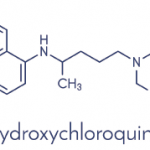

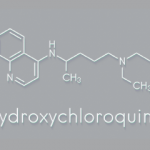

1991 Study

John M. Esdaile, MD, MPH, is the scientific director of Arthritis Research Canada and a professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He was a lead coordinator of the Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group, the joint authors of the 1991 paper.1

Dr. Esdaile recounts the debate in the medical community at the time: “Some people believed hydroxychloroquine didn’t work at all. Other people thought it was really useful, but there was a lack of evidence that you could use it safely. Either way, people didn’t want to study it.”

Dr. Petri

Dr. Petri adds, “Hydroxychloroquine wasn’t used universally, and if the skin or joint lupus activity were better, it might be tapered and stopped.”

Dr. Esdaile explains the FDA had grandfathered in approval for antimalarial class drugs. Thus, in comparison to drugs approved under current standards, drugs in this group had less rigorous evidence supporting them. Prior to the 1991 study, no prospective randomized studies of hydroxychloroquine had been performed, although data suggested it was beneficial for lupus patients. These earlier studies had shown that hydroxychloroquine might permit lower doses of corticosteroids to be used. They had highlighted the potential role of hydroxychloroquine and other antimalarials in decreasing skin, joint and constitutional symptoms, but had not examined the more severe manifestations of lupus.1

Based on his clinical experience treating lupus patients, Dr. Esdaile believed hydroxychloroquine was an underutilized and valuable drug. “One of the reasons I wanted to do the study,” he says, “was that I believed it worked. It was my gut sense that people on this drug did better. But it wasn’t scientific at all.”

Dr. Esdaile relates that he was influenced by an important study using antimalarials in lupus performed in 1975 by Naomi Rothfield, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.7 In this study, Dr. Rothfield et al. retrospectively studied patients with lupus who had been treated with antimalarials for at least two years and had then needed to stop them due to retinopathy. (The majority had been taking chloroquine at high doses.)

“[Dr. Rothfield] compared the period of time before patients had to stop due to eye toxicity to an equivalent period after they’d stopped it,” Dr. Esdaile explains. “She showed that there were flare-ups in the disease in the period after they’d stopped it. That intrigued me—this idea that it could stop these flare-ups in the disease activity.” Constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, and skin symptoms were more common after patients stopped the drug.7