anttoniart / shutterstock.com

Late-night gatherings; long hours of avid discussion weighing the merits of resolution quality, light, hues and tones; and camaraderie among members forged through a shared interest in maintaining the highest fidelity to their craft and profession—these are among the vivid memories of those who participated in the early years of building what is today known as the ACR Image Library.

Currently housing more than 2,000 images, the ACR Image Library has served for years as a major repository of high-quality images of rheumatic diseases used by rheumatologists and others around the world. Every year new images are added to the online collection, making this an up-to-date dynamic resource for teaching and education.

As with all successful endeavors, laying the foundation for the Image Library and its sustaining service to the field of rheumatology and other clinical areas took years of hard work, adherence to rigorous standards and a strong vision of the educational excellence offered by teaching through seeing.

The figure on the June 2020 Arthritis & Rheumatology cover, from the ACR Image Library, is a photomicrograph showing birefringent, needle-shaped monosodium urate crystals from the joint fluid of a patient with gout, as demonstrated with compensated polarized light microscopy. This image illustrates the enduring educational value of the Image Library, first conceived in 1956, nearly 65 years ago.

The Image Library evolved alongside evolutions in the organization of rheumatology itself. Several name changes occurred over the past near century. In 1927, the American Committee to Control Rheumatism was formed, and in 1937 it was renamed the American Rheumatism Association (ARA). It was under the ARA in 1956 that the first iteration of the Image Library emerged as a modest collection of pathology slides.

The Arthritis and Rheumatism Foundation incorporated in 1948 and, in 1965, changed its name to the Arthritis Foundation, at which time the ARA became the professional section of the Arthritis Foundation. In 1985, the ARA separated from the Arthritis Foundation, and in 1988 the ARA changed its name to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). The Image Library was continued under the auspices of the ACR.

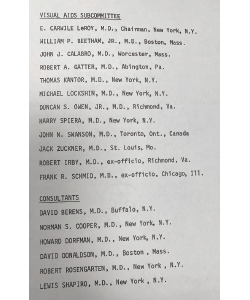

In 1958, the library was expanded to include clinical images of rheumatic diseases and became known as the Clinical Slide Collection on the Rheumatic Diseases. In 1972, the first collection of clinical images was published. The committee then overseeing the collection was the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee. Today, the Image Library Subcommittee, under the ACR’s Committee on Education, continues the Image Library work.

Early Contributors

Early members of the subcommittee who contributed images to the collection included rheumatologists William Beetham Jr., John Calabro, Robert Gatter, E. Carwile Leroy, Currier McEwen, Michael Lockshin and Jack Zuckner. Other major contributors included pathologists and radiologists, notably David Berens, Norman Cooper and Howard Dorfman. Robert Rosengarten, a rheumatologist with a large private practice on Long Island, provided most of the early submissions from his personal large slide collection.

An early roster of the Visual Aids Subcommittee.

The original image collection was distributed in slide format with this publication.

To ensure the collection achieved the highest quality possible, professional photographers, Lester and Sylvia Bergman, were hired to create images with the precision and clarity needed to do what these collections were built to do—educate rheumatologists about the range of rheumatic diseases seen in the clinic daily.

Jane Diamond, managing editor of Arthritis & Rheumatology, actively contributed as project manager through many iterations of the collection.

The fertile ground on which this foundation was built is evident in the next iteration of the image collection. Using the vast changes and powers of technology, the image collection went digital and moved online in 2009.

Out of the Past

Numerous people helped build the Image Library as it evolved to its current form. A few of the contributors recently talked with The Rheumatologist about the contributions they made:

Michael D. Lockshin, MD, is now the director of the Barbara Volcker Center, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a professor of medicine and obstetrics-gynecology, Weill Cornell Medicine. As a rheumatology fellow at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, New York, in 1968–70, Dr. Lockshin would often bring his camera to the clinical wards to photograph patients. His behavior caught the notice of E. Carwile Leroy, MD, soon to be department chair, who asked Dr. Lockshin in 1968 to join the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee.

Michael D. Lockshin, MD, is now the director of the Barbara Volcker Center, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a professor of medicine and obstetrics-gynecology, Weill Cornell Medicine. As a rheumatology fellow at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, New York, in 1968–70, Dr. Lockshin would often bring his camera to the clinical wards to photograph patients. His behavior caught the notice of E. Carwile Leroy, MD, soon to be department chair, who asked Dr. Lockshin in 1968 to join the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee.

‘By judicious cropping, tint & light control, & advice, the Bergmans, in those pre-Photoshop days, did amazing things with very marginal material.’ —Dr. Lockshin

Laying the foundation for the Image Library & its sustaining service to the field of rheumatology & other clinical areas took years of hard work, adherence to rigorous standards & a strong vision.

At that time, rheumatology was just on the cusp of being formally identified as a subspecialty of medicine, which occurred in 1972. “Because rheumatology was new and because relatively rare abnormalities in rheumatologic diseases are highly visible, the powers-that-be felt that a slide collection showing the abnormalities would be a valuable teaching tool,” said Dr. Lockshin, who chaired the subcommittee from 1972–75.

In 1972, the first clinical slide collection was assembled. The collection comprised 240 35 mm slides chosen from thousands submitted by 105 physicians. Of these 240 original slides, 191 remain in the Image Library—“a 50-year survival rate of 79%!” notes Dr. Lockshin. At a cost of just under $10,000, the Clinical Slide Collection on the Rheumatic Diseases was published as a syllabus by the Arthritis Foundation.

This picture exemplifies the high visual quality required in the slide collection: clean background, focus on the specific problem, no distracting features like bandages, etc. In this case, the swan-neck deformity is very clearly illustrated and is the only abnormal point in this photograph. (One could argue that a small degree of MCP synovitis is present.)

This is one of the very few slides in the first collection that allowed two images. In this case it demonstrates a fortunately now rare manifestation of very severe psoriatic arthritis mutilans, showing in identical poses what the hand looks like to a clinician and the very severe destructive disease seen radiologically. (In the original slide, the radiograph was much clearer. The slide was submitted by E. Carwile LeRoy.)

Dr. Lockshin recalls spending long hours with other committee members debating the merits of slides and working with the Bergmans to make the collection as visually attractive and informative as possible. He praised the Bergmans for their esthetic sense—eliminating extraneous details in photos, such as bedclothing and patient jewelry, to focus on the teaching point—as well as their careful attention to light distribution and tint.

Fulfilling the adage that no good deed goes unpunished—but certainly makes a good story—Dr. Lockshin recalls being “rewarded” for his role in assembling the 1972 collection by being asked to present the collection formally during the 1973 International League Against Rheumatism (ILAR) meeting in Kyoto, Japan. Circumstances led to the ACR financing his travel by designating him the official travel guide to the other Americans traveling to the meeting.

“One of the travelers (a prominent rheumatologist whom I shall not name) decided, on his own, that my duties included personally picking up his very large, very heavy, aluminum suitcase from the luggage belt and delivering it to the transportation truck and from there to the hotel,” says Dr. Lockshin, who remembers the unnamed person smiling as he struggled to lift the luggage. The result? Dr. Lockshin ended up on the floor in his hotel room with “exquisite back pain.” Dr. Lockshin adds, “Forty-seven years later I remember this, including his maddening smile. I didn’t pick up his luggage when we returned to New York.”

Joseph Croft, MD, clinical professor of rheumatology at Georgetown University Medical Center and past president of the ACR, overlapped with Dr. Lockshin’s term on the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee from 1974–88. Dr. Croft served as committee chair from 1975–82.

Joseph Croft, MD, clinical professor of rheumatology at Georgetown University Medical Center and past president of the ACR, overlapped with Dr. Lockshin’s term on the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee from 1974–88. Dr. Croft served as committee chair from 1975–82.

During his tenure, Dr. Croft led major revisions to the Clinical Slide Collection that culminated in the publication of a second edition in 1981, called the Revised Clinical Slide Collection on the Rheumatic Diseases. He remembers fondly the long hours spent with the Bergmans in dark rooms using Kodak Carousel projectors to review Kodachrome 35 mm color slides for the smallest of details in background colors, content accuracy and avoidance of visual distractions to ensure the highest quality.

“We spent nights in dark rooms going over hundreds of slides, changing bulbs in the projector to see what light worked to obtain the best reproductions,” he recalls. “We were all astonished at what just subtle changes in light could [do].”

‘The Image Library has been the sine qua non of the commitment & effort of the ACR to produce important educational materials.’ —Dr. Croft

Dr. Croft also recalls spending numerous nights and weekends at home preparing the final edits for the revised collection. Of 2,000 submitted new slides, 40 were selected to replace some of the clinical and radiographic topics of the first collection, and 93 were chosen as additions. Nearly half of the new slides depicted diseases with rheumatic manifestations not included in the previous syllabus.

Such attention to detail and visual artistry led to a collection that became known outside the ARA. In 1982, the association was approached by an international publishing company that wanted the rights to publish the collection. Dr. Croft spent early January in London discussing the details with the publishing representatives, but when he returned and reported to the association board, it was decided “wisely, in retrospect, to maintain this activity in house as a proprietary product,” he says.

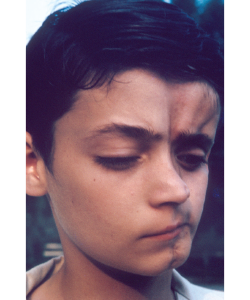

This was one of the very few slides in the first collection that included a distracting background. It was allowed in the collection only because the condition was so rare that no other slides were available (then called en coup de sabre lesion of linear scleroderma; today it would be described separately as Parry-Romberg syndrome, a distinction not made in the early 1970s). The photograph was submitted by Bernard Rogoff.

This photograph of a woman with dermatomyositis was included not only because it illustrates the rash and periorbital erythema, but also as an inside joke: John Decker, who closely advised the committee, rejected many slides because they showed periorbital edema, which he insisted was not necessary for a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. The committee challenged him to find a slide that did not show periorbital edema, and this is the best he could produce. Case closed.

Three years later, Barbara Ansell, MD, a pioneer in rheumatology and founder of pediatric rheumatology, wrote a review of the second edition that was published in the Journal of Clinical Pathology, calling it “well thought out and presented; in particular the accompanying photographs and descriptions are excellent.”

Sidney Block, MD, a rheumatologist whose private practice encompasses northern and eastern Maine, chaired the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee between 1982 and 1989. A tradition started during his tenure may be what many people today know best about the Image Library—the slide competition. Initiated in 1983, the annual contest was designed to expand the image collection by encouraging submissions from the entire rheumatology community. Prior to this, slides had been submitted primarily by committee members who either took the photographs themselves or sought them from other sources. There was always one member from the Mayo Clinic who was able to tap into that institution’s collection.

Sidney Block, MD, a rheumatologist whose private practice encompasses northern and eastern Maine, chaired the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee between 1982 and 1989. A tradition started during his tenure may be what many people today know best about the Image Library—the slide competition. Initiated in 1983, the annual contest was designed to expand the image collection by encouraging submissions from the entire rheumatology community. Prior to this, slides had been submitted primarily by committee members who either took the photographs themselves or sought them from other sources. There was always one member from the Mayo Clinic who was able to tap into that institution’s collection.

‘I learned more from being a member of the Audiovisual Aids Subcommittee than I did from anyone else.’ —Dr. Block

The contest led to a rapid and marked expansion of the collection. A half dozen of the submissions were chosen each year, based on their particular importance or how well they demonstrated a disease. These designated winners were presented during the business meeting at the annual meeting and then published in Arthritis & Rheumatism. “The contest was wildly successful,” says Dr. Block.

Probably remembered even more than the presentation of the winners were the so-called losers, says Dr. Block. Created as a takeoff on an annual and very unofficial affair at the Johns Hopkins Medical School (where Dr. Block did his medical training) in which students made fun of their professors, the committee invented slides supposedly attributed to notable officers and members of the association.

One example was a staged slide of a drunkard, face down on a bar holding high and at a very peculiar angle a can of Old Milwaukee beer, described at the business meeting as an example of “the genesis of the Old Milwaukee Shoulder, submitted by Old Dan McCarty” (who first described the Milwaukee shoulder, a destructive shoulder arthropathy due to deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals). The loser presentations were so popular that the event became known as Everybody Loves a Loser.

Eric Matteson, MD, professor emeritus of rheumatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., who took over as chair of the committee from 1995–2000, acknowledges the major contributions of his colleague William Ginsberg, MD, who provided many high-quality slides for the collection.

Eric Matteson, MD, professor emeritus of rheumatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., who took over as chair of the committee from 1995–2000, acknowledges the major contributions of his colleague William Ginsberg, MD, who provided many high-quality slides for the collection.

Dr. Matteson describes a number of changes to the image collection under his guidance, notably the transformation of what had become a three-volume slide set to a digitized format sold as CD-ROMs.

‘One of the really important aspects of the Image Library may be the continual evolution of our understanding of our diseases … how bad some of these diseases are, how they affect people—the enormity of rheumatic disease.’ —Dr. Matteson

Further changes to the collection reflected the technological advances of the time, such as the creation of a radiology supplement. New tools, such as magnetic resonance imaging, were featured to demonstrate joint erosions, ligament or meniscal tears, and inflammation. Also enhanced was a complementary slide collection for the Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (now the Association of Rheumatology Professionals) that included valuable teaching slides relevant to musculoskeletal rehabilitation, physical therapy and the basics of arthritis. Another addition was a collection of slides to use as learning sets for two specialized areas: pediatric rheumatology and the management of glucocorticoid-related osteoporosis.

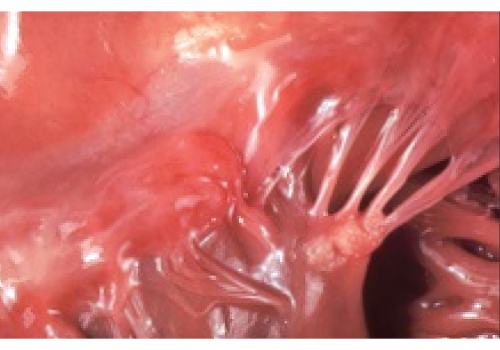

This beautifully composed photograph, without distracting features, shows Libman-Sacks endocarditis as seen at autopsy. In the days before echocardiography, clinicians knew of this lesion only by murmur, embolus or (rare) surgery for valve failure.

Dr. Matteson emphasizes just how educational and fun committee service was. “It was pure pleasure,” he says, describing interacting with the other committee members, learning about diseases, assessing the quality of slides and how they fit into the teaching program, and “of course, choosing the best and worst (spoof) slides made it all fun.”

Alan N. Baer, MD, professor of medicine and founder of the Jerome Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Clinic at Johns Hopkins University School of Medical, Baltimore, ushered the image collection into its current form—the ACR Image Library. Serving as committee chair from 2008–10, he worked with the committee to convert the entire collection of more than 1,000 slides to an online image bank, making the collection available to ACR members as a membership benefit.

Alan N. Baer, MD, professor of medicine and founder of the Jerome Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Clinic at Johns Hopkins University School of Medical, Baltimore, ushered the image collection into its current form—the ACR Image Library. Serving as committee chair from 2008–10, he worked with the committee to convert the entire collection of more than 1,000 slides to an online image bank, making the collection available to ACR members as a membership benefit.

Updating the Image Library to an online format has allowed for the inclusion of other technological updates, such as videos. “With the online format, we were able to expand our inclusion criteria for submissions,” says Dr. Baer. “Thus, we could now take videos and case series—multiple images devoted to one case.”

‘The Image Library is a great teaching tool for trainees & a repository of images for conditions/complications that may become increasingly rare as better treatments become available for our diseases.’ —Dr. Baer

One advancement that Dr. Baer was not able to get implemented was the idea of making each image submission a scholarly product that could be listed by the submitter on their curriculum vitae to count toward professional advancement (e.g., promotion, fellowships). “This idea has never been adopted,” he says. “The submissions remain anonymous to the users of the image bank.”

This gross specimen demonstrates a relatively normal coronary artery on the left and “beading” of the coronary artery on the right, secondary to segmental necrotizing arteritis.

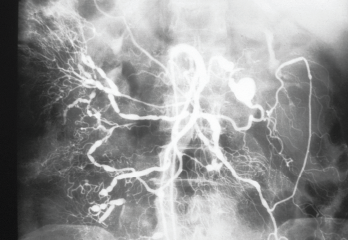

A selective angiogram of the superior mesenteric artery shows multiple saccular aneurysms that vary in size and shape. Note the irregularity of the vascular lumens with areas of stenosis and dilation.

The most recent committee chair, Chris Collins, MD, medical director for Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Rockville, Md., and formerly an associate professor of medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C., continues the long tradition of expanding the Image Library to keep up with the ever-changing technology.

The most recent committee chair, Chris Collins, MD, medical director for Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Rockville, Md., and formerly an associate professor of medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C., continues the long tradition of expanding the Image Library to keep up with the ever-changing technology.

All images, from the 191 original slides to the thousands currently in the collection to the new ones added each year, will “remain in perpetuity to provide an educational reservoir of what we see in clinical practice,” says Dr. Collins.

‘I don’t think people realize how storied an effort the Image Library has been.’ —Dr. Collins

Looking at the long history of the Image Library, he notes the brilliant minds in pathology and rheumatology who shaped the idea of creating a repository of images to teach fellow clinicians and the democratization of this effort to include the entire rheumatology community.

Bilateral scalp necrosis, an unusual finding in giant cell arteritis, is seen in this patient. Scalp necrosis is an uncommon manifestation of giant cell arteritis because of collateral arterial supply to the scalp.

In Sum

As history itself is a great teacher, one lesson that comes to mind when looking at the trajectory of how the ACR Image Library developed and evolved over time is how essential collaboration is to birthing an idea and carrying it forward to maturation.

A striking commonality among all the people who shared experiences of working on the Image Library committee is the strong memory of long hours working together and, notably, with the Bergmans—artists outside the clinical halls of medicine. Much has been written about the benefits of cross fertilization in learning, and perhaps the success of the Image Library over these many years is a testimony not only to the excellent educational tool it is, but also to the educational force that went into the process of creating the bank—visual artists and medical scientists, each bringing their respective craft to a collaborative project that continues to flourish and grow.

The Image Library has helped educate generations of rheumatologists and remains a critical teaching tool. “In the era of biological definitions of illness and, most recently, of telemedicine, careful physical examination remains an essential part of rheumatology (and of all medicine),” says Dr. Lockshin. “These images continue to have great teaching value; they make it possible for physicians to recognize something they may have heard of but have not previously seen and to validate their impressions by comparison with standard models.”

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in Minneapolis.

Corrected Oct. 28, 2020: Dr. Sidney Block has not retired. His private practice encompasses northern and eastern Maine.