The overall approach to the treatment of psychogenic itch is to treat the underlying psychiatric disorder with anxiolytics, antidepressants and/or other neuroleptics. Patients typically need to see their primary physician regularly to develop strong therapeutic rapport. Once the patient is willing, a psychiatric referral is highly helpful, if not essential.

Idiopathic Itch

Idiopathic itch is defined as chronic itch in the absence of specific skin disease and lack of any evidence of underlying disease in the aforementioned categories.54 We include what has been described as pruritus of the elderly within this category because many aging conditions are not necessarily defined as distinct disease entities.55 Although the mechanism is unknown, it has been suggested that chronic generalized pruritus develops in response to gradual loss of skin barrier function, immunosenescence of the skin immune system and sensory neuropathy.56

Initial treatments can include restoring skin barrier function with cream- or ointment-based emollients and gentle atopic skin care. In severe cases, treatment by ‘soak and smear’ with topical steroids as well as steroid-sparing systemic agents such as azathioprine can be helpful.57 Similar to psychogenic itch, this is a diagnosis of exclusion and the astute physician must ensure no underlying systemic or inflammatory conditions are present.

Dermatologic (& Rheumatologic) Itch

Pruritus results most commonly from an inflammatory pathology in the skin. Atopic dermatitis, chronic urticaria, cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) and autoimmune skin conditions are often associated with chronic pruritus. Understanding the molecular basis of dermatologic itch will likely yield new targeted treatments. Recent studies have demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) (derived from keratinocytes) and IL-31 (derived from T helper type 2 cells), directly bind itch sensory neurons, suggesting that atopic itch may be targeted therapeutically (see Figure 1).58,59

In chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU), activation of mast cells has been implicated in the pathogenesis of itch via the binding of IgE onto cell surface FcεRIα receptors.60 Indeed, this has been supported by recent clinical trials demonstrating that omalizumab, an anti-FcεRIα monoclonal antibody, is highly effective in the treatment of CIU-associated itch.61 Collectively, these studies demonstrate that the identification of novel immunologic pathways that mediate itch hold great promise for future treatments (see Figure 1).

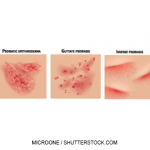

In terms of autoimmune and rheumatologic skin disease, psoriasis is the most common and affects 1–3% of the population. It presents with silvery, scaly plaques, generally on extensor surfaces.62 The prevalence of pruritus among patients with psoriasis ranges from 64–97%, and the intensity of itch severity correlates with the development of lesional plaques.63-67 Although T helper type 17 (Th17) cell responses have emerged as dominant mechanisms underlying psoriasis, the definitive pathway by which itch is elicited remains poorly defined.68,69 Notwithstanding this, itch is a key determinant of the efficacy of new biologic therapeutics in psoriasis.