Rawpixel.com / shutterstock.com

The past five years have been busier than usual for the Churg-Strauss syndrome. It was renamed eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).1 Longitudinal cohorts totaling 484 patients—approximately as many as all previous series combined—were described.2,3 A proposal was advanced to remove and rename a subset in which vasculitis may not be present.4 And shortly after the production of consensus guidelines for management, the portion of the evidence base comprising relatively large, randomized trials more than doubled.5

The Long & the Short of It

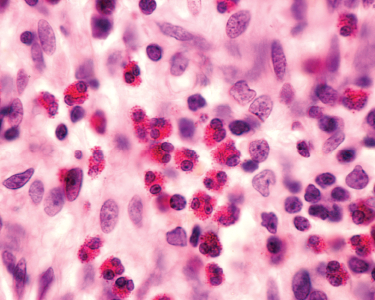

EGPA is a good name—and manageable once shortened to four letters. It describes the definitive pathology well. Just as with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, Wegener’s), EGPA does not feature granulomatous vasculitis, nor are eosinophils essential to the process of vasculitis. Rather, the eosinophilic granulomas are nearby, hence “with.” GPA is no longer the only rheumatic disease with a “with” in the name.

Churg-Strauss is an easier name to remember, but it doesn’t help physicians remember the clinical features, nor does it help patients educate their family and friends. What isn’t captured in the new name is that many features of the disease are characterized by eosinophilic inflammation into tissues, without necessarily being accompanied by vasculitis or necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. As far as can be determined, the pathology of nasal inflammation is indistinguishable from that of isolated nasal polyps; the parenchymal lung pathology is often the same as isolated eosinophilic pneumonia; and the eosinophilic myocarditis is indistinguishable from that seen in hypereosinophilic syndromes.

Sometimes 100 Is a Lot

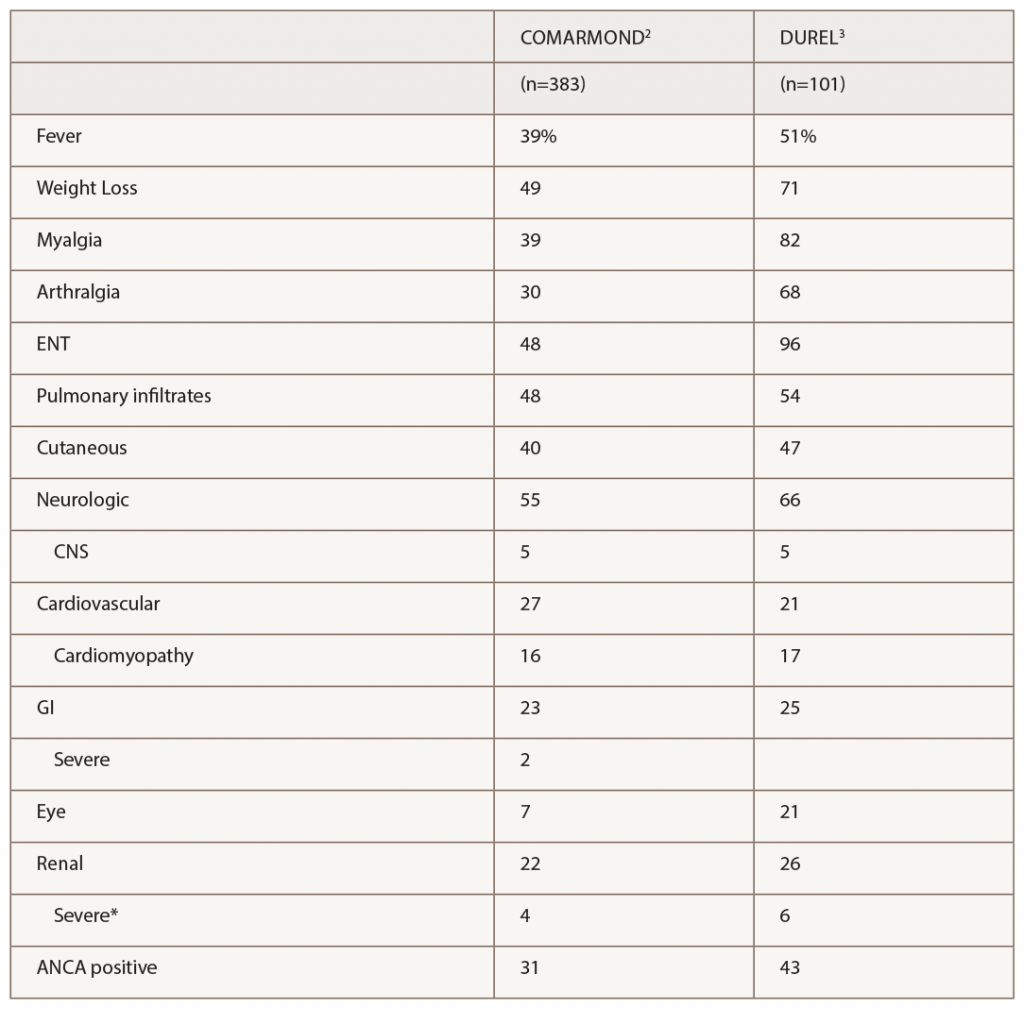

(click for larger image) Table 1: Manifestations of EGPA in 2 Recent Observational Cohort Studies

* Severe renal disease was defined by Comarmond as meeting Five Factor Score criteria for reduced renal function or proteinuria, and by Durel as having evidence for glomerulonephritis.

The series by Comarmond and the French Vasculitis Study Group (FVSG), and by Durel, provide useful details on clinical manifestations. A summary of organ system involvement is shown in Table 1, but readers are advised to look in the papers at the diversity of manifestations within a given organ system. For example, in the FVSG study, cutaneous manifestations (present in 40% of patients at diagnosis) are subdivided into purpura (23%), urticarial lesions (10%), subcutaneous nodules (10%), livedo reticularis (4%) and necrotic/gangrenous lesions (4%). Kidney involvement was surprisingly high (22–26%), but severe involvement was much less common (4–6%).2,3 Consistent with previous studies, 31–43% of patients were ANCA positive, and this was the group at risk for GN.3 Also consistent with previous studies, ANCA-positive patients were more likely to have peripheral neuropathy and ANCA-negative patients were more likely to have cardiomyopathy, although differences were not nearly as large as with GN.

The Comarmond study was large enough to assess strong risk factors for increased mortality, which were limited to cardiomyopathy and age.2

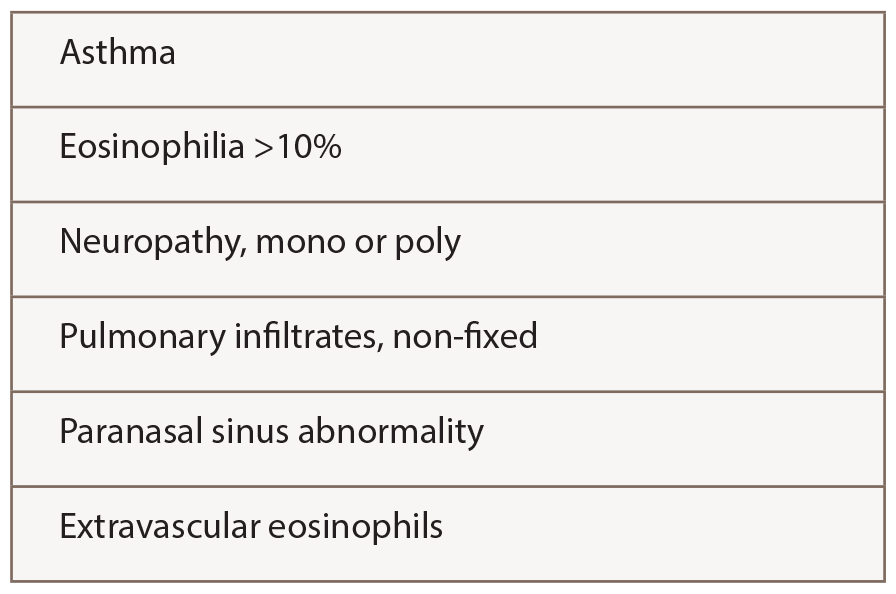

The ACR criteria (see Table 2) used by Comarmond and Durel were developed for classification rather than diagnosis, meaning the patient is presumed to have a confident diagnosis of vasculitis of some sort. In practice, the ACR criteria probably perform well for EGPA, because four features are required, rather than just two or three as for other vasculitides.

The remaining concern is that hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) not featuring vasculitis could be classified as EGPA. Several groups have added ANCA as a criterion distinguishing EGPA from HES, but that captures only 30–40% of patients currently regarded as having EGPA. Parenthetically, in ANCA-negative patients without biopsy proof of vasculitis, it is particularly important to address a broader differential diagnosis using tests proposed by Groh and others.5

(click for larger image)

Table 2: ACR 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Churg-Strauss Syndrome

With this background, Cottin et al. studied 157 patients meeting the Lanham criteria for Churg-Strauss syndrome, although 94% also met ACR criteria.4 They compared the features of ANCA-positive (31%) and ANCA-negative (69%) patients and concluded that a patient could be defined as having polyangiitis by having either ANCA, biopsy proof of vasculitis (in any tissue) or evidence of GN, alveolar hemorrhage or mononeuritis multiplex.

Sixty-four patients in this cohort (41%) did not have evidence of polyangiitis, and Cottin et al. propose the term hypereosinophilic asthma with systemic manifestations (HASM) to describe them. Rates of relapse and use of immune-suppressive drugs did not differ. Whether the term HASM will be accepted is unknown.

A similar exercise among patients meeting criteria for HES, subdivided by the presence or absence of mutations, such as FIP1L1-PDGFRA, would be informative to see whether mutation-negative HES may be the same as HASM, although more mutations undoubtedly await discovery.

What is missing from the paper by Cottin et al.—and would be most helpful in evaluating the concept of HASM—is an analysis of patients who met criteria for EGPA/CSS and HASM (but not polyangiitis) at diagnosis but developed evidence of polyangiitis later, compared with a cohort with polyangiitis at diagnosis.

Treatment—Including Randomized Trials

Do these distinctions, or other features of disease, have implications for treatment? Treatments chosen in these observational studies always included prednisone, often with addition of either cyclophosphamide (for organ-threatening disease) or methotrexate or azathioprine (for less severe disease). The literature on effectiveness of these drugs is scant.5 Cyclophosphamide became standard of care for severe disease based on the better outcomes seen with such treatment in an observational cohort of patients with elevated creatinine, significant proteinuria, cardiac involvement, severe GI involvement or CNS involvement—the Five Factor Score (FFS) developed by the FVSG by studying EGPA and other systemic vasculitides simultaneously.5-7 Since involvement of these organ systems could be due to vasculitis (renal), eosinophilic inflammation (cardiac) or GI, it’s quite possible that treatments could differ, but it seems wise not to risk undertreatment of such patients.

Medications traditionally used for milder disease or for steroid-sparing long term, such as azathioprine and methotrexate, work in diverse inflammatory diseases, but newer approaches may not.8

An early randomized trial in EGPA, limited to patients with non-severe disease (FFS=0) who relapsed after initial induction of remission with glucocorticoids alone, suggested that azathioprine could restore and maintain remission in most cases, meaning seven of nine patients.9 Because it is difficult to conduct large trials in EGPA, other studies from the FVSG have often grouped patients with different vasculitides together based on their perceived similarity in response to immune-suppressive treatment, a controversial practice but likely essential for completing a study with sufficient statistical power to detect moderate differences.

In a recent randomized, double-blind trial from Puechal and the FVSG, EGPA (51 patients) was grouped with nonsevere microscopic polyangiitis (MPA; 25 patients) or polyarteritis nodosa (19 patients), to compare azathioprine 2 mg/kg with placebo in addition to a standard prednisone regimen.10 A combined outcome of failure to induce remission (less than 10% overall and only 2% of the EGPA subgroup) and relapse (about 40% overall, and 45% in EGPA) was used. Importantly, a relapse had to include manifestations beyond flare of asthma or rhinosinusitis. In contrast to the first study, no evidence exists that azathioprine reduced the rate of relapse. A major limitation of this study was that many relapses occurred after discontinuation of either azathioprine (12 of 19 across all three diseases) or placebo (eight of 17). Also, the EGPA group consisted of only 51 patients. Despite these limitations, it is notable the relapse rate wasn’t just “not significantly different,” but was strikingly similar. Thus, although this study does not really show that azathioprine doesn’t work in EGPA, it strongly suggests that it doesn’t work very well.

An approach aimed at the biology of eosinophils gave more promising results. Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin 5, an important developmental factor for eosinophils. It is FDA approved for asthma with eosinophilia at 100 mg monthly by subcutaneous injection. It has previously shown promise, at 300 mg monthly, in treating EGPA and HES in very small studies.

With that background, an industry-sponsored, double-blind, randomized trial was conducted by Wechsler et al. in 136 patients at multiple centers in Europe and the U.S.11 All patients had to have met criteria for EGPA at some point, of course, but the enrollment criteria were permissive and can be summarized as “inability to get prednisone dose below 7.5 mg without relapsing,” regardless of the reason. Patients were allowed to remain in the study if they had minor flares that required increases in prednisone. Remission was defined as absence of symptoms on no more than 4 mg prednisone and was analyzed in different ways.

In the group receiving 300 mg mepolizumab monthly, 28% were in remission for at least 24 weeks in the 48-week study, compared with only 3% in the placebo group; similarly, 32% of patients in the mepolizumab group were in remission at both Weeks 36 and 48 (prespecified), compared with 3% in the placebo group. However, to dampen enthusiasm somewhat, 47% of patients receiving mepolizumab never met criteria for remission (compared with 81% in the placebo group), and the average prednisone dose dropped only from 12 mg to 5 mg (compared with being unchanged at 10–12 mg in the placebo group throughout the trial). It is also impossible to determine how many patients had flares of vasculitis (i.e., polyangiitis) or severe parenchymal eosinophilic disease above and beyond asthma or sinonasal disease, because vasculitis was defined as any items on the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS), which includes such factors as fatigue and arthralgia.

Because rituximab is as effective as cyclophosphamide for treating ANCA-positive patients with GPA and MPA, the question arises whether rituximab is also effective in treating EGPA, which also features small-vessel vasculitis and in which 30–40% of patients have ANCA, usually anti-myeloperoxidase. This question has not yet been addressed in a trial, but experience suggesting benefit has been described in a retrospective study of 41 patients assembled from several referral centers.12 Historical manifestations, prior disease courses and prior treatments were diverse, similar to large case series, and 44% of patients were ANCA positive. Whether glucocorticoids were increased in some patients around the time rituximab was initiated was not reported, but the median dose of prednisone/prednisolone dropped from 15 mg at baseline to 8 mg at six and 12 months after starting rituximab. Remission, defined as BVAS=0, was achieved in 12 of 15 (80%) ANCA-positive patients and eight of 21 (38%) ANCA-negative patients.

Although [Puechal] does not really show that azathioprine doesn’t work in EGPA, it strongly suggests that it doesn’t work very well.

What I Do … (Is 30 Ever a Lot?)

For assessing severity, I find the original FFS (including CNS, cardiac, significant renal or severe GI involvement) to be useful in defining severe disease, but I would add pulmonary hemorrhage (rare in EGPA) and have a low threshold for adding peripheral neuropathy in light of its likelihood of leading to chronic pain and disability.

For patients with severe disease, I use a regimen similar to GPA or MPA, except that for EGPA I would almost always use cyclophosphamide (oral or IV, for three to six months) rather than rituximab. In contrast to GPA and MPA, for ANCA-positive patients with EGPA I would count on rituximab only to control GN or pulmonary hemorrhage. The glucocorticoid regimen I typically use in patients with severe EGPA, as with GPA or MPA, is an IV pulse of methylprednisolone, followed by 60, 50, 40, 30, 20, 15, 10, 7.5, 5 and 2.5 mg for two weeks each. In practice, the prednisone tapering usually needs to be slowed and eventually halted based on recurrent inflammatory disease in the upper or lower airway. Then, the task is steroid sparing, just as in a patient whose initial presentation was nonsevere.

For patients with nonsevere EGPA, an initial dose of 40–60 mg prednisone is often needed, but I try to reduce more rapidly and quickly establish the minimum dose required to control symptoms, then taper slowly from there. Such regimens end up being highly variable. Prednisone alone is almost always effective for initial treatment, so addition of another immunosuppressive drug is made on the basis of, or in anticipation of the need for, steroid sparing. When to start such a drug is based on guesswork, factoring in the likely two to three months to see benefit. In the absence of data, by analogy to GPA and MPA, I consider methotrexate (20–25 mg/week) and azathioprine (2 mg/kg daily) to be equivalent, and mycophenolate (2,000–3,000 mg daily) to also be a reasonable option.

However, in light of the success of mepolizumab in a randomized trial, and the good safety profile seen so far in that study and in previous studies in asthma, I am inclined to try mepolizumab if the first oral immunosuppressive drug does not provide sufficient benefit. I don’t see any particular reason to use the 300 mg dose approved for EGPA rather than the 100 mg dose previously approved for asthma with eosinophilia, because the latter circumstance is often what keeps patients with EGPA on prednisone chronically. But it is reasonable to start with 300 mg (and consider reducing to 100 mg later) or start with 100 mg (and increase to 300 mg if needed).

Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jiroveci and attention to bone health are important, and the minimum dose of immune suppression at which it is safe to discontinue Pneumocystis prophylaxis has not been established.

Other approaches to control asthma should still be encouraged in collaboration with a pulmonologist and not abandoned once a patient is diagnosed with EGPA. These approaches include leukotriene inhibitors; after concern was raised that these drugs might cause EGPA in a small percentage of patients with asthma, the later consensus among experts has been that they can unmask it by allowing reduction in chronic glucocorticoid doses. Patients may require surgical removal of nasal polyps if these do not resolve with medications. Attempts to manage neuropathic pain are often required and often unsatisfactory.

I follow eosinophil counts, ESR, and CRP levels regularly, along with ANCA titers in patients previously ANCA positive, and CK and troponin in patients with a history of cardiac involvement. That being said, eosinophil counts, ESR, and CRP perform poorly as biomarkers of active disease (using clinical assessment as the gold standard) once a patient is on glucocorticoids, and this unfortunate finding has been made with promising experimental biomarkers as well.13,14 The value of serial ANCA measurements continues to be debated in GPA and MPA, and their value can’t be more helpful in EGPA than in MPA. I like to think that normal CK and troponin, in contrast, are fully reassuring about absence of ongoing cardiac damage, in the absence of any data.

In the end, at least as much as in other chronic rheumatic diseases, management of EGPA involves a long-term discussion with the patient to balance control of symptoms and medication side effects, based more on subjective experiences than on objective findings.

Paul A. Monach, MD, PhD, is chief of the rheumatology section of the VA Boston Healthcare System and an associate professor in the Section of Rheumatology of the Boston University School of Medicine. He specializes in clinical care and clinical research in vasculitis.

Disclosure: I was a site investigator in the recent trial of mepolizumab in EGPA.11

References

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

- Comarmond C, Pagnoux C, Khellaf M, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): Clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):270–281.

- Durel CA, Berthiller J, Caboni S, et al. Long-term followup of a multicenter cohort of 101 patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Mar;68(3):374–387.

- Cottin V, Bel E, Bottero P, et al. Revisiting the systemic vasculitis in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): A study of 157 patients by the Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies Orphelines Pulmonaires and the European Respiratory Society Taskforce on eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Autoimmun Rev. 2017 Jan;16(1):1–9.

- Groh M, Pagnoux C, Baldini C, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA) Consensus Task Force recommendations for evaluation and management. Eur J Intern Med. 2015 Sept;26(7):545–553.

- Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, et al. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996 Jan;75(1):17–28.

- Gayraud M, Guillevin L, le Toumelin P, et al. Long-term followup of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome: Analysis of four prospective trials including 278 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Mar;44(3):666–675.

- Samson M, Puéchal X, Devilliers H, et al. Long-term outcomes of 118 patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) enrolled in two prospective trials. J Autoimmun. 2013 Jun;43:60–69.

- Ribi C, Cohen P, Pagnoux C, et al. Treatment of Churg-Strauss syndrome without poor-prognosis factors: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label study of seventy-two patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Feb;58(2):586–594.

- Puéchal X, Pagnoux C, Baron G, et al. Adding azathioprine to remission-induction glucocorticoids for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss), microscopic polyangiitis, or polyarteritis nodosa without poor prognosis factors: A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:2175–2186.

- Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, et al. Mepolizumab or placebo for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. N Engl J Med. 2017 May;376(20):1921–1932.

- Mohammad AJ, Hot A, Arndt F, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Feb;75(2):396–401.

- Grayson PC, Monach PA, Pagnoux C, et al. Value of commonly measured laboratory tests as biomarkers of disease activity and predictors of relapse in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015 Aug;54(8):1351–1359.

- Dejaco C, Oppl B, Monach P, et al. Serum biomarkers in patients with relapsing eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). PLoS One. 2015 Mar 26;10(3):e0121737.