ORLANDO—Interstitial lung disease (ILD)—our patients get it. We need to know about it, and often we need to treat it. But ILD is a large alphabet soup of radiographic patterns, and most of us didn’t complete training in pulmonology and radiology.

ORLANDO—Interstitial lung disease (ILD)—our patients get it. We need to know about it, and often we need to treat it. But ILD is a large alphabet soup of radiographic patterns, and most of us didn’t complete training in pulmonology and radiology.

At the 2022 ACR Education Exchange, April 28–May 1, a cardiothoracic radiologist shared high-yield tips for ordering and interpreting chest computed tomography (CT).

‘What Kind of CT?’

Adam Guttentag, MD, associate professor of clinical radiology and radiologic sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, began his talk with the basics of chest CT imaging. “The type of CT you order depends on what questions you want answered,” he said. “Before, the only way to get thin sections was to order a high-resolution CT [HRCT]. But at many hospitals now, standard CT chests are thin section and aren’t ‘low resolution,’ as the names suggest.”

For known or suspected ILD, HRCT is best. “Think of HRCT as the ILD scan. It’s a specific protocol for ILD that should be used for the initial evaluation of ILD to get the best sense and description of the disease,” Dr. Guttentag said.

HRCT often involves standard CT sequences, plus two additional sequences: expiratory images that assess for air trapping and prone images that help clear out the dependent lung bases and confirm disease is truly present.

“Images can appear abnormal in [posterior lung fields] if the patient isn’t taking a deep breath on the supine film,” Dr. Guttentag said. “When it comes to follow-up scans for people with known ILD, HRCT is not necessary as long as your radiologist uses thin sections on standard CT.”

What about intravenous (IV) contrast? Dr. Guttentag explained that IV contrast does not help diagnose ILD or find nodules. It’s most useful for measuring adenopathy in the mediastinum and hila, and separating pleural from pulmonary disease. It can also help us see large vessel vasculitis, but a CT angiogram protocol is preferred for that.

“Don’t ever order a CT chest with and without contrast unless you’ve spoken to radiology and there’s a good reason for it. It just doubles the radiation dose,” said Dr. Guttentag.

Interpretation

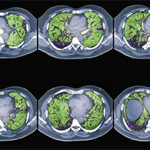

CT images may seem intimidating. But reviewing the images in addition to the radiologist’s report is better medicine. Dr. Guttentag broke down his approach into three steps: distribution, dominant pattern and clinical information.

First, assess the distribution of abnormalities. What area of the lung is involved? Are the abnormalities located at the top or bottom (i.e., apical or basilar)? Inner or outer (i.e., central or peripheral)?

Next, describe the dominant pattern of the abnormalities. Look for the following:

- Reticulation: too many fine lines;

- Groundglass: an increase in lung tissue density that doesn’t obscure the vessels;

- Consolidation: an increased density obscures the vessels and air bronchograms may be present;

- Nodules: too many dots;

- Honeycombing: small cystic black spaces touching each other, a sign of end-stage disease;

- Air trapping on expiratory images; and

- Traction bronchiectasis: dilated airways in areas of abnormal lung, another sign of fibrosis.

“Description and distribution may be diagnostic, obviating the need for lung biopsy,” Dr. Guttentag said. “They also help inform therapeutic intervention and prognosis. For example, a patient with honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis has established fibrosis that won’t respond to immunosuppressive therapy. But groundglass and consolidation could indicate active inflammation that’s potentially reversible.”

Most importantly, consider the clinical information. “Do the CT findings support your clinical diagnosis?” Dr. Guttentag asked. “The age and sex of the patient, acuity of symptoms and social and occupational history are all relevant here. And of course, is there clinical evidence of connective tissue disease [CTD]?”

‘Don’t ever order a CT chest with & without contrast unless you’ve spoken to radiology & there’s a good reason for it. It just doubles the radiation dose.’ —Dr. Guttentag

CTD ILD

Generally, CTD presents in the lungs as one of various patterns of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). Dr. Guttentag said, “Think of IIP as the way the lung is reacting to an insult. These are nonspecific histologic patterns of lung injury. The lung has limited ways of responding and trying to heal, and these insults may be autoimmune, inhalational, infectious, idiopathic or drug induced. The history, clinical exam and serologies are going to help put the pattern in the context of a clinical picture.”

ILD may precede clinical manifestations of CTD by months to years. “Up to 15% of cases of IIP will eventually be diagnosed with CTD, but IIP patterns aren’t specific to one CTD. There’s a lot of overlap,” Dr. Guttentag said.

“For example, many CTDs present with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). It’s ‘nonspecific.’ On the other hand, the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern is most commonly seen in patients with rheumatoid lung. Systemic lupus erythematosus tends to show up with pleural-pericardial disease or hemorrhage. And systemic sclerosis almost always manifests with NSIP. So if the pattern doesn’t fit with what you typically see in that disease, consider whether they have something else superimposed. History, lab data and communication with radiology are critical.”1,2

Classically, UIP appears as peripheral, basilar disease with honeycombing. In NSIP, groundglass opacities predominate, with the potential for sub-pleural sparing.3

Vasculitis & the Lungs

“Vasculitic diseases with pulmonary involvement have a highly variable presentation, but a lot depends on the size of the vessel involved,” Dr. Guttentag explained.

Example: Capillary involvement causes alveolar hemorrhage, and small artery involvement causes nodules, masses or consolidations in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis. In large vessel vasculitis, vessel stenosis and aneurysms are typical.4

Not All CTD Is Autoimmune

Dr. Guttentag took care to remind his audience that in patients with rheumatic disease and abnormal CT chest findings, we can’t forget about direct drug toxicity and opportunistic infections. “CTD itself isn’t always the culprit. Drug toxicity and infections may cause any IIP pattern, and clinical presentation may be acute or subacute,” he said.

Summary

Dr. Guttentag summarized take-home points in one slide. Many standard chest CTs are now thin section, so not all patients need a HRCT. But HRCT is essential for the initial evaluation of known or suspected ILD. Rheumatic diseases, drug toxicity and infection can have overlapping radiographic appearances because the lung can react to injury in only so many ways. Thus, keep your differential broad and integrate imaging findings with clinical history and laboratory data.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is an academic rheumatologist and an affiliate faculty member of the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. She received her training in internal medicine and rheumatology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She is also a member of the ACR Insurance Subcommittee.

References

- Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. High-Resolution CT of the Lung, 5th Edition. LWW; Fifth edition. 2014 Aug 19.

- Mira-Avendano I, Abril A, Burger CD, et al. Interstitial lung disease and other pulmonary manifestations in connective tissue diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Feb;94(2):309–325.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Sep 15;188(6):733–748.

- Chung MP, Yi CA, Lee HY, et al. Imaging of pulmonary vasculitis. Radiology. 2010 May;255(2):322–341.