After my editorials on coaching, I was going to give sports a rest and move on to more weighty topics worthy of a medical magazine. The inspiration well was also dry. The European Cup was over. Tiger was out for the season. The sports section was dreary, as rap sheets and tox screens crowded away the box scores.

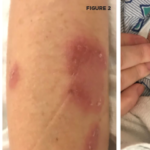

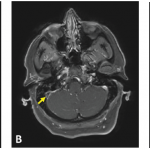

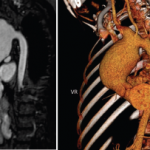

On the verge of describing a diagnostic dilemma I encountered in clinic (trust me, a real puzzler), I saw a sports story I could not resist. As the news media reported endlessly and breathlessly, Sanya Richards, winner of the U.S. Olympic trials in the 400-meter dash, has Behçet’s disease, a serious and rare affliction which nevertheless did not prevent a rousing victory.

As a human interest story, the account of Richards has the requisite stuff: a dire diagnosis, triumph over adversity, and a saga of personal courage. This combo is a journalistic trifecta to keep any sports fan transfixed in front of the TV as Richards’ exploits enfold.

Because Behçet’s is in rheumatology’s bailiwick, I was happy to have the media’s spotlight shine on one of our diseases, according it its fifteen minutes of fame. Furthermore, since therapy had seemingly restored Richards to world-class health, I could think of no better recommendation of our specialty’s skill than the sight of Richards beaming on the winner’s stand.

Interest (and Press) for Rheumatology

While I thought that this was nifty story, I had a sense of discomfort for, you see, I have heard it before. Consider for a moment, the following athletes and their diseases. Wilma Rudolph, the winner of the three gold medals in the 1960 Olympics, had both polio and scarlet fever as a child. Her bio says that she wore heavy metal braces and that her mother massaged her legs to stimulate recovery.

Another heroine with immune system problems is Gail Devers, the only woman to win consecutive Olympic 100-meter dashes. Devers had Graves’ disease with muscle involvement so severe that her doctors were planning to amputate her feet. Finally, there is Michelle Akers. Once named soccer player of the century, Akers suffered from the debilitating effects of chronic fatigue syndrome, a possible complication of mononucleosis, that left her so exhausted and depleted she needed intravenous fluids to finish her matches.

Given the way athletes beat up their bodies, I expect them to have more than their share of musculoskeletal problems—popped tendons, shredded ligaments, and cracked bones. The immune problems of the athletes, however, are remarkable in their variety and severity.