Racial and ethnic quotas are fast becoming distant memories, but for the first half of the 20th century, they represented significant barriers to career development and advancement. During and after World War I, the American Jewry became the target of anti-Semitism from a variety of social groups, including the Ku Klux Klan and various immigration restriction advocates.

Ivy League universities were no exception, and several of these schools moved to restrict Jewish enrollment during the 1920s. Nativism and intolerance peaked in 1922 when the number of Jewish students at Harvard tripled to 21% of the freshman class (up from 7% in 1900). Harvard’s president, A. Lawrence Lowell, proposed a quota on Jewish enrollment, convinced that the university could only survive if the majority of its students came from old American stock. He proposed a 15% maximum number, reasoning that this would actually prevent future anti-Semitism. His suggestion was followed by most Ivy League universities as well as many others throughout the nation.1

Although 3,000 miles away, the University of Southern California (USC) School of Medicine in Los Angeles was no exception. Founded in 1885, it closed in 1920 due to lack of a sufficient endowment. The school resumed operations in 1928 and graduated its first class in 1932, concurrent with the opening of Los Angeles County General Hospital, which, for several years, was the largest hospital in the United States and had over 3,000 beds. Other than a small Seventh Day Adventist medical school known as College of Medical Evangelists (later Loma Linda), USC was the only medical school in Southern California, because the University of California (UC) Los Angeles, UC San Diego, UC Irvine, and UC Riverside were not built until the 1950s and 1960s. From 1931 until his sudden death weeks before Pearl Harbor, Paul S. McKibben, PhD, was the dean of the USC School of Medicine. He restricted the 54-member class to three members of the Jewish faith and one woman.

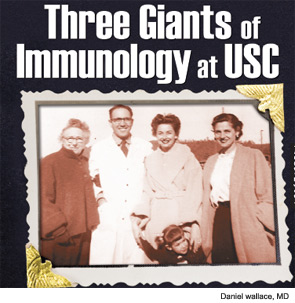

Companionship Born of Adversity

The Jewish classmates enrolled in the freshman class of 1940 included Samuel Rapaport, MD (1921–2011), Benjamin Simkin, MD (1920–2003), and my father, Leon Wallace, MD (1920–2009). They were exposed to institutional hazing by classmates, pranks, and insults that were condoned by the administration. As a consequence, the trio of Rapaport, Simkin, and Wallace became very close while carpooling and eating together so that wartime gas and food rations could be stretched.

Leon Wallace went on to Chicago and New York, where his published work in pulmonary hypertension in the late 1940s and early 1950s made a mark on the nascent field. After serving in the Korean War, my dad returned to Los Angeles, where he practiced cardiology and partnered with Ben Simkin at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center for 50 years. Sam Rapaport joined a no-longer-hostile USC (the Jewish quota was dropped after McKibben’s passing) and, after serving in the Air Force in 1950, became a renowned hematologist and with Don Feinstein published seminal studies on coagulation and coined the term “lupus anticoagulant.” His hematology textbook, Introduction to Hematology, was one of the few that actually read like a story. His additional discoveries included the development of the activated partial thromboplastin time, the importance of a trace of thrombin to activate factor V and VII—a description of the prothrombin activator complex—and the discovery that hemophilia A does not stem from a single genotype. He moved to UC San Diego Medical School in 1974, where he worked until his retirement in 1996. The family relationship continued when I had the privilege of working with his son, Mark, when he became chairman of the department of psychiatry at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Learning from Giants

When I came to USC as a freshman medical student in 1970 and attended lectures in McKibben Hall, my father, who had not seen Rapaport in several years, insisted that I look him up. Sam greeted me as if I were one of his sons. He was thin, wiry, soft spoken, and brilliant; I was in awe in his presence. I was introduced to the “immunology” group at USC, which included Edmund Dubois, MD, and the chief of rheumatology, George Friou, MD, who wrote the first paper on antinuclear antibody. The divisions of hematology and rheumatology shared an inpatient unit that took up the entire 14th floor of the county hospital, which enabled comingling in what was probably one of the best autoimmune units in the United States.

Ed Dubois (1923–1985) graduated from Johns Hopkins Medical School and, after serving in the Army during World War II, did a medical residency under Maxwell Wintrobe, MD, PhD, (author of the hematology textbook Clinical Hematology) in Utah, and at Parkland Hospital in Dallas under Tinsley Harrison, MD, (editor of Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine). He came to Los Angeles to do a year of pathology in 1948 at USC and stayed because he married Nancy Kully, whose father was the principal physician for MGM studios.

After getting one too many middle-of-the-night calls from Judy Garland asking for sleeping medication, Dubois met with Paul Starr, MD, who was the chairman of the department of medicine at USC, to volunteer his time. In 1950, Starr asked Dubois to start a clinic to follow up on eight patients who were positive for a new test known as the LE cell prep. Within ten years, Dubois had the largest lupus practice in the world and, when I first met him in 1970, followed 500 patients at LA County and had already published 200 papers, including the first edition of his lupus monograph, Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus.

Concurrent with his work at the county hospital, Dubois had a private practice in Beverly Hills. In the early 1950s, he practiced internal medicine and cardiology in partnership with Myron Prinzmetal, MD, (of Prinzmetal’s angina) and Eliot Corday, MD, (co-inventor of the ambulatory heart monitor with Norman Holter, and, whom, to his chagrin, never attained eponymous distinction).

I joined Ed’s practice once I completed my rheumatology fellowship in 1979. Dubois woke up at 5 a.m. and wrote for two hours every morning while vigorously fighting multiple myeloma, with which he survived an unusual seven years. He had two passions: photography and yachting. Ed was a friend of Ansel Adams and went on trips with him. While dying, he bought a boat and named it “Dubious,” and insisted on sailing every week until the end. His contributions included the first detailed descriptions of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, antimalarial retinotoxicity, avascular necrosis, drug-induced lupus, gangrene from vasculitis, a steroid protocol for managing central nervous system lupus, use of quinacrine for cutaneous disease, use of cyclophosphamide, as well as establishing the first NZB/NZW lab in the United States and the first report on HLA typing in lupus.

After graduating from Yale Medical School, George Friou (1919–1999) served in the Navy. In the 1950s and 1960s, he showed that a substance in the serum of patients with SLE reacted with the nuclei of cells; that substance was gamma globulin and the target in the nucleus was DNA complexed with histones. This led to him designing the first fluorescent antinuclear antibody test in 1957. Friou came to USC in the late 1960s and stayed until he moved to UC Irvine in 1980. He left the division in the extremely capable hands of Frank Quismorio, MD, and Rodanthi Kitridou, MD, while David Horwitz, MD, took his place as division chairman. Quiet but stern, Friou never felt comfortable on the West Coast. He spent every summer on an island off the coast of Maine that was accessible only by boat, and retired there in 1990. Unfortunately, he developed Alzheimer’s shortly thereafter.

I was truly blessed to experience the influences of these great men when I was a medical student, and this exposure played a major role in my decision to go into rheumatology. It is ironic that the nidus of this story originated from the friendship of three medical students who found strength and determination in the face of discrimination and prejudice.

Dr. Wallace is associate director of the rheumatology fellowship program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and clinical professor of medicine at David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.