Beginning in 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will allow reporting through Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways (MVP). According to the CMS, this new participation framework seeks “to move from siloed activities and measures and toward an aligned set of measure options more relevant to a clinician’s scope of practice that is meaningful to patient care.”

Goals of the Quality Payment Program (QPP) are to increase quality of care and improve patient outcomes. According to the CMS, quality measures are useful tools for quantifying processes, outcomes and/or systems that improve the ability to provide effective, safe, efficient, patient-centered, equitable and timely care. Although quality measures are already an integral facet of measuring value and patient outcomes, they haven’t reached their full potential. MVPs still face challenges endemic to quality measurement, such as crafting measures and collecting feedback.

Siloed Data

Lisa Suter, MD, associate professor of medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., is a leading expert in rheumatology performance measurement and serves as a co-chair of the ACR’s Quality Measures Subcommittee. She has led, directed or consulted on the development of 33 hospital-level outcome measures, three clinician-level outcome measures and 11 clinician-level process measures; 25 are in current or planned use in federal payment programs.

The current difficulty, Dr. Suter believes, is that there are simultaneously too much and too little data. Providers collect large amounts of data during patient visits—health history, vital signs, new prescriptions and more—but those data are not always given context and purpose. “What we have right now is a lot of isolated data,” she says. “There is an overwhelming flood of information that’s not getting harnessed for advanced care. We don’t use it or leverage it.”

Measuring for quality aims to bridge that gap by tracking data and leveraging it for a better understanding of how to deliver comprehensive quality care. Quality measures capture and turn data into easily understood statistics, making it easier for previously siloed physicians to share information that increases the quality of care.

Creating Measures & Seeing Outcomes

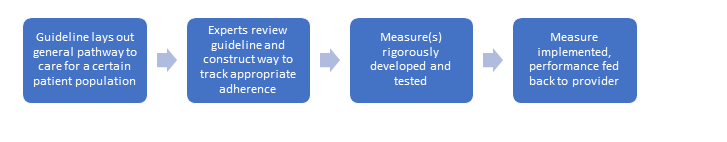

Quality measures are created using the latest research with important treatment implications; many are based on clinical practice guidelines. Evidence-based guidelines are developed to reduce inappropriate care, minimize geographic variation in practice patterns and enable effective use of healthcare resources. Adherence to practice guidelines is voluntary and cannot guarantee any specific outcome, but they are intended to provide guidance for patterns of practice.

Because these guidelines are aimed at producing quality outcomes, they are a natural basis for outcome measures. A workgroup of experts analyzes guidelines and pinpoints specific measurable processes and outcomes. Once they have developed the appropriate measure to track adherence to guidelines, the measure can be implemented to give providers feedback on their care. Figure 1 is an example of this process.

Figure 1.

Quality measures can begin to fulfill their purpose only after they are implemented in a way that provides performance feedback to the provider. Tracking performance over time allows clinicians to see progress toward a more significant impact on the individual and society, even if they are simply tracking whether a certain process or action was completed.

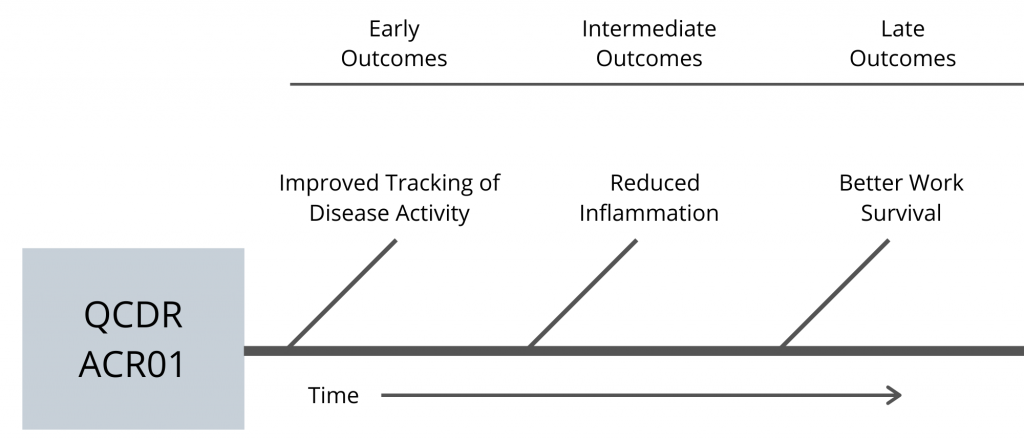

For example, one quality measure developed by the ACR, ACR01/QI 177, tracks whether providers are assessing disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients during at least half of their visits. Not only is this identified as an important process of care when treating RA patients, it also increases the likelihood of beneficial short- to long-term outcomes, such as reduced inflammation and the ability to continue working, occurring (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quality measures help give individual datapoints collected during clinical care more meaning and context by tracking over time. They illustrate that the choices clinicians make now can have long-lasting impacts on patients and society.

Structural Challenges

Measuring quality has several challenges, which have shaped MIPS since its inception in 2015. Although great strides have been made, complex structural roadblocks remain.

One pervasive problem is a lack of disease diversity. Measurements rely upon collecting enough data to create benchmarks that can be used to evaluate performance. How are measurements and benchmarks created for diseases with small amounts of data? Short answer: They aren’t. “That’s one of the reasons why RA and gout are common measures,” Dr. Suter explains. “They are some of the most common diagnoses. With less prevalent diseases, it’s hard to get to a number that represents good care or bad care, or better care or worse care, because you don’t have enough data.”

Another problem is due to the complexity of start and stop times for rheumatic diseases. Tracking start time for a disease like RA can be more complicated than knowing when a patient experiencing cardiac arrest begins receiving treatment, for example. Although it is possible to track the start of a new patient’s diagnosis, the percentage of RA cases diagnosed annually is insignificant compared with those already diagnosed.1

Overcoming Challenges

Although measuring quality will never be without flaws, Dr. Suter and her colleagues have worked diligently to solve challenges. In the past five years, measure developers have addressed two seemingly impossible tasks: clinic demographic differences and trade-offs.

Measuring performance must account for the variable demographics of different clinics and their patients. How can a medical practice with 50 newly diagnosed RA patients be compared with a practice that has 75 RA patients with 30 years of disease activity? The answer is risk adjustment.

“Risk adjustment evens the playing field.” Dr. Suter explains. “Statistical prediction models tell us, ‘this practice has x amount of older patients who have had the disease a long time, and y number of younger patients who are recently diagnosed. [Therefore] we can expect [the practice] to have measurement results in this range.’” Adjusting for the risks associated with certain group characteristics allows for the comparison of different practices. “That’s where quality comes in,” Dr. Suter continues. “We try to correct for the things that aren’t under the control of the clinician, so what’s left over is due to the quality of the care they provide.”

Finally, developers face inevitable trade-offs in creating measures, particularly in achieving a balance between how much information is collected and how much effort is required to collect it. The more data collected through measures, the better they can be refined for practical use. Yet the more data required for measurement, the less time clinicians may have to spend giving quality care.

“Useful measures find a balance that is acceptable—that minimizes burden but maximizes information for the clinician,” Dr. Suter explains. Although there will never be a measure without any flaws, by receiving input and asking their colleagues to share insight into measures, developers refine measures annually to propel the movement for value-based care forward.

“We must understand what works for clinicians. Please let us know what works, what doesn’t. How could we make measures better? What measures do you want to see?” Dr. Suter asks. “Clinicians should engage with the ACR to help us build better measures so we can do a better job.”

Valuing Value

Measuring quality through such frameworks as the MVPs is the future of federal reporting. You can take several steps to help the system work more smoothly.

Track your performance.“Dashboards give some context. Are we better than average for the nation? Are we worse than the average? They allow a practice to improve as a whole and can help that practice understand how they are doing relative to the national average.”

Engage with the ACR and other organizations that develop measures. Input from those on the front lines leads to measures that better match reality and track quality care. If you would like to volunteer your time with the ACR, click here. To learn more about the RISE registry, email the RISE team.

Finally, Dr. Suter challenges, “It takes courage to be measured, but it’s worthwhile. A lot of us have been out of school for a long time; we don’t get graded, and we don’t take tests that often. But measures are a mirror that allows us to reflect on our own care. I’m asking people to have an open mind about them.”

Allison Plitman, MPA, is the communications specialist for the ACR’s RISE Registry.

Reference

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, et al. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising? Results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 June;62(6):1576–1582.