With the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s approval in 2014 of asfotase alfa for replacement of tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP or TNAP) in juvenile-onset hypophosphatasia (HPP), rheumatologists have a responsibility to recognize the more subtle manifestations of this condition in adults to avoid missed treatment opportunities for fractures, dental loss and musculoskeletal pain.

With the U.S. Food & Drug Administration’s approval in 2014 of asfotase alfa for replacement of tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP or TNAP) in juvenile-onset hypophosphatasia (HPP), rheumatologists have a responsibility to recognize the more subtle manifestations of this condition in adults to avoid missed treatment opportunities for fractures, dental loss and musculoskeletal pain.

Hypophosphatasia is a heterogenous disorder deriving from more than 400 known mutations in the alkaline phosphatase gene (ALPL), presenting in both children and adults with persistently low alkaline phosphatase levels and associated abnormalities that vary widely—from osteomalacia and fractures to chondrocalcinosis and (sometimes exclusively) abnormalities of dental mineralization or premature tooth loss. The shared deficits in affected individuals relate to an impact of loss-of-function mutations in the tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase enzyme responsible for manufacturing inorganic phosphate from pyrophosphate for incorporation into bone matrix, with additional impact on vitamin B6 metabolism resulting in difficulty transporting B6 from the blood into the central nervous system.1

Prevalence & Diagnosis

Hypophosphatasia is a rare condition: Estimates of the prevalence of severe disease in children range from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 300,000, and the prevalence of milder disease is presumed to be higher in adults but is not yet informed by reliable population-based data.2

The condition must be distinguished from more common causes of persistently low alkaline phosphatase, including nutritional deficiencies, celiac disease, hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism, bisphosphonate use, chemotherapy and adynamic renal osteodystrophy.3

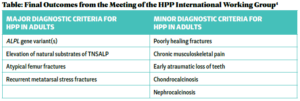

Recent proposed diagnostic criteria by the HPP International Working Group for patients with persistent hypophosphatemia include four major and nine minor criteria—of which two major, or one major and two minor criteria must be present (see Table).4 These criteria have not yet been validated but represent the first consensus guidelines for diagnosis in both pediatric and adult populations.

Musculoskeletal Signs & Symptoms

Importantly for rheumatologists, musculoskeletal signs and symptoms are common among adults with hypophosphatasia. In one review, the pooled prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms was high, including 64% of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, 64% with poorly healing fractures, 39% with recurrent metatarsal stress fractures and 16% with chondrocalcinosis or calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease. Overall, the prevalence of dental abnormalities included early loss of primary teeth in 34% and loss of secondary teeth without periodontal disease in 5%.4

Ligamentous calcium hydroxyapatite deposition is another consequence of the disordered inorganic phosphate handling, resulting in calcific enthesopathy and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis.5