Designua / shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—The path to the discovery of cortisone—a top-selling, important drug, with dozens of indications—was complicated by failure, false moves, desperation and obsession. The tale, recounted in the Philip Hench, MD, Memorial Lecture: Crossroads of History & Hope: Discovery & First Use of Cortisone for RA at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in October, is an odyssey with a cast of characters obsessed with the pursuit of the drug, said Eric Matteson, MD, emeritus professor of medicine in rheumatology at the Mayo Clinic.

The story centers on the man who figured most prominently in the discovery of cortisone: Edward Kendall, MSc, PhD. He was recognized for the achievement in 1950 with the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Dr. Kendall was a Mayo Clinic scientist who often didn’t get along well with his colleagues and, at the time, was not considered a great chemist and was “not a scholar,” according to one assessment. He was given to self-inflicted wounds: He twice announced in the early 1930s that he’d isolated cortin (later to be known as cortisone), only to be forced to retract the claim a year later each time.

“He faced the kind of embarrassing situation that would have ended the career of many scientists,” Dr. Matteson said.

The story began with a search for a treatment for Addison’s disease and is a gripping example of how the discovery of medications that eventually become cornerstones of care is far from inevitable. Dr. Matteson said such discoveries are often a matter of avoiding fatal hurdles through sheer will.

The Search

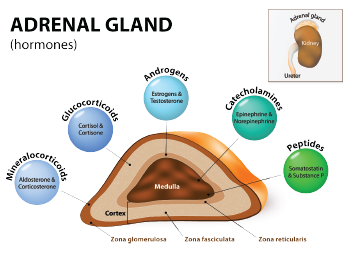

Dr. Kendall worked for many years on research involving the thyroid gland, discovering thyroxine. He stumbled in subsequent thyroid research and abandoned that line of research. He moved on to research involving the adrenal gland.

In 1929, Hungarian scientist Albert Szent-Györgyi, MD, PhD, temporarily joined the Mayo Clinic staff after having isolated hexuronic acid from cow adrenal glands; he wanted to obtain large quantities of adrenal glands from meat-packing houses in the St. Paul area. At the same time, Joseph Pfiffner, PhD, joined the Mayo Clinic to visit Dr. Kendall, bringing along his “Swingle-Pfiffner extract,” an extract from the adrenal gland.

They treated a patient with Addison’s disease with the extract in a painful procedure that led to the man’s recovery in 36 hours. Then they treated 48 more patients before supplies ran out. Considering the pain of the treatment involved and the short supply, a better treatment was needed.

Dr. Szent-Györgyi left the Mayo Clinic after nine months, offering to continue to work with Dr. Kendall on hexuronic acid research. Dr. Kendall wasn’t interested. (Note: Dr. Szent-Györgyi won the Nobel Prize for his discovery of hexuronic acid, renamed ascorbic acid—vitamin C.)

Dr. Kendall, who inherited Szent-Györgyi’s clinical setup for adrenal extraction, resolved to find “cortin.” His first problem was how to obtain enough adrenal glands. He came up with a clever business move, telling drug developer Parke-Davis that he would extract epinephrine from adrenal glands for the company if he got to keep the glands for his cortin work. From 1934–39, Dr. Kendall processed 150 tons of adrenal glands to make epinephrine, worth $9 million at the time.

In 1931, Dr. Kendall announced he’d found his compound, but later had to announce he was wrong. In 1933, the same thing happened. The Mayo Clinic Board of Governors decided another scientist in the lab should be in charge of purifying and characterizing cortin.

By 1936, Dr. Matteson said, the race to find the compound was heating up. Dr. Kendall had identified six separate compounds named A through F. Princeton and Columbia researchers had identified five each, and Swiss scientist Tadeusz Reichstein, PhD, had identified seven substances.

The effort to find cortin really ramped up in 1939, with the U.S. on the brink of war with Germany. Rumors were that cortin could allow military pilots to fly up to 40,000 feet without oxygen, and the U.S. National Research Council made isolating cortin the top priority, even ahead of developing penicillin. A committee of chemists, including Dr. Kendall, led the research, but failed.

Eventually, the Research Council’s funding stopped, but work continued. Dr. Kendall’s compound E became the most promising candidate. But he was nearly beaten: Dr. Reichstein figured out it was theoretically possible to make compound E out of compound A. He was the first to synthesize A, despite being hobbled by having just a small lab in a small country, without enough cow glands available.

Eventually, Lewis Sarett, PhD, who had been working for Merck on a cortin consortium, joined Dr. Kendall at the Mayo Clinic to speed up the pursuit. Dr. Sarett finally succeeded in synthesizing cortin in 1944 using oxen bile. It took 38 steps—the most complex synthesis performed up to that time.

Now, a new problem arose: Addison’s disease was rare, and the military’s interest had waned. Cortin was “a treatment in search of a disease,” Dr. Matteson said.

When Philip Hench, MD, joined the Mayo Clinic, he brought with him a crucial observation: He’d once seen a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) go into remission during a jaundice attack. Dr. Hench reasoned the body must produce an anti-inflammatory chemical, likely broken down by the liver. He called it Factor X and began a search for it.

Later, he and Dr. Kendall talked. They suspected Factor X might be compound E and resolved, “If we ever get enough substance E, let’s test it on RA.”

The 1st Patient

In 1948, “Mrs. G” came to the Mayo Clinic with severe RA, determined not to leave until she was cured. Drs. Kendall and Hench finally procured a supply of compound E from Merck, and they treated Mrs. G in September of that year (but not before dropping the glass vial with 5 grams of the substance on a marble floor—it somehow didn’t break).

They were stunned by the results. Mrs. G seemed transformed, going out shopping within days of the treatment when before she had barely been able to get out of bed. They gave the substance to other renowned rheumatologists to try in their clinics. These physicians found it worked for their patients, too.

The assessment of one Mayo Clinic physician? “It was like God had touched them.”

Although the drug produced wondrous results, Mrs. G’s case also became a lesson in the drug’s troubles. Her joints improved by at least “50%” a few days after the initial treatment, according to notes. But the dose was eventually reduced, and she suffered increasing musculoskeletal discomfort. Later, she became anemic and needed blood transfusions.

The relationship between Mrs. G and her doctors deteriorated. Later, in a letter, she referred to the “cruel things” done to her at the Mayo Clinic.

She died in 1954. The cause was unknown, but she had pulmonary edema, and Dr. Matteson said it’s possible she had a massive gastric hemorrhage from a probable ulcer.

Although use of the drug in Mrs. G’s case was done according to the best practices of the time, the case has left a long legacy, Dr. Matteson said.

“Lessons from this experience and other early clinical trials have led to better understanding of patient expectations,” he said, “and, in a positive way, helped to develop tools to address patient and investigator concerns, and foster patient and investigator protection in the conduct of clinical trials.”

Acknowledgment: Dr. Matteson noted the help of his colleague Thom Rooke, MD, a vascular medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic and author of The Quest for Cortisone, in preparing the lecture.

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.