for agents that might improve outcomes. Dr. Steen points out that it is difficult to perform good clinical trials of scleroderma renal crisis because the disease manifests so quickly. Researchers are currently exploring whether the addition of endothelin-1 receptor blocker medications—now used to treat digital ulcers and pulmonary hypertension in scleroderma—might also improve outcomes in scleroderma renal crisis when used in addition to ACE inhibitors.17

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Bourne FM, Howell DA, Root HS. Renal and cerebral scleroderma. Can Med Assoc J. 1960 Apr 23;82(17):881–886.

- Moore HC, Sheehan HL. The kidney of scleroderma. Lancet. 1952 Jan 12;1(6698):68–70.

- Richardson JA. Hemodialysis and kidney transplantation for renal failure from scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1973 Mar-Apr;16(2):265–271.

- Cannon PJ, Hassar M, Case DB, et al. The relationship of hypertension and renal failure in scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis) to structural and functional abnormalities of the renal cortical circulation. Medicine (Baltimore). 1974 Jan;53(1):1–46.

- Moorthy AV, Wu MJ, Beirne GJ, et al. Control of hypertension with acute renal failure in scleroderma without nephrectomy. Lancet. 1978 Mar11;1(8063):563–564.

- Lopez-Ovejero JA, Saal SD, D’Angelo WA, et al. Reversal of vascular and renal crises of scleroderma by oral angiotensin-converting-enzyme blockade. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 21;300(25):1417–1419.

- Bryan J. From snake venom to ACE inhibitor—the discovery and rise of captopril. Pharmaceutical Journal. 17 April 2009.

- Sealey JE. John H. Laragh, MD: Clinician-scientist. Am J Hypertens. 2014 Aug;27(8):1019–1023.

- Zawada ET Jr, Clements PJ, Furst DA, et al. Clinical course of patients with scleroderma renal crisis treated with captopril. Nephron. 1981;27(2):74–78.

- Whitman HH 3rd, Case DB, Laragh JH, et al. Variable response to oral angiotensin-converting-enzyme blockade in hypertensive scleroderma patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1982 Mar;25(3):241–248.

- Steen VD, Costantino JP, Shapiro AP, et al. Outcome of renal crisis in systemic sclerosis: relation to availability of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Sep 1;113(5):352–357.

- Woodworth TG, Suliman YA, Li W, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis and renal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016 Nov;12(11):678–691.

- Zanatta E, Polito P, Favaro M, et al. Therapy of scleroderma renal crisis: State of the art. Autoimmun Rev. 2018 Sep;17(9):882–889.

- Steen VD, Medsger TA Jr. Long-term outcomes of scleroderma renal crisis. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Oct 17;133(8):600–603.

- Steen VD. Kidney involvement in systemic sclerosis. Presse Med. 2014 Oct;43(10 Pt 2):e305–314.

- Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jul;66(7):940–944.

- Penn H, Quillinan N, Khan K, et al. Targeting the endothelin axis in scleroderma renal crisis: Rationale and feasibility. QJM. 2013 Sep;106(9):839–848.