The Comarmond study was large enough to assess strong risk factors for increased mortality, which were limited to cardiomyopathy and age.2

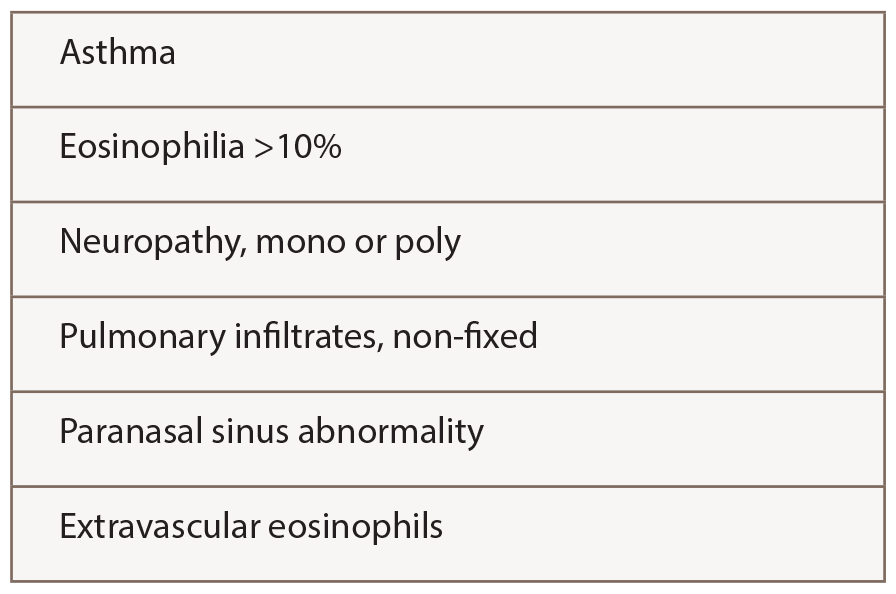

The ACR criteria (see Table 2) used by Comarmond and Durel were developed for classification rather than diagnosis, meaning the patient is presumed to have a confident diagnosis of vasculitis of some sort. In practice, the ACR criteria probably perform well for EGPA, because four features are required, rather than just two or three as for other vasculitides.

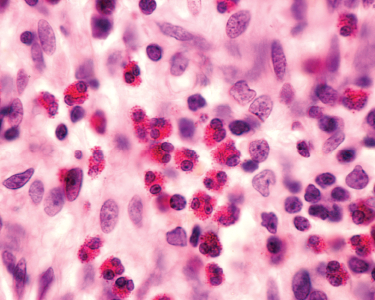

The remaining concern is that hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) not featuring vasculitis could be classified as EGPA. Several groups have added ANCA as a criterion distinguishing EGPA from HES, but that captures only 30–40% of patients currently regarded as having EGPA. Parenthetically, in ANCA-negative patients without biopsy proof of vasculitis, it is particularly important to address a broader differential diagnosis using tests proposed by Groh and others.5

(click for larger image)

Table 2: ACR 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Churg-Strauss Syndrome

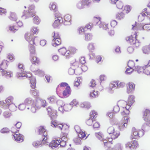

With this background, Cottin et al. studied 157 patients meeting the Lanham criteria for Churg-Strauss syndrome, although 94% also met ACR criteria.4 They compared the features of ANCA-positive (31%) and ANCA-negative (69%) patients and concluded that a patient could be defined as having polyangiitis by having either ANCA, biopsy proof of vasculitis (in any tissue) or evidence of GN, alveolar hemorrhage or mononeuritis multiplex.

Sixty-four patients in this cohort (41%) did not have evidence of polyangiitis, and Cottin et al. propose the term hypereosinophilic asthma with systemic manifestations (HASM) to describe them. Rates of relapse and use of immune-suppressive drugs did not differ. Whether the term HASM will be accepted is unknown.

A similar exercise among patients meeting criteria for HES, subdivided by the presence or absence of mutations, such as FIP1L1-PDGFRA, would be informative to see whether mutation-negative HES may be the same as HASM, although more mutations undoubtedly await discovery.

What is missing from the paper by Cottin et al.—and would be most helpful in evaluating the concept of HASM—is an analysis of patients who met criteria for EGPA/CSS and HASM (but not polyangiitis) at diagnosis but developed evidence of polyangiitis later, compared with a cohort with polyangiitis at diagnosis.

Treatment—Including Randomized Trials

Do these distinctions, or other features of disease, have implications for treatment? Treatments chosen in these observational studies always included prednisone, often with addition of either cyclophosphamide (for organ-threatening disease) or methotrexate or azathioprine (for less severe disease). The literature on effectiveness of these drugs is scant.5 Cyclophosphamide became standard of care for severe disease based on the better outcomes seen with such treatment in an observational cohort of patients with elevated creatinine, significant proteinuria, cardiac involvement, severe GI involvement or CNS involvement—the Five Factor Score (FFS) developed by the FVSG by studying EGPA and other systemic vasculitides simultaneously.5-7 Since involvement of these organ systems could be due to vasculitis (renal), eosinophilic inflammation (cardiac) or GI, it’s quite possible that treatments could differ, but it seems wise not to risk undertreatment of such patients.