A 20-year-old Mexican woman presented to a local health facility in Corpus Christi, Texas, complaining of three days of difficulty in breathing and chest pain on inspiration. A month prior to the onset of these symptoms, she had delivered a healthy baby boy. Of note, she was in good health prior to the pregnancy, and her pregnancy and delivery had been uneventful. However, she had not received any routine prenatal care. Her physical examination at the presentation to the health facility was negative. She was given a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug to alleviate her chest discomfort and advised to return if her symptoms worsened. They did. Within two days, she was barely able to breathe and was coughing up blood-tinged sputum. She was taken to the local hospital, where she was found to have bilateral pulmonary infiltrates consistent with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; her white blood cell and platelet counts were decreased, and she was moderately anemic. Laboratory studies indicated the presence of proteinuria, hematuria, and cellular casts on her urine. She was admitted to the intensive care unit where, despite mechanical ventilation, fluids, antibiotics, and glucocorticoids, her condition continued to deteriorate. She died within 48 hours.

Sadly, despite all of the advances in medicine in this country, cases like this patient’s continue to be all too common and dramatize the gaps in our scientific understanding of lupus as well as the serious gaps in our healthcare system. Although this case occurred in Texas, this young woman reminds me of the patients I saw in the 1960s as a medical student in my native Perú—patients with rapidly evolving lupus who, oftentimes, did not survive.

The challenge of managing patients like these was my primary motivation for becoming a rheumatologist. For years, rheumatologists charged with the care of Hispanic patients in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California had observed patients with rapidly evolving lupus characterized by severe organ involvement, much in the same way as it had been observed in individuals of African descent for decades throughout the United States. With Hispanics now constituting the largest and fastest-growing U.S. minority population group, patients of this descent are presenting not only in the Southwestern states but all across the country. Today, rheumatologists, no matter the setting, need to be aware of the potentially very serious outcomes of Hispanic patients with lupus.

Genesis of LUMINA

In 1993, a unique opportunity to participate in lupus research arose for me when the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) issued a Request for Applications (RFA) to study lupus in minorities. I felt that the time was right to expand the definition of minorities in the United States to include Hispanics, who, even then, were close to being the largest minority group and were the fastest growing. Until that point, my academic career at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) had been devoted to genetic and therapeutic studies in rheumatoid arthritis. Applying for these funds represented a departure of my initial efforts, but one that could get me back to my original motivation to become a rheumatologist.

In this endeavor, I was strongly encouraged to respond to this RFA by the then Division Director, Dr. William Koopman, a distinguished rheumatologist who served as the ACR president between 1996 and 1997. I remember Bill saying, half-jokingly of course, “Chela, you can become the next Lupus Queen,” to which I simply replied with a smile. I’m not sure who, among the many distinguished women who have preceded me, carries such a title! Obviously, I have not become the Lupus Queen, but I can honestly say that, because of the Lupus in Minorities: Nature versus Nurture (LUMINA) study, I have gained some degree of recognition within the international community of lupus researchers, certainly beyond what I could have envisioned as a medical student in Perú.

To develop a research study on lupus with a significant number of Hispanic subjects, I called upon a former UAB faculty member, Dr. John Reveille of the University of Texas Houston (UTH). Working in Houston, John had firsthand experience with seriously ill Hispanic patients with lupus, and his enthusiastic support was crucial for our successful grant application submission. Of course, the beginnings of the study were somewhat rocky. After the initial and justified exhilaration of receiving the grant came the arduous job of organizing the study for which, in retrospect, I can say we were not fully prepared. As occurs in parenthood, we learned a lot on the job itself (what instruments to use, what variables to include, the frequency of the study visits, what laboratory tests we could afford, and the like, and more importantly, how to best use this resource to advance our knowledge of lupus, once constituted).

In April 1994, patient enrollment began simultaneously in Alabama and Texas. A few years later, we were told that LUMINA did not quite represent the Hispanic population in the United States and that we should include a Puerto Rican patient group. This sort of pressure/directive was in fact instrumental not only in enlarging our cohort but also in teaming us up with a young and energetic investigator from the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), Dr. Luis Vilá, with whom I have developed a very close relationship. By late 2008, the LUMINA cohort had over 600 patients (220 Hispanics from Texas [n=118] and the island of Puerto Rico [(n=102], and African Americans [n = 234] and Caucasians [n=181] from both Alabama and Texas) and had contributed to the literature quite extensively (75 published original research papers and numerous abstracts as well as editorials, reviews, and commentaries); about 75% of the African Americans and Caucasians were recruited in Alabama, while the remaining 25% were recruited in Texas. In all instances, these were patients with relatively recent-onset lupus (five years of disease duration as the maximum) being cared for their disease (or presenting for the first time to be cared for) either at UAB, UTH, or UPR.

The next best thing that happened to LUMINA is the support we obtained from an organization called Rheuminations (initially thru the Cornell Lupus Center of Excellence), with which I was able to fund several Latin American and Spaniard research fellows. Rheuminations is a nonprofit private foundation created by Katherine and Arnie Snider with the specific goal of improving the lives of patients with lupus and those who care for them through education and research. By the time I retired in 2009, Rheuminations had developed the STELLAR program (Supporting Training Efforts in Lupus for Latin American Rheumatologists) at UAB, and through it I was able to fund the last four of 10 research fellows who worked with me in the LUMINA cohort. These fellows brought enthusiasm and dedication as well as many new ideas that we explored with the expert and unconditional guidance of Dr. Jerry McGwin from Epidemiology at UAB. These fellows were from Mexico (Drs. América Uribe, Mónica Fernández, and Sergio Durán), Argentina (Drs. Sergio Toloza, Ana Bertoli, and Guillermo Pons-Estel), Chile (Dr. Paula Burgos), Colombia (Dr. Luis Gonzales), Perú (Dr. Rosa Andrade), and Spain (Dr. Jaime Calvo-Alén).

The fellows in the STELLAR program and the ones funded through the Cornell Lupus Center of Excellence were all young and eager to prove themselves as investigators. Without exception, they worked long hours and demonstrated great commitment to the study, developed their own research projects utilizing the database from the cohort, and wrote and rewrote their manuscripts numerous times—a significant challenge, not only because of their relative inexperience in this form of writing, but also because they, like me, have Spanish as their first language. These fellows, along with the clinical fellows that worked in the cohort (Drs. Maria Danila and Sumapa Chaiamnuay), made my last years at UAB incredibly rewarding. I will treasure the experience with them and consider it the highlight of my academic career at UAB.

The main contributions that the LUMINA cohort has made to advance our knowledge about lupus can be summarized as follows:

1) We have called attention to the seriousness of lupus among Hispanics (primarily of Native American background), which in many ways mirrors the disease observed in African Americans. Of note is the similar frequency of renal disease (62%), which contrasts with the frequency observed among Caucasians and Puerto Rican Hispanics (about 25% to 26%), damage accrual (more rapid accrual and of greater magnitude), disease activity (greater), and survival (diminished). Although it would be easy to ascribe these findings to the presence of ancestral Native American genes among these Hispanic patients, when socioeconomic variables are taken into consideration, some of the differences observed between the ethnic groups can be accounted for by socioeconomic factors.

I hope, therefore, that by focusing attention on the seriousness of lupus among persons of Hispanic descent … we will meet a growing challenge in public health.

In the case of disease activity, ethnicity remains an explanatory variable when examining factors that contribute to disease activity early in the course of the disease but not when examining those that contribute to disease activity over time. In the case of renal disease occurrence, by contrast, ancestral genes and the combination of ancestral genes and socioeconomic factors contribute to the increased predisposition to renal disease observed among Texan Hispanics and African Americans, probably as a result of difficulties in accessing healthcare and lower response rates to currently available therapies. Other observations also support the importance of socioeconomic factors as important modulators of clinical events in lupus; for example, even though adverse pregnancy outcomes were observed more frequently among the Texan Hispanics and the African Americans than among the Caucasians and Puerto Rican Hispanics, it was education (low level) rather than ethnic group the variable that remained in multivariable explanatory models.1

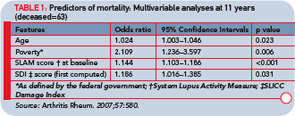

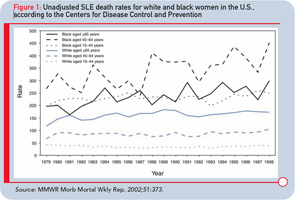

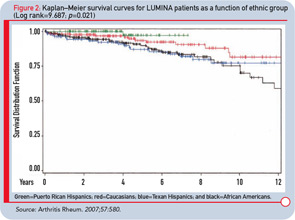

2) We have demonstrated the importance of socioeconomic factors as contributors to survival in lupus. If we examine the most recent mortality data in lupus from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one observes the disparate curves between African-American and white patients (see Figure 1); importantly, the mortality rates for African Americans seem to have increased over the last few years. Unfortunately, no data for Hispanics are noted in this publication. In univariate analyses, we have also shown that the survival curves are quite disparate (see Figure 2), with African Americans and Hispanics from Texas, exhibiting lower survival than the Caucasians and Puerto Rican Hispanics. However, in multivariable analyses (repeatedly conducted over the years), we have shown that it is poverty and not ethnicity that is an independent contributor to a diminished survival (see Table 1).2–5

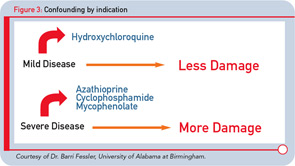

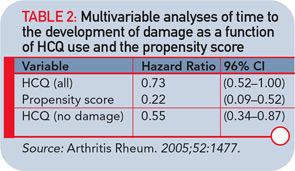

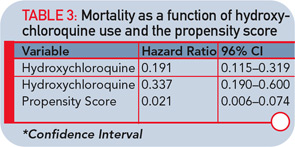

3) The third salient contribution of LUMINA to the literature relates to the beneficial effects of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in terms of damage accrual (in general and in specific domains of the damage index) and survival. I should note that this area of investigation was first proposed by a young UAB colleague and LUMINA co-investigator, Dr. Barri Fessler. She approached me some time ago in the 1990s with the idea of exploring the possible protective effect of HCQ in lupus. Knowing that HCQ, by and large, was prescribed primarily to patients with mild to moderate lupus (confounding by indication, see Figure 3), I told her that I was unconvinced about the merits of such exploratory analyses but that she should go ahead. In fact, after adjusting for variables that differed between HCQ users and nonusers with propensity score analysis (quite a novelty in rheumatology at that time), such a protective effect was indeed demonstrated, proving me to be wrong in my preconceived assumption (see Table 2).

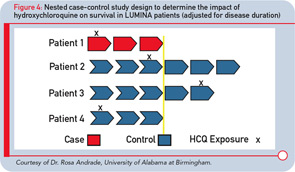

Subsequently, additional exploratory analyses were conducted by some of the research fellows, demonstrating that this protective effect is particularly evident in the renal and integument domains. Finally, using an elegant case (death)–control (alive) analyses adjusted for time in the cohort (see Figure 4), we were also able to demonstrate that HCQ has a protective effect on survival after adjusting for confounding variables (see Table 3).6–9 Our publication spearheaded similar analyses in the GLADEL cohort (Latin American inception lupus cohort), which corroborated our findings.

These are, by no means, all the relevant contributions the LUMINA cohort has made to our literature. I cannot list them all here, but a literature search will quickly take the reader to our many publications. Suffice to say at this point that, in the words of Dr. Suzanne Serrate-Sztein from NIAMS, the LUMINA cohort database can be considered “a national resource.” In fact, we are happy to share these data with doctoral students and fellows if they wish to pursue as yet to be answered research questions.

For now, I am still working closely with the STELLAR fellows as they develop their own cohorts and studies in their native countries (with the continued support of Rheuminations) while simultaneously assisting our benefactor with the Lupus registry she is currently supporting.

I could not be more excited to see the progress of this research as it moves forward, especially as it incorporates other countries and parts of the world. This is more than enough to keep me intellectually challenged and active in my retirement years!

The story of the young woman at the beginning of this piece needn’t have ended so tragically. I hope, therefore, that by focusing attention on the seriousness of lupus among persons of Hispanic descent, especially those with a high proportion of Native American genes, we will meet a growing challenge in public health and improve the outcome of patients with this serious and disabling disease.

The root of the word LUMINA is light. Our study is shedding light on this important area, and the scientific progress has been significant and I hope transformative. Until the care of all patients with lupus is the same, however, I believe that much more light is needed, and I want to be there to keep it shining.

Dr. Alarcón is professor emeritus of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

References

- Alarcón GS. Lessons from LUMINA: A multiethnic US cohort. Lupus. 2008;17:971-976.

- Alarcón GS, McGwin G Jr, Bastian HM, et al. LUMINA Study Group Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VII [correction of VIII]. Predictors of early mortality in the LUMINA cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:191-202.

- Fernández M, Alarcón GS, Calvo-Alén J, et al. A multiethnic, multicenter cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as a model for the study of ethnic disparities in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:576-584.

- Durán S, González LA, Alarcón GS. Damage, accelerated atherosclerosis, and mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Lessons from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort. J Clin Rheum. 2007;13: 350-353.

- Durán S, Apte M, Alarcón GS, LUMINA Study Group. Poverty, not ethnicity, accounts for the differential mortality rates among lupus patients of various ethnic groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99: 1196-1198.

- Fessler BJ, Alarcón GS, McGwin G Jr, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: XVI. Association of hydroxychloroquine use with reduced risk of damage accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1473-1480.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, González LA, et al. Possible protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on delaying the occurrence of integument damage in lupus: LXXI, data from a multiethnic cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62: 393-400.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, McGwin G Jr, et al. Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on renal damage in patients with lupus nephritis: LXV, data from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009; 61:830-839.

- Alarcón GS, McGwin G, Bertoli AM, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on the survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA L). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1168-1172.