Patients with rheumatic diseases are no strangers to pain. Because back pain is highly prevalent worldwide—and higher yet among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and fibromyalgia—rheumatologists may need to have a few tips and tricks for preventing and alleviating back pain on hand. A tailored exercise program that helps improve mobility, strength, and function can be beneficial for the rheumatic patient with back or neck pain. Rheumatologists and rheumatology health professionals can help these patients by offering tips on posture, general health, and functional activities, as well as referring them for physical therapy. Through a multidisciplinary approach, patients who have rheumatic disease and present with back or neck pain can find relief.

Prevalence

The average point prevalence of low back pain worldwide is about 12%, and it is highly recurrent after the first episode.1 It is also more common in those between 40 and 80 years of age, as well as in women.1 Additional research shows that low back pain incidence is highest in the third decade of life, and overall prevalence increases with age until between 60 and 65, then gradually declines.2 In the United States, approximately 27% of adults have low back pain and about 14% have neck pain.3

In practice, patients of all ages, genders, and ethnicities present with back pain. “Back pain occurs along the spectrum, the continuum of life, if you will,” says Jan K. Richardson, PT, PhD, OCS, professor emeritus at the School of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C., and chief medical officer at Priority Care Solutions, Inc., in Tampa, Fla. “It’s not uncommon for adolescents as they’re moving into their teens and having these very fast growth spurts to develop back pain. … Then there seems to be a lull and the next group is the working group, those who are employed. There’s a high prevalence of back pain in the second, third, and fourth decade of the working population, especially in the demographic group who either has very active and labor-types of jobs and those who are very sedate and do a large amount of sitting.”

You’d want to try a conservative course of pharmacology and nonpharmacology treatments, including physical therapy, and exhaust those possibilities and interventions before you refer [the patient] on to a surgeon.

—Jan K. Richardson, PT, PhD, OCS

Risk Factors

In addition to job type, risk factors for low back pain include low educational status, stress, anxiety, depression, job dissatisfaction, and low levels of social support in the workplace.2 Psychiatric disorders frequently appear in patients with nonspecific back pain.4

Certain populations of patients with rheumatic disease also are more prone to back pain. For example, spondyloarthritis is specifically associated with inflammatory back pain.5 In postmenopausal women, back pain is significantly associated with RA, and it can be predictive of vertebral fractures.6

In patients with RA, the use of ambulatory devices—walkers, crutches, and wheelchairs—can cause back pain because the devices change the patient’s body mechanics and posture, Dr. Richardson says. Fibromyalgia and AS are also likely to cause back pain, she adds.

Prevention

The increasingly sedentary nature of the U.S. workplace today is causing back pain. Sitting for long periods of time—such as for eight hours a day at a computer—puts a lot of pressure on the spine. The same is true of manual labor or any job that requires frequent bending. Effective ways to prevent back pain and maintain a healthy spine include focusing on posture, making time to change positions throughout the day, staying physically active, and maintaining a healthy weight.

“Keeping in tune with good posture and trying to maintain that posture as long as you can throughout the day” is good for general spine health and preventing pain, according to Sarah Schoenhals, DPT, PT, inpatient rehabilitation physical therapist at Carondelet St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tucson, Ariz. This means maintaining the three natural curves of the spine during everyday activities, such as picking something up from the floor or sitting at a desk. “This can be achieved through strengthening specific muscles and sometimes stretching other muscles,” she says. “When you’re sitting at your desk and you get in that ‘lazy’ position—rounded shoulders and slumped forward—you lose all those natural curves.”

In addition to maintaining good posture, another general rule is to avoid staying in one position for long periods of time, Dr. Schoenhals says. “If someone sits for eight hours, suggest they get up and walk around or go somewhere they can lie down to relieve the pressure from their low back sporadically throughout the day,” she added.

Being physically active and keeping weight down is another key to preventing back pain. “In general, folks who maintain a healthy lifestyle as far as physical activity tend to have better outcomes and are less likely to report low back pain,” says Adam Goode, PT, DPT, PhD, assistant professor of community and family medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. For his patients, Dr. Goode recommends regularly participating in an activity they enjoy, as opposed to making specific suggestions, because if the patient picks something they like doing, it helps ensure that they’ll do it.

Core strengthening exercises are another way to improve spine and back health. Many people think of the core muscles as movers and rotators; however, their main purpose is to stabilize and control the spine. To improve core strength without causing back pain, the trunk/spine should remain stable while engaging the abdominal muscles, then attempting to move the extremities while maintaining that control and stabilization, Dr. Schoenhals says.

Treatment

Generally speaking, a patient who presents with back pain should work on stabilization and strength. “Usually when we see patients in the clinic for a first episode of low back pain, we work with them on reducing pain, pain-free core stabilization exercise, stretching, and a return to activity, such as sport-related or general activity,” Dr. Goode says.

If someone sits for eight hours, suggest they get up and walk around or go somewhere they can lie down to relieve the pressure from their low back sporadically throughout the day.

—Sarah Schoenhals, DPT, PT

Exercise therapy is a common method for treating back pain, although research has shown that aquatic therapy can be more effective for reducing disability and improving quality of life compared with land-based therapy.7 “People find a lot of relief from being in the pool,” Dr. Schoenhals says. “It relieves your joints and the buoyancy of the water takes off the pressure of your body weight.”

For recurring pain, finding out what the patient has done in the past to relieve symptoms is a good starting point. “Then the issue becomes, Are they continuing to perform those exercises even after the low back pain is gone?” Dr. Goode says. “We educate them to work on core stabilization and strength even after the episode because it can help prevent the next occurrence.”

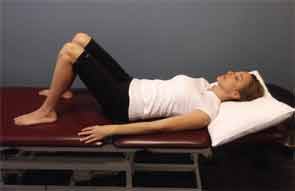

The lower back is the most common location of back pain, Dr. Schoenhals says, and posture is key for alleviating that pain and preventing recurrence, especially during functional movement. This becomes useful and important to remember during common activities at home, Dr. Schoenhals notes (see Figures 1 and 2–3).

When a patient presents with back pain in addition to rheumatic disease, diagnosing the cause in terms of structural versus nonstructural is important. “Back pain has many different ways it can manifest,” Dr. Goode says. “It can be from a specific source, like a disk herniation or severe disk degeneration, things we know can cause low back pain.” Conversely, with nonspecific back pain, magnetic resonance imaging shows nothing and there’s no muscle strain or any other structural issue. This type of pain requires a bit more investigation to diagnose.

Research suggests that physicians may find pain drawings particularly useful in discovering nonorganic factors affecting back pain.8 “If you have a drawing of someone and they note pain located in their low back, moving into their elbow and going down their arm to their fingers, and they identify these unrelated anatomical areas where they’re sensing discomfort, then you might suspect there’s a strong psychosocial component involved with their pain,” Dr. Richardson explains.

In fact, research indicates that psychiatric therapy may reduce back pain.4 Behavioral interventions also have proven useful for patients with chronic low back pain.9

Ultimately, a collaborative approach is ideal for a patient with rheumatic disease and back pain. A physical therapist will take several factors into account in creating an exercise plan for a specific patient, including where the pain is, the underlying cause, and other disease processes that may be in effect.

“Patients with rheumatic conditions can have several other comorbidities that may limit their ability to participate in certain exercises, and therapists are trained to tailor their exercise programs,” Dr. Goode says. A therapist also will help the patient progress through the program over time, as one exercise may become less effective as the treatment regimen progresses.

For example, patients who have AS “tend to get into this flexed position, losing the natural curvature of the spine, creating a lot of back pain,” Dr. Schoenhals says. “So if you find out early on they have this condition, a physical therapist can identify the most significant mobilization and strength deficits, and work with that individual to get on a good exercise program to keep their spine health and mobilization appropriate for as long as they can.”

In patients with RA, the cervical spine can be affected. If the patient has no instability and they don’t need corrective surgery, as determined by X-ray, a physical therapist can work with the patient on pain management, Dr. Schoenhals says.

For chronic pain that is not managed or improved with physical therapy and other conservative treatment, surgery or injections may be warranted, Dr. Goode says.

Surgery should be undertaken as a last resort, Dr. Richardson cautions. This is because even the pain of a herniated disk can be improved through physical therapy and a tailored exercise program. “You’d want to try a conservative course of pharmacology and nonpharmacology treatments, including physical therapy, and exhaust those possibilities and interventions before you refer [the patient] on to a surgeon.”

Kimberly J. Retzlaff is a medical journalist based in Denver.

References

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2028-2037.

- Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:769-781.

- Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: Estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2724-2727.

- Coste J, Paolaggi JB, Spira A. Classification of nonspecific low back pain. I. Psychological involvement in low back pain: A clinical, descriptive approach. Spine. 1992;17:1028-1037.

- Weisman MH, Witter JP, Reveille JD. The prevalence of inflammatory back pain: Population-based estimates from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-10. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:369-373.

- Kuroda T, Shiraki M, Tanaka S, Shiraki Y, Narusawa KI, Nakamura T. The relationship between back pain and future vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women. Spine. 2009;34(18):1984-1989.

- Dundar U, Solak O, Yigit I, Evcik D, Kavuncu V. Clinical effectiveness of aquatic exercise to treat chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2009;34(14):1436-1440.

- Udén A, Åström M, Bergenudd H. Pain drawings in chronic back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13(4):389-392.

- van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JWS, et al. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane back review group. Spine. 2000;25(20):2688-2699.