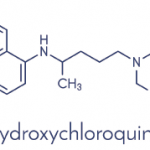

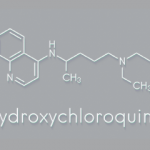

Given how unexpectedly front and center hydroxychloroquine has been in discussions about the treatment of COVID-19 this year, it makes sense to look at how it became so central to the treatment of a rheumatologic condition.

In 1991, an article appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine that would alter the way rheumatologists approached treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus: “A Randomized Study of the Effects of Withdrawing Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.”1 Although questions remained about optimal dosing, the study opened the way for much follow-up research that would confirm the drug’s critical importance for lupus patients.

Antimalarials: Background

Scientists synthesized the first antimalarial drugs shortly before the start of World War II. Malaria was a leading cause of death among soldiers, particularly in the South Pacific. The first antimalarial, quinacrine, produced numerous side effects, prompting researchers to develop derivate compounds. The U.S. Army introduced chloroquine, one of these compounds, in 1943.2

In 1951, Francis Page, MD, reported that quinacrine had beneficial effects on lupus symptoms.3 A similar report appeared two years later, when James Charles Shee, MD, published findings demonstrating that soldiers with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or lupus taking chloroquine showed clinical improvement.4

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center and a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, elaborates on the discovery of the drug’s use in inflammatory conditions. “The military personnel who had rheumatoid arthritis and lupus felt much better when they were taking the malaria medicine and then wanted to continue it when they left the military,” she explains. “It’s almost a discovery made accidentally, as so many medical discoveries are. It’s a nice story of physicians listening to their patients.”

Modifications to chloroquine eventually led to the introduction of an antimalarial purported to have fewer side effects, hydroxychloroquine, which the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved in 1955.2 The most commonly reported adverse effects of antimalarials are mild, such as gastrointestinal discomfort or headache. However, other concerns about the safety of antimalarials emerged over time, partly because doses for rheumatological conditions were much higher than those used for malaria prophylaxis.

A population-based, case-controlled study from 2019 demonstrated that the mortality risk increased almost fourfold in people who had to stop taking their hydroxychloroquine. It is the only drug that has been demonstrated to improve the survival of lupus patients.

In the late 1950s, reports began to appear documenting retinopathy resulting from chloroquine treatment.5 This important potential adverse effect continues to influence prescribing practices to this day.

Both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine can potentially bind in the retinal pigment epithelium and cause degeneration of photoreceptors, leading to retinopathy.6 Eventually, research demonstrated that hydroxychloroquine posed less of a risk of retinopathy than chloroquine.

In the U.S. and Canada, hydroxychloroquine has largely replaced chloroquine as a treatment for lupus in the antimalarial drug class.

1991 Study

John M. Esdaile, MD, MPH, is the scientific director of Arthritis Research Canada and a professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He was a lead coordinator of the Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group, the joint authors of the 1991 paper.1

Dr. Esdaile recounts the debate in the medical community at the time: “Some people believed hydroxychloroquine didn’t work at all. Other people thought it was really useful, but there was a lack of evidence that you could use it safely. Either way, people didn’t want to study it.”

Dr. Petri

Dr. Petri adds, “Hydroxychloroquine wasn’t used universally, and if the skin or joint lupus activity were better, it might be tapered and stopped.”

Dr. Esdaile explains the FDA had grandfathered in approval for antimalarial class drugs. Thus, in comparison to drugs approved under current standards, drugs in this group had less rigorous evidence supporting them. Prior to the 1991 study, no prospective randomized studies of hydroxychloroquine had been performed, although data suggested it was beneficial for lupus patients. These earlier studies had shown that hydroxychloroquine might permit lower doses of corticosteroids to be used. They had highlighted the potential role of hydroxychloroquine and other antimalarials in decreasing skin, joint and constitutional symptoms, but had not examined the more severe manifestations of lupus.1

Based on his clinical experience treating lupus patients, Dr. Esdaile believed hydroxychloroquine was an underutilized and valuable drug. “One of the reasons I wanted to do the study,” he says, “was that I believed it worked. It was my gut sense that people on this drug did better. But it wasn’t scientific at all.”

Dr. Esdaile relates that he was influenced by an important study using antimalarials in lupus performed in 1975 by Naomi Rothfield, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.7 In this study, Dr. Rothfield et al. retrospectively studied patients with lupus who had been treated with antimalarials for at least two years and had then needed to stop them due to retinopathy. (The majority had been taking chloroquine at high doses.)

“[Dr. Rothfield] compared the period of time before patients had to stop due to eye toxicity to an equivalent period after they’d stopped it,” Dr. Esdaile explains. “She showed that there were flare-ups in the disease in the period after they’d stopped it. That intrigued me—this idea that it could stop these flare-ups in the disease activity.” Constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, and skin symptoms were more common after patients stopped the drug.7

Dr. Esdaile

Dr. Esdaile, who trained nearby at Yale University, spoke to Dr. Rothfield in detail about the work. He coordinated the study out of Montreal General Hospital, Quebec, Canada, where he was working at the time. He recruited doctors from two other hospitals in Montreal, from a hospital in Ottawa and from another in Hamilton, Ontario. Those physicians then asked their colleagues to send them any lupus patients who were doing well and currently taking hydroxychloroquine.

“The fact that the Canadians banded together to do this is a remarkable substory of this paper,” says Dr. Petri. “They are lumped together as the Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. This is a great example of clinicians caring about lupus and not caring about their own names or their own egos.”

Study Design & Outcomes

Dr. Esdaile and colleagues opted to perform a prospective, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study to examine the potential protective role of hydroxychloroquine in preventing disease flares.

The group studied lupus patients who had been taking hydroxychloroquine in doses ranging from 100 mg to 400 mg per day. The average length of time the lupus patients had been taking hydroxychloroquine was three years, and all patients had taken it for at least six months. All had experienced clinical remission or only minimal disease activity for the three months prior to study initiation. The patients were randomized to either continue taking hydroxychloroquine at their current dose or to take a placebo.1

Dr. Esdaile explains the characteristics of lupus make it challenging to study. He partly chose the withdrawal design because lupus often requires intensive intervention with stronger drugs, such as prednisone for flares of disease activity. He believed the effect of that would obscure the impact of hydroxychloroquine, making benefits harder to see.

In 2016, the American Academy of Ophthalmology published guidelines for hydroxychloroquine patient monitoring, recommending optical coherence tomogram at baseline, five years thereafter & then every year following for patients without major risk factors for retinopathy. … In terms of toxicity, recent guidelines … recommend lowering the dosage from 6.5 mg/kg patient weight to less than 5.0 mg/kg.

“If you used people who had never seen hydroxychloroquine, the flare would create a nightmare for analysis,” he says. “Whereas the way we designed it, the flareup was the outcome.” Additionally, because many doctors and patients had concerns about taking the drug continuously, Dr. Esdaile says it would have been more difficult to find patients to enroll in a trial of patients naive to hydroxychloroquine.

Blinding the study properly was a challenge, because hydroxychloroquine formulations at the time had a strong, unpleasant taste. Dr. Esdaile worked with the drug manufacturer to obtain a drug and a placebo in identical shapes. To help with the disguise, the placebos were coated with a trace amount of hydroxychloroquine (<1 mg), so they would also have an unpleasant taste.

The group assessed patients every four weeks over a 24-week period using standard clinical assessments and laboratory tests. Final analyses included 47 patients with lupus.1 Using data from Dr. Rothfield’s work, Dr. Esdaile and colleagues estimated that staying on hydroxychloroquine would reduce flares by about 50% with their study design.

Dr. Esdaile and colleagues found the relative risk of a clinical flare-up (the primary outcome) was 2.5 times higher in patients taking placebo than in those who had continued to take hydroxychloroquine. Moreover, the relative risk of the secondary outcome, severe disease exacerbation, was six times higher in patients taking placebo than in those who had continued taking hydroxychloroquine. (This, however, did not reach statistical significance, which was unsurprising given study size and length.)

The findings also provided early evidence that hydroxychloroquine treatment might reduce nephritic flares successfully. Efforts to properly blind the study were successful, with only 53% of participants correctly guessing whether they were taking hydroxychloroquine or placebo.1

“It was a remarkably simple study, and the preventive role of hydroxychloroquine was so strong,” Dr Petri remarks. She contrasts the sample size with those found in modern studies using much higher numbers of patients. She adds, “I often say if something really works, you don’t need a lot of patients to show it. And that’s one reason why I think this is such a wonderful study.”

The randomized withdrawal trial design is now only rarely used in lupus, although it is still sometimes employed in juvenile chronic arthritis studies. Dr. Petri says, “I think this shows that maybe we’ve forgotten it’s a good study design.”

Randomized withdrawal trials do present problems of generalizability. For example, such a trial design excludes patients who had previously discontinued hydroxychloroquine due to lack of response, toxicity or other factors, and thus may tend to overestimate efficacy.

But Dr. Esdaile emphasizes that one of the design’s strengths is the ability to show an effect with a smaller sample size.

Study Impact

The paper attracted much interest and served as the focus of a plenary session at that year’s ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting. Due to its influence, physicians became much more likely to prescribe hydroxychloroquine over the long term. Sales of the drug, still under patent then, went up markedly after the paper’s release.

Today, hydroxychloroquine is a staple treatment of lupus. In the absence of rare contraindications, most experts recommend lifelong treatment with hydroxychloroquine for all lupus patients, regardless of disease severity or additional therapies.

“The study demonstrated that hydroxychloroquine wasn’t just for active lupus, but had a major preventive role,” Dr. Petri says.

In addition to lupus, hydroxychloroquine is less frequently used to treat RA and certain other inflammatory rheumatologic diseases. The drug is also under consideration for new applications, such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus and certain cancers.8

Since the initial study by the Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group, researchers in other follow-up studies have confirmed the important role of hydroxychloroquine in preventing lupus disease flares. Scientists have also learned much about the drug’s multiple beneficial effects. Over the years, it has become evident that hydroxychloroquine does more than suppress mild disease, as was initially believed.

Explains Dr. Petri, “I’ve spent the past 34 years trying to build on what the Canadians showed back in 1991. We know now [hydroxychloroquine] helps improve survival; it reduces cardiovascular risk factors, thrombosis, renal damage, central nervous system lupus and more.”

A population-based, case-controlled study from 2019 demonstrated that mortality risk increased almost fourfold in people who had to stop taking their hydroxychloroquine.9 It is the only drug that has been demonstrated to improve the survival of lupus patients. Hydroxychloroquine also appears to be a safe and effective drug in pregnant patients, reducing flares during this time and decreasing the risk of cardiac neonatal lupus.6

Continued Safety Concerns for Hydroxychloroquine

Although the potential impact of hydroxychloroquine is undeniable, its safety is again being questioned. For reasons that are unclear, the incidence of retinopathy appears to have been increasing in recent years. Dr. Petri notes that research has demonstrated that retinopathy from hydroxychloroquine is more common than previously thought. This is a major concern, because late retinopathy is not reversible, and no currently available therapies can treat it.8

Dr. Petri et al. recently published an article demonstrating that about 11% of lupus patients taking hydroxychloroquine will have to stop it after 16 years due to signs of early retinopathy.10 Dr. Petri explains this may be due to the greater sensitivity of newer ophthalmology screening tests for retinopathy, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), which may be picking up milder retinopathy at a much earlier stage than was possible in the past.

“We are facing the fact that hydroxychloroquine is not going to be allowed in every single patient for their lifetime of lupus,” she says. “I’m always annoyed when I get a note from an ophthalmologist who tells me to start a substitute for hydroxychloroquine due to retinopathy. We do not have a substitute for it; we have nothing to replace it.”

She hopes this will serve as an impetus for the research community to find better or additional lupus therapies.

In 2016, the American Academy of Ophthalmology published guidelines for hydroxychloroquine patient monitoring, recommending OCT at baseline, five years thereafter and then every year following for patients without major risk factors for retinopathy.8

Questions also remain about optimal dosing of the drug. Higher doses have been associated with a greater risk of retinopathy. In terms of toxicity, recent guidelines from the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommend lowering the dosage from 6.5 mg/kg patient weight to less than 5.0 mg/kg.8

Dr. Petri responds, “The concern has been, if you reduce the dose, we’re going to reduce the efficacy.” At the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting, Dr. Petri presented data demonstrating that lowered blood levels of hydroxychloroquine did, in fact, increase the risk of thrombosis in lupus patients.11

Hydroxychloroquine blood levels may provide a way to find optimal efficacy with a lower risk of retinopathy. Dr. Petri explains, “Blood levels reflect how much the patient has taken over the past month, very similar to a hemoglobin A1c in diabetes; it’s really reflective of their adherence.” She believes these blood levels can help identify people who are taking more hydroxychloroquine than needed—people who could safely have their dose lowered.

Hydroxychloroquine blood levels are becoming more universally available. Dr. Petri explains that Exagen provides a commercial source, and labs like Quest Diagnostics also offer them. “Some other labs,” she notes, “have offered plasma levels, which aren’t as accurate. Hydroxychloroquine binds to red cells, so plasma grossly underestimates the actual exposure. This is a field in flux—using therapeutic blood monitoring to guide dosing of hydroxychloroquine, so that we do not give too little or too much.”

Next Steps

Knowing how to optimize safe dosing for hydroxychloroquine at a population level is the goal of a new study. Dr. Esdaile is collaborating with Antonio Aviña-Zubieta, MD, PhD, on a prospective study involving all patients receiving hydroxychloroquine for lupus and RA in the province of British Columbia.

Dr. Petri and other rheumatology and ophthalmology experts in the field will be working to develop specific recommendations for clinicians, but these are not expected soon. Until then, rheumatologists can follow recommended eye monitoring schedules. This should pick up any potential retinopathy early, before symptoms begin and without risk of further progression if hydroxychloroquine is stopped. In so doing, rheumatologists hope to keep using one of their key tools in the treatment of lupus.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. A randomized study of the effect of withdrawing hydroxychloroquine sulfate in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1991 Jan 17;324(3):150–154.

- Shippey EA, Wagler VD, Collamer AN. Hydroxychloroquine: An old drug with new relevance. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018 Jun;85(6):459–467.

- Shee JC. Lupus erythematosus treated with chloroquine. Lancet. 1953 Jul 25;265(6778):201–202.

- Page F. Treatment of lupus erythematosus with mepracine. Lancet. 1951 Oct 27;2(6687):755–758.

- Mackenzie AH. An appraisal of chloroquine. Arthritis Rheum. 1970 May–Jun;13(3):280–291.

- Lee SJ, Silverman E, Bargman JM. The role of antimalarial agents in the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011 Oct 18;7(12):718–729.

- Rudnicki RD, Gresham GE, Rothfield NF. The efficacy of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1975 Sep;2(3):323–330.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TYY, et al. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology. 2016 Jun;123(6):1386–1394.

- Avina-Zubieta A, Jorge A, DeVera MA, et al. Increased mortality among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus after hydroxychloroquine discontinuation (abstract 299). Lupus Sci Med. 2019;6(Supp 1):A217–A218.

- Petri M, Elkhalifa M, Li J, et al. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels predict hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Mar;72(3):448–453.

- Konig M, Li J, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels and risk of thrombotic events in systemic lupus erythematosus [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10).