In rheumatology, the diagnosis may be apparent as soon as I shake a patient’s hand or scan the face or extremities for clues. Some physical signs are pathognomonic, that is, specific for only one disease. Osteoarthritis spares the knuckles, but gradually enlarges the middle and distal joints of the fingers. A heliotrope rash—a faint purplish swelling around the eye—is specific for the immunologic muscle disease, dermatomyositis. The thickened skin of scleroderma, the facial rash of lupus, the destructive saddle nose deformity of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), are rare but specific signs of their respective diseases.

If at first the diagnosis eludes me, a careful review of the history and a good physical exam with a dash of focused lab usually makes the obscure apparent.

But when I still don’t know the diagnosis at my follow-up visit, sometimes I don’t know what’s wrong for months, even years. Sure, doctors take pride in their successes, but the mystery cases, the patients who remain unwell and undiagnosed even after a second opinion, are not uncommon. Or, as Ron Anderson, MD, a prominent Boston rheumatologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, once confided to a startled group of medical students and residents during a case presentation, “That disease saw me long before I saw it.”

In most of these unknown cases, it’s not that I’m completely lost. I know in a general sense that there is an inflammatory disease present. I know that there doesn’t appear to be cancer in the background, or infection. I have a lengthy list of conditions that the patient does not have. But one of my most difficult tasks when I sit down with a patient at a follow-up visit is to take a deep breath, adjust my glasses and admit that I don’t know what’s wrong.

A Long & Winding Road

Such was the case for Leon Woodle, a 58-year-old pig farmer I consulted on some years ago. Leon’s history was a long and rocky road. He was a chronic hepatitis C virus carrier—presumably from shooting up heroin in his 20s, or maybe from the blood transfusions he required after a head-on motor vehicle collision some years later. His serotype, the specific subtype of hepatitis C virus he was infected with, was unlikely to permanently damage his liver, so his doctors had held off on antiviral medications. That was fine with Leon, because treatment with alpha-interferon and ribovarin is often associated with significant side effects and doesn’t always cure the disease.

Five years before my consultation, Leon had developed diabetes and ignored it until diabetic eye complications required laser surgery and a painful diabetic neuropathy affected his feet. He smoked a pack of cigarettes a day and drank “whatever.” He’d been banged up and run over; the three surgeries on his back and two on his left knee had left him with a permanent limp. On his medical questionnaire he’d checked off hypertension, high cholesterol and cataracts, and circled depression with the notation, “Wouldn’t you be?”

I strolled past the partially open door to his exam room. He was a big bear of a man, unshaven, his hair a greasy black tangle. A faded plaid wool shirt hung loosely over his chest and flowed over faded blue jeans. His grimy steel-toed work-boots were half-unlaced. The smell of a wood stove drifted into the hallway.

According to the chart, his current weight of 238 lbs. was down 18 lbs. from six months before. Low-grade fevers and sweats, sometime severe enough to cause him to change his T-shirt, were occurring episodically. His hands hurt. His back and left knee ached. In broken cursive, under chief complaint he’d written, “Feel like sh*t, think I’m dying.”

I turned the page to the laboratory studies his family doctor had ordered. Two liver enzymes, AST and ALT, were elevated, but in line with his history of chronic hepatitis C. Several other liver tests, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin were in the normal range. He was borderline anemic. Lyme and syphilis tests were negative.

Under immunologic testing, his primary had pulled the trigger and ordered every test under the sun. And the problem was, most everything was borderline abnormal. In complex cases such as Leon Woodle’s, this phenomenon, diarrhea ordering or scattergun ordering, is inversely related to the likelihood of arriving at the correct diagnosis. Sick people have sick lab results. The more you order, the more abnormal labs pop up. Invariably, additional labs and X-rays are ordered to follow up on the abnormal tests, but with each pull on the slot machine lever, the chances of making the correct diagnosis become more random, less considered.

Patients, for some reason, often admire this “He ordered every test in the book” approach. Never mind that most of the abnormal lab results were irrelevant. For example, Leon’s uric acid level was elevated but nothing in his history suggested gout, so why order the test? A rheumatoid factor was up, but positive rheumatoid factors are not only seen in rheumatoid arthritis, but are also triggered by the immune response to … hepatitis C. Antinuclear antibodies? Leon’s were borderline high, but there was nothing in his history to suggest lupus.

Looking up at the clock over the exam room door, I brought myself back to the problem at hand. Start over. When all else fails, the saying goes, examine the patient. If there was an answer to Leon’s illness in the referral notes and labs, he wouldn’t be here. Start over.

Start at the Beginning

The first thing I noticed when I shook Leon’s hand was that, at the corner of his elbow, folded neatly at the crease, was a completed New York Times crossword puzzle, in ink. Put that into the mix, I thought. He cautiously extended his hand. The fingers were cracked and calloused. Subtle swelling was present in the second knuckle. The right forearm was bruised. “Leon Woodle. Everyone calls me Leon. Thanks for not gripping too hard, Doc.” He noticed the internal medicine resident hovering at the door. Some patients are reluctant to have another stranger sit in on their consultation, but Leon was comfortable with the attention. “Come on in. Two heads are better than one.”

If at first the diagnosis eludes me, a careful review of the history & a good physical exam with a dash of focused lab usually makes the obscure apparent.

With a look of relief, the resident entered and leaned against the sink. For the past week, this particular third-year resident, “Dr. Litmus,” had shown that she was a cut above most of her classmates who rotated through my office. She was comfortable with patients, bright, logical and empathetic, and I was hoping to interest her in applying for a fellowship in rheumatology rather than her stated interest in cardiology.

I asked Leon how long he’d lived in Maine. “Five years. Came back to live with my mother. Help out with the farm. My opportunities for making a living in New Jersey were, what I would call, limited.” He hesitated for a moment and added, “Prison will do that.”

“What’s it like working with pigs?” I asked.

“Yeah … You know, pigs are pigs. They eat most anything, and as long as you shovel their sh*t and keep their shed clean, they’re pretty content. Seasonally, I tar driveways. Money’s actually pretty good. Keeps me busy.”

“So what was the first thing you noticed when your health changed?” I asked.

“Fatigue. That was maybe six months ago. The heat and I don’t agree, so when I began to get the sweats at night, and it was summer, I didn’t think much of it at first. But I got so bone tired, it was all I could do to drag myself out of bed.” He stopped for a moment and scratched at his elbow. “I think the swelling in my right hand came next. This one was first,” he pointed to the second knuckle, “then this one.” The fourth finger’s middle joint was reddened and boggy.

“And the weight loss?” I was jotting down notes, developing a timeline with arrows and question marks.

“Hard to say. I go up and down with the weather. Up in the winter, down in the summer. What did your scale say?”

“238.” I said.

“Winter, I get up to 250, sometimes 260. Probably dropped more weight this summer than usual. Appetite’s down. Bowels looser than usual, but I go through that sometimes, too. Got a nervous stomach.”

“Anything else?” I asked.

“Muscle aches. Strength is down. One night I took my temperature, and it was just over 100º. The whole deal is getting me down.”

As he spoke, I methodically palpated his neck for lymph node enlargement. There were a few tiny nodes, but none were particularly worrisome. In assessing whether lymph nodes are abnormal, I estimate whether they are larger than the fingernail on my ring finger, have a rubbery consistency or are attached to the adjacent soft tissue. Each of these findings suggests a possible malignancy. Leon’s lymph nodes were a little generous in size, but not pathologic.

I asked him to open his mouth. The faint smell of Listerine was present. The tonsils were unremarkable. Most of his teeth were missing, and the rest were rotten and loose. Then, on to the heart. I placed the stethoscope firmly on his upper chest to dampen the background scratching noise chest hair makes. A harsh, crescendo murmur was present at the edge of the upper sternum, and I asked Leon to stop breathing for a moment so that I could time the murmur during the cardiac cycle. I motioned the resident over and had her listen.

“Aortic valve,” Leon declared confidently. “Calcified, with two cusps instead of three, what the cardiologist called a bicuspid valve.” I’d forgotten about the Times crossword puzzle. The man was a sponge for medical jargon. “Told me not to worry about it, so I don’t. Suggested I repeat the 2-D echocardiogram in a year.”

“Any new sexual partners?” the resident asked.

For a moment there was silence. Then, “My pecker has gone on strike. Not much left there.”

“I’m sorry,” said the resident.

“Me too,” Leon shrugged.

“Any shortness of breath? New cough?” I asked, moving on to the lungs.

“Nah, nothing but me and my chronic smoker’s cough. I clear out the junk first thing in the morning, and then I’m good to go for the rest of the day.”

Moving on to the posterior chest, I heard a faint wheeze in the right mid-lung field, but not in the left. After placing one finger on the lower posterior chest wall, I percussed the lower lung fields—an old-fashioned way of assessing whether fluid is present in the chest. The tapping had a reassuring normal hollow ring. A flat tone would have suggested a collection of fluid surrounding the lung.

The abdomen was normal. Even the liver, chronically infected with hepatitis C, was nontender and of normal size and consistency. The left knee was crisscrossed with scars and held a cup of fluid. Leon winced slightly when I flexed and extended the joint. “Orthopedics says I can get a new knee anytime I’m ready. The inner part is bone against bone.” He reached down and massaged the damaged knee. “If you’ve got time, I could use a cortisone shot. Seems to hold me for four or five months.”

“Sure,” I replied. “Let me have Joanne come in and set up for that and I’ll be back in a few minutes.” The medical student and I walked back to my office. “Well?” I asked the resident.

Follow the Clues

“Did you get a chance to review the lab?”

“I did. Most of it was abnormal.”

“And? What do you think? You heard the story? Want to give me your top four in your differential diagnoses?”

The resident cleared her throat. She ploughed ahead. “Okay. I think he has more than one diagnosis. The knee is osteoarthritis. It’s a mechanically damaged joint, and the cortisone shot should help, at least for now.”

“Okay, I’ll give you that. Osteoarthritis is a safe bet. And that probably explains his back pain as well, right? But he has a whole lot going on besides osteoarthritis. Go on.”

“Well, the fingers are swollen and stiff, and he has a rheumatoid factor in his blood. I’ve heard that sometimes RA is systemic; people can have fevers with it, as well as fatigue.”

“True,” I replied. “Maybe he has RA, but it’s more or less restricted to his right hand, and RA is usually symmetric. Think about his other symptoms: muscle aches, weight loss, sweats. Any other thoughts?

No one goes to the grave with an undiagnosed disease without a wallop of steroids.

“Smoker. Chronic cough. He could have lung cancer. If he hasn’t had a chest X-ray [CXR] lately, that would be on my checklist.”

“Good. I’m glad you’re widening your differential diagnosis beyond classical rheumatology. Lung cancer can trigger a paraneoplastic syndrome with swollen joints and fevers. So a CXR would be No. 1 on Willy Sutton’s list.”

“Willy Sutton?” She raised an eyebrow.

“The famous bank robber,” I answered. “Someone asked him why he robbed banks, and Willie supposedly said, ‘That’s where the money is.’ Chest X-ray, good thought.”

“But if the CXR is clean,” the resident added, “I keep thinking this guy smells like HIV. He’s losing weight, no appetite, weak, sweats; lymph nodes are on the juicy side. I’d say HIV from the heroin or the blood transfusion or an old sexual partner.”

“An HIV test (which, frankly, hadn’t crossed my mind) is a great idea,” I agreed. “But let’s say his CXR is normal and his HIV test is negative, I’m going to add hepatitis C vasculitis and hemochromatosis to the list.”

“Of course!” The resident could barely contain herself, she was so excited. “That is so cool! To evaluate for hepatitis C vasculitis, we should pick up a viral load for hepatitis C and cryoglobulins, and hemochromatosis is a genetic iron overload disorder.” She looked up and to the right, as if she were channeling a textbook: “Iron is toxic to the liver and can cause inflammatory arthritis and injure the pancreas, leading to diabetes. Over time, it can affect the function of the pituitary gland in the brain and trigger profound fatigue, and impotence. Eventually, it’s fatal due to liver or heart failure. Mr. Woodle has to have hemochromatosis,” she declared.

A Week Later

Only he didn’t. At my follow-up visit with Leon a week later, I reviewed the normal CXR, normal iron studies, clean HIV test, a minimal hepatitis C viral load and negative cryoglobulins. His joint swelling had spread to the other hand, and he’d lost another 2 lbs. The poor guy could barely make a fist or wipe himself after toileting, so I began 15 mg of prednisone, telling him that between the positive rheumatoid factor and the symmetry of inflammation, his illness probably represented rheumatoid arthritis. He took the prescription, and when I called him a week later, he said that he was about 60% better. But the diagnosis didn’t sit well with me, like I was trying to cram the diagnosis of RA into a pair of shoes two sizes too small.

When I ran into the resident at hospital Grand Rounds several weeks later, she remembered the pig farmer. I reviewed his partial response to prednisone and my tentative diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

“Tentative diagnosis?” she asked. I admitted I wasn’t sure. She pushed a stray hair up and over her ear and did that odd up-and-out gaze to the right I’d noticed before. She was turning over the possibilities. “Blood cultures?” she finally asked. “It’s funny how a case sticks with you. The guy had horrible teeth. Maybe one of the more indolent bacteria, say Strep viridans, got into his circulation, and that heart murmur we heard was due to an infection of the valve. Endocarditis; that would explain a lot.”

“I agree,” I answered, “but the blood cultures I drew last week are sterile. It’s possible he has a fastidious organism, like Coxiella burnetii.”

“Q fever!” She almost shouted out.

The diagnosis didn’t sit well with me, like I was trying to cram the diagnosis of RA into a pair of shoes two sizes too small.

“Right. It’s spread by contact with an infected animal, so by working on a pig farm, Mr. Woodle is at risk for the disease. Only Coxiella doesn’t usually grow on blood cultures. I’m setting him up with infectious disease. If it’s Coxiella, I’m sure they can prove it’s the culprit. If it’s not endocarditis, maybe they can come up with another chronic infection to explain why he’s wasting away.”

Back to the Drawing Board

Only they didn’t. Although the consult note I received from ID two weeks later was thoughtful and thorough, nothing panned out. Thank goodness the malaria smear was negative, I smiled to myself as I reviewed the reams of normal lab ID had ordered. For a homebody who hadn’t traveled outside of Maine for the past five years, the only way Leon could have developed malaria would have been if a mosquito had snuck into a plane in Africa, been flushed alive down the plane’s toilet, and the toilet contents released as the plane passed overhead, misting Leon as he came out of the barn.

At our follow-up visit, Leon was down another 10 lbs. His hands were slightly more limber, but his elbows and ankles were now tender and swollen. For the previous seven nights, he’d suffered drenching sweats and fevers. He groaned as he eased himself into the exam chair. “Think I got cancer, doc?” he asked.

I met his eyes. “I don’t know,” I answered. “How are your blood sugars?”

“Whatever has dug in, it’s nearly cured my diabetes. I’m wasting away, and my primary has cut down my insulin and cut down my insulin to the point I stopped it altogether last week. I’m just about useless. I stopped that new medication you added, the plaquenil. Diarrhea got bad. Maybe it’s a little better off. I don’t know. Had to let my driveway pavement business go this summer.”

I reexamined him. He was beginning to look like photos of President Lincoln. His flesh had a pasty, droopy quality to it. Fat and muscle were melting away. Besides the inflammatory arthritis, his exam was essentially unchanged, except, I kept coming back to a hint of fullness beneath his right armpit. Was that a palpable lymph node? “Mr. Woodle,” I decided, “I’m admitting you today. We’ll schedule you for a CT scan of the chest and abdomen. If we find something suspicious, we’ll get it biopsied. If not, I’ll consult hematology; you may need a bone marrow aspiration.”

“Fine. Let’s get it done. I’m no good this way.”

Maybe I’ll be lucky, I thought, realizing with a start that I’d drifted into the same vague differential diagnostic morass I’d criticized his primary doctor for. Still, maybe I’ll be lucky.

More Tests

Only I wasn’t. The CT scans showed some background noise; the pancreas was scarred (probably the result of his past heavy drinking), and the spleen was a little generous in size, but nothing abnormal enough to biopsy. Hematology initially balked at performing the bone marrow. Dr. Hedlund argued, justifiably, that the patient’s anemia was secondary to his inflammatory illness and that the flow cytometry they performed on his blood essentially ruled out leukemia. There was almost no chance a bone marrow would be diagnostic of a specific disease.

But I pushed for the bone marrow based on a hunch. Mr. Woodle’s case stayed with me after hours. I found myself drifting back to it at night and sometimes when I awoke in the morning. I reviewed his clinical course, the nonspecific lab and turned over the possibilities in my mind. None of the possible diagnoses fit. Even the extraordinarily rare diseases I’d encountered during the past several decades—adult-onset Still’s disease, GPA, Behçet’s syndrome—had characteristic findings Mr. Woodle lacked. During a follow-up phone call with Dr. Hedlund in hematology, I limply suggested that sarcoidosis can hide out in the bone marrow and be the cause of sweats and fevers, and muscle and joint pain.

“Sarcoidosis?” Dr. Hedlund repeated. “You think that with a normal chest X-ray, and an essentially normal chest, abdomen and pelvis CT scan that he has sarcoidosis?”

I could hear her tapping her fingers in the background. She wanted to get off the phone and do something productive. “Yes,” I heard myself saying. “Isolated granulomas in the bone marrow have been reported with sarcoidosis.”

“Okay. Fine. I’ll do the bone marrow tomorrow morning.”

The bone marrow was not diagnostic of anything. Burned that bridge, I thought to myself. That’s the last time I’ll be able to convince hematology to perform a procedure they don’t think is indicated.

After his discharge, Leon’s weight dipped below 170 lbs. (from 238 at our first visit, four months before). I continued the prednisone. Without it, he couldn’t get out of bed, with it he could dress himself and sit on the sofa and watch TV. I repeated the stool cultures. The most experienced hospital lab tech pored through the three morning stool samples looking for parasites. Nothing. A gastroenterologist performed a colonoscopy and this was disappointingly “clean as a whistle.”

After a while, Leon got tired of coming to see me. He missed one appointment and then another. I didn’t blame him. Despite the hepatitis C, I suspected he’d said, to hell with it, and gone back to heavy drinking, maybe even reconnected with his old buddies from his heroin days.

One frigid morning in December—seven months after our initial visit, I got a call from Maine Medical Center. Leon had been admitted through the ER four days previously, at death’s door. Could I come and take a look at him?

All through morning office hours, my mind kept returning to Leon’s case. Maybe the answer had been staring at me the entire time. When my last patient of the morning was a no show, I decided to visit Leon over lunch. My first stop: radiology. In the faint white glow of the view box, his chest X-ray from the ER showed why he couldn’t breathe; the right side of his lung was obscured by fluid. The radiologist walked me through the abdominal and chest CT scan ordered on Day 2. The bowels were sitting in a liter or more of free fluid in the abdomen, but there was no sign of an abscess or cancer.

“What’s that?” I pointed to a hazy patch outside the upper right chest beneath the shoulder.

“Lymph node biopsy site. Pathology must have the specimen.” The radiologist turned his head toward me, his face eerily glowing from the back-lighting. “Must be cancer.”

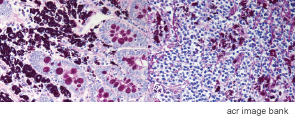

I trudged down the hall. It makes sense that Leon Woodle has cancer. Sometimes we never find the primary source; eventually a lymph node metastasis is the only evidence. At least we have tissue; maybe it’s a treatable form of lymphoma. Inside the pathology office, Dr. Vanderburgh located the lymph node biopsy slides and we sat down at a double-headed microscope. He pointed out clusters of neutrophils and lymphocytes, mast cells and a sprinkling of eosinophils. “It’s an intense inflammatory reaction. No granulomas. No signs of malignant cells.”

“No signs of cancer cells? Seriously?” I asked. “No cancer?”

He looked at me sullenly, stone-faced. “I’m a pathologist. Seriously, there is no cancer.”

Up on the floor, I cracked open Leon’s chart and dug in. He’d received his first dose of antibiotics in the ER after a liter and a half of cloudy pleural fluid was aspirated from his chest, the abdominal fluid sampled, and blood and urine cultures collected. But he wasn’t responding. The fever curve on the nursing graphs showed a hectic graph with temperature spikes over 103. Nothing was growing out on culture. It was a familiar story.

Last-Ditch Efforts

When I cracked open the door to Leon’s room, it was clear he was dying. Shrunken into his bed, belly distended, the fingers of both hands were puffy and red. He’ll carry his unknown inflammatory arthritis to the grave, I thought. The continuous shhhhhing of a nonrebreathing mask gently filled the room like drifting snow. I stood at the head of the bed, painfully aware that Leon was about to join my list of patients who died of an unknown disease. I reached over and patted his wrist. I felt like I should apologize for failing him. It felt awkward. I wasn’t sure how deeply he was comatose, so I leaned over and whispered in his ear, “Keep fighting, Leon. Don’t let go.”

But I was not optimistic. I checked the chart. Pasted on the inside cover was his NO CODE request. Makes sense, I thought. He’d had enough. His nurse entered the room to adjust the IV antibiotic infusion rate. I asked her if she could call lab and have them draw a red-top tube for me and to spin it down. I pulled my 3×5 notebook from my shirt pocket and wrote, “Don’t forget to pick up Leon Woodle’s red-top tube.” It will join a dozen or so red-topped tubes in my office freezer, awaiting the day when a new case report draws my attention and I draw off an aliquot of fluid to run a newly developed test. Someday, I may know what Leon died of.

Even as I accepted that I may not know the diagnosis, that I might never know Leon Woodle’s diagnosis, I continued to sift through the evidence. It’s not cancer. There is no clear evidence for infection. An atypical presentation of one of my diseases? Maybe. It’s nearly impossible to prove a negative. He’s dying; maybe I should order a pulse dose of steroids? Hey, at this point what harm will that do? I clicked my pen and wrote the order: 1,000 mg Solu-Medrol in 100 cc D5W. Infuse now. There is an old saying in rheumatology: No one goes to the grave with an undiagnosed disease without a wallop of steroids.

The Clues Come Together

Leon’s eyes flickered open and settled on me. He groaned as he shifted his head on the pillow. The faintest whiff of fresh manure flowed my way. Pig farmer. Polyarthritis. Weight loss. Fevers. I cocked my head and scratched behind my ear. Diabetes, hepatitis C, diarrhea, pleural effusions, pericardial effusions, ascites, lymph node enlargement. It’s not infection. Maybe it is infection, and he’s not on the right antibiotic? It’s not immunologic. Maybe it is immunologic, and he needs pulse steroids.

My pen hovered over the pulse steroid order. Sign it, notify pharmacy, get it hung, hope for a response. I signed the order. A simple question came to mind. It came from, where? Why not Whipple’s disease? Momentarily, I could recall almost nothing about Whipple’s disease. Then, I seemed to remember, hadn’t I seen it on an extended list of rare causes of diarrhea and inflammatory arthritis? I crossed the order off, closed the chart, and jogged upstairs to the library.

Whipple’s Disease

Cracking open a rheumatology text, I reviewed what little is known about the disease. At the time the text was written, I flipped back to the inside cover, as of 1994, there were only 300 or so cases reported in the world’s literature. I learned that Whipple’s disease is an infection that originates in the small bowel. An extraordinarily fastidious organism, Tropheryma whipplei, can’t be cultured from stool samples. It can’t be grown from the blood. As yet, there was no antibody test to definitively confirm the diagnosis. But it can be seen on microscopy, I read on, if the proper stain, a PAS stain (Periodic acid-Schiff), is applied to the biopsy material. Over time, in untreated cases, the infection spreads inexorably from the GI tract to adjacent lymph nodes, and, once established, it slowly overwhelms the immune system and escapes into the general circulation. Arthritis, sometimes mimicking rheumatoid arthritis, may be present. Untreated, the disease is usually fatal.

My eyes settled on the last paragraph: The disease may be more common in workers exposed to manure or raw sewage. Treatment with corticosteroids is generally ineffective. Treatment with the antibiotic Bactrim is usually curative.

I closed the text and called pathology. No, the biopsy hadn’t been PAS stained. Yes, they could reprocess additional lymph tissue and stain the samples with PAS. The slides should be ready tomorrow. For the first time in seven months, I felt confident in my opinion. The shoes fit. It had to be Whipple’s disease.

There was one small problem. Consulting physicians don’t usually over-ride orders, particularly antibiotic orders, written by the admitting attending doctor. Leon Woodle was slipping away on a cocktail of antibiotics, appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics, effective against a host of infections, but not against this particular infection, not against Tropheryma whipplei. The attending on the case was reluctant to discontinue the current antibiotics. I had no direct evidence this was Whipple’s and was reminded that the current combination of IV antibiotics was usually superior to the older drug Bactrim for a wide variety of infections.

“Are you sure you don’t want to give him a mega-dose of IV steroids?” the attending asked.

“No. Do me a favor. If you don’t want to stop the current antibiotics, add IV Bactrim tonight. Give me a day, and if the slides don’t show evidence for Whipple’s we can stop the Bactrim. Can you do that?” I held my breath.

The next morning, after a second dose of Bactrim, Leon’s fever broke. Art Vanderburgh, MD, the taciturn pathologist, called and wanted me to take a look at the slides. The PAS stains were positive for Whipple’s. Everywhere we looked: the lymph node, the fluid from around the heart and lungs, every sample he restained was flooded with the organism. He marveled at how the organism, now so obvious, could have remained hidden so long.

The Road to Recovery

And ever so slowly, Leon made headway. His arthritis melted away and the diarrhea resolved. Follow-up scans showed that the fluid around his heart and lungs and the ascites in his abdomen were in full retreat. On the day his oxygen was discontinued, he asked for a pass to go outside to smoke a cigarette. His strength had returned. He’d had enough of hospitals. He was going outside, regardless. He was a changed man—but not that changed.

The Great Imposters

We call them zebras—rare diseases hiding in plain sight. They are the great imposters, mimicking everyday infections, cancer or autoimmune disease. And they keep me sharp, thinking, reviewing, adjusting my differential diagnosis when at the end of a consult, it just doesn’t add up. On the day Leon Woodle was discharged, the lab technician handed me the extra red-top tube of spun-down blood I’d requested. As a mystery solved, I decided to give it to Leon, who appreciated the fact that he was still alive. “You never know,” he informed me, “when Tropheryma whipplei might appear in a Times crossword puzzle.”

I wrote out the name of the causative organism of Whipple’s disease on the tube. We both agreed we’d never forget the spelling. I know he won’t.

Charles Radis, DO, is a rheumatologist in Portland, Maine, and director of clinical research for Rheumatology Associates.

Fast Facts: Whipple’s Disease

- Originates in the small bowel;

- Tropheryma whipplei can’t be cultured from stool samples or grown from blood;

- There’s no antibody test to definitively confirm the diagnosis;

- It can be seen on microscopy if the proper stain, a PAS (Periodic acid-Schiff) stain, is applied to the biopsy material;

- Untreated, the infection spreads from the GI tract to adjacent lymph nodes and slowly overwhelms the immune system;

- Arthritis, sometimes mimicking rheumatoid arthritis, may be present;

- It may be more common in workers exposed to manure or raw sewage;

- Untreated, the disease is usually fatal;

- Treatment with corticosteroids is generally ineffective; and

- Treatment with the antibiotic Bactrim is usually curative.