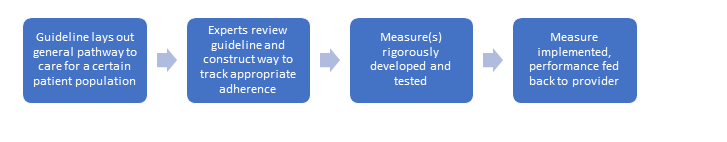

Because these guidelines are aimed at producing quality outcomes, they are a natural basis for outcome measures. A workgroup of experts analyzes guidelines and pinpoints specific measurable processes and outcomes. Once they have developed the appropriate measure to track adherence to guidelines, the measure can be implemented to give providers feedback on their care. Figure 1 is an example of this process.

Figure 1.

Quality measures can begin to fulfill their purpose only after they are implemented in a way that provides performance feedback to the provider. Tracking performance over time allows clinicians to see progress toward a more significant impact on the individual and society, even if they are simply tracking whether a certain process or action was completed.

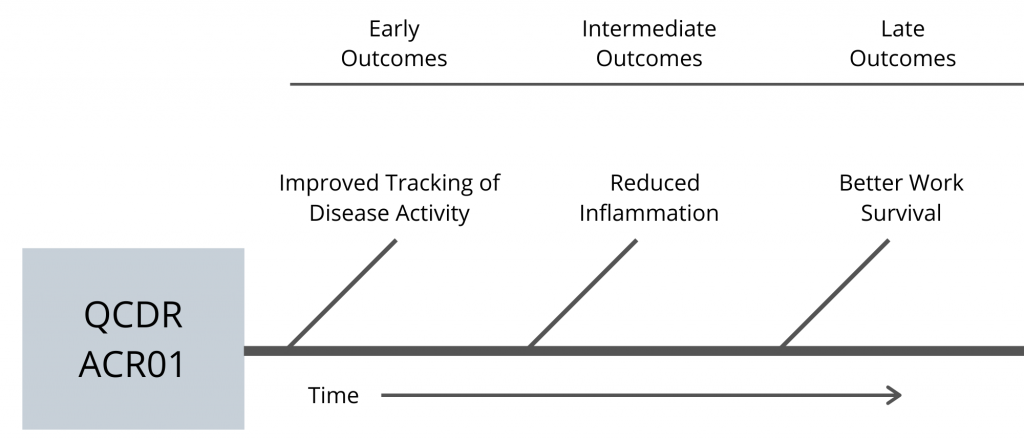

For example, one quality measure developed by the ACR, ACR01/QI 177, tracks whether providers are assessing disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients during at least half of their visits. Not only is this identified as an important process of care when treating RA patients, it also increases the likelihood of beneficial short- to long-term outcomes, such as reduced inflammation and the ability to continue working, occurring (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quality measures help give individual datapoints collected during clinical care more meaning and context by tracking over time. They illustrate that the choices clinicians make now can have long-lasting impacts on patients and society.

Structural Challenges

Measuring quality has several challenges, which have shaped MIPS since its inception in 2015. Although great strides have been made, complex structural roadblocks remain.

One pervasive problem is a lack of disease diversity. Measurements rely upon collecting enough data to create benchmarks that can be used to evaluate performance. How are measurements and benchmarks created for diseases with small amounts of data? Short answer: They aren’t. “That’s one of the reasons why RA and gout are common measures,” Dr. Suter explains. “They are some of the most common diagnoses. With less prevalent diseases, it’s hard to get to a number that represents good care or bad care, or better care or worse care, because you don’t have enough data.”

Another problem is due to the complexity of start and stop times for rheumatic diseases. Tracking start time for a disease like RA can be more complicated than knowing when a patient experiencing cardiac arrest begins receiving treatment, for example. Although it is possible to track the start of a new patient’s diagnosis, the percentage of RA cases diagnosed annually is insignificant compared with those already diagnosed.1