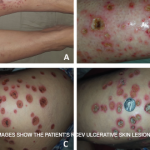

Petechia/purpura on the low limb due to medication induced vasculitis.

James Heilman, MD/wikipedia.com

WASHINGTON, D.C.—The vast majority of the attention given to vasculitis at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, year after year, focuses on ANCA-associated vasculitis and large-vessel vasculitis, said Philip Seo, MD, MHS, director of the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and moderator of the 2016 ACR Review Course titled, Neglected Vasculitis. That leaves out a lot.

“These are important diagnoses,” Dr. Seo said. “There have been a lot of advances made over the last several years. But does that mean there are lot of forms of vasculitis out there that you are going to run into on a regular basis that don’t get any love from the ACR? It’s hard to have an opinion about diagnoses that you don’t see on a daily basis.”

Dr. Seo described some of the ins and outs of three vasculitis forms that are less common: IgA vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schönlein purpura), polyarteritis nodosa and urticarial vasculitis.

IgA Vasculitis

The formal classification criteria for IgA vasculitis require the presence of purpura or petechiae unrelated to thrombocytopenia, predominantly in the lower limbs, with at least one of the following additional manifestations: arthritis or arthralgias, renal involvement, abdominal pain or evidence of IgA predominance on histopathology.

Dr. Seo cautioned that IgA vasculitis and IgA nephropathy are not necessarily the same thing, even though they come with roughly the same risk of renal failure. That “could be right, I’m just not sure,” he added. “I’m willing to say that these diagnoses are similar.”

Both IgA vasculitis and IgA nephropathy can be secondary to other disorders, which is “really important to keep in mind” because sometimes the primary diagnosis is treatable, he added. IgA nephropathy can be secondary to alcoholic cirrhosis, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease and chronic infection, among other things. By contrast, IgA vasculitis can be secondary to infection or the use of certain drugs, such as ciprofloxacin, aspirin, vancomycin or even cocaine.

Treatment options: Patients with IgA vasculitis presenting with colitis can be offered short courses of steroids. For patients with glomerulonephritis, the data don’t show any lasting benefit from cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine or cyclosporine. There may be a short-term benefit from steroids, but they probably won’t change long-term outcomes, Dr. Seo said. Rituximab is an option, but Dr. Seo said he hasn’t seen very impressive results. For purpura, dapsone is the top option, but not all patients will need the full 100 mg dose, he emphasized.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (cPAN) is a form of polyarteritis nodosa that is limited to the skin. Patients can present with livedo racemosa, a violet-toned, net-like pattern on the skin, when more superficial vessels are affected. Cutaneous nodules can present when deeper vessels are more affected.

Because the medium vessels are barely within the reach of a punch biopsy, Dr. Seo noted that a full-excision biopsy would be necessary in many cases to establish a diagnosis. He showed photos of two patients that he said could very well be taken for cPAN, but neither one was.

“No matter how convinced you are of morphology, I can’t overestimate the value of a good biopsy when it comes to making these diagnoses,” he said.

The “slam dunk” finding on biopsy for this diagnosis is true evidence of blood vessel inflammation, but many other signs, including diffuse inflammation and occlusion of a vessel leading to neutrophilic activity, can be interpreted by a dermatopathologist as being consistent with vasculitis, even when other diagnoses should be entertained, he noted.

“Biopsy reports can be really hard to interpret, and I really suggest you not only read the headline, but you actually read the description of exactly what it is the pathologist saw before you agree with that diagnosis of vasculitis,” Dr. Seo said.

Treatment: Dapsone, azathioprine and, in severe cases, infliximab or cyclophosphamide, can play a role in treatment. Rest, elevation and compression stockings can help as well. Dr. Seo also emphasized the need for gentle debridement, because being too aggressive can cause the lesions to grow.

Urticarial Vasculitis

Urticarial vasculitis involves dermatalogic wheals that last longer than a day, with evidence of vasculitis on biopsy. Chronic urticaria can be differentiated from urticarial vasculitis by the absence of bruising or arthralgias, which are not commonly associated with this diagnosis.

Urticarial vasculitis comes in two forms: normocomplentemic type, which might resolve with dapsone or colchicine and is less likely to involve systemic features; and the hypocomplementemic type, which can be secondary to lupus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome and malignancies. Those patients with anti-C1Q antibodies are at a higher risk for hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis.

Treatment: The normocomplementemic type doesn’t generally require chronic therapy, although ongoing immunosuppression is sometimes needed, Dr. Seo said. Those with the hypocomplementemic type can be treated with azathioprine, sulfasalazine, rituximab or the IL-1 inhibitor canakinumab.

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.