A two-page, four-sided “folder” MDHAQ, generally only for new patients (or those new to a database), includes a standard medical history. A Microsoft Access program provides a report in a standard medical record format. Of course, the information must be reviewed by the doctor with a further careful history and physical examination, but 75% of the medical record note is provided by patient self-report, rather than written, dictated, or typed by the doctor. A self-report questionnaire provides considerably more accurate details about most (but not all) components of the medical history than dialog with a health professional, for most (but not all) patients.

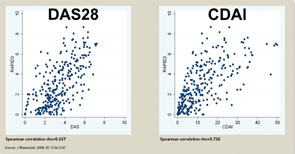

The three RA Core Data Set patient self-report scores for physical function, pain, and patient global estimate distinguish active from control treatments in clinical trials as efficiently as the three measures scored by a health professional—tender joints, swollen joints, and doctor global estimate—or laboratory tests.18-20 Therefore, RAPID3 is correlated with more traditional RA indices which include a formal joint count, Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28 and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) at levels of rho >0.6 (see Figure 5). These levels are higher than rho ~0.5 seen between ESR and C-reactive protein, indicating that RAPID3, DAS28, and CDAI address a similar construct in clinical trials and usual care settings.

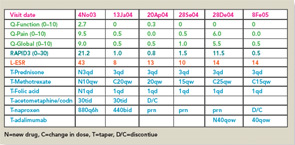

RAPID3 distinguishes active from control treatments in clinical trials as efficiently as DAS28 or CDAI, reflecting the individual measures. However, RAPID3 on an MDHAQ can be scored in about five seconds, compared with 90–120 seconds for a DAS28 or CDAI (see Figure 4).21 Flowsheets of patient self-report scores, laboratory test results, and medications (see Figure 6) allow presentation of the course of a patient at a glance (which is far more useful in busy clinical settings than pages or screens of narrative information) as “evidence-based rheumatology care.”

Evidence-Based Medicine in Usual Care

The term “evidence-based medicine” has been described as “derived from many sources beyond randomized clinical trials.”22 However, a hierarchy of levels of evidence lists randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses as the highest, and observational studies at lower levels, and the term “evidence-based medicine” often is applied only to data from clinical trials.23 Of course, clinical trials provide the most rigorous data to compare the efficacy of active versus control treatments over defined periods. Nonetheless, clinical trials have many pragmatic and intrinsic limitations, such as a short time frame, patient selection, inflexible dosages, and many others.24-27

Data from patients are more significant to predict mortality than laboratory tests, radiographs, and other high-technology data.

A view of “evidence-based medicine” as based only on clinical trials reflects a “biomedical model,” the dominant paradigm of 20th century medicine, to mimic a “reductionist” laboratory experiment, isolating a single variable for a research study. A biomedical model also views information from patients as “subjective” nonquantitative narratives, in contrast to “objective” high-technology data, and mind and body as separate in health and disease. The dominance of the biomedical model in contemporary rheumatology is reflected in rapid implementation of assays for DNA antibodies in the 1970s, and anticitrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) in the 2000s, while most rheumatologists have been slow to collect patient self-report questionnaires.28

I hope that more health professionals will adopt ‘evidence-based’ approaches to improve patient outcomes.

A biomedical model is most effective in acute diseases, but includes many limitations in chronic diseases, and the need for a complementary “biopsychosocial model” may be seen in studies of outcomes of RA.29 Data from patients are more significant to predict mortality than laboratory tests, radiographs, and other high-technology data. Socioeconomic status, reflecting actions of patients rather than health professionals, is highly significant in the incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of RA and many diseases, which can be explained only in small part by limited access to medical services. Much important knowledge concerning RA has been derived from observational research, not available from clinical trials, including frequent work disability and premature mortality,9 radiographic damage within the first two years,30 absence of long-term remission using traditional approaches,31 gastropathy associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs,32 better patient status at this time compared with previous decades,33 and many others. In analyses of the effects of methotrexate, the anchor drug for RA, observational data are more accurate than meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which underestimate efficacy, effectiveness, and safety.34 Patient questionnaire data can document improved status of patients in recent years compared with earlier periods (see Table 2).33 Such questionnaire data further documented that poor functional status and limited exercise predict premature mortality in the general nondiseased population in the range of smoking and hypertension (see Figure 7).35