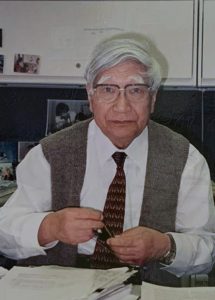

Japanese pediatrician Tomisaku Kawasaki, MD, who identified an inflammatory syndrome that affects children, died on June 5 in Tokyo. He was 95.

Tenacity & Attention to Detail

Born Feb. 7, 1925, in Tokyo, Dr. Kawasaki graduated from medical school at what is now Chiba University in Chiba, Japan, in 1948 and worked as staff pediatrician at the Red Cross Hospital in suburban Tokyo. It was there in 1961 that he saw his first patient with the disease that would eventually bear his name. Kawasaki disease has been in the news recently because some children testing positive for COVID-19 have exhibited comparable symptoms, including rash and extremely bloodshot eyes. “The connection between [the conditions] is a wide open question right now,” says pediatrician Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Kawasaki’s patient was a 4-year-old patient with unusual symptoms he could not diagnose. “The boy presented with a fever, congestion of the mucous membranes, cervical lymphadenopathy and desquamation,” says Philip Seo, MD, MHS, associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, director of both the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center and the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Fellowship Program, and physician editor of The Rheumatologist. “The patient eventually improved on his own and was discharged with the honest label of ‘diagnosis unknown.’”

Dr. Kawasaki subsequently had seven more patients with these unusual symptoms, which he documented in great detail and presented as a case series at a meeting of the Japanese Pediatric Association. When he submitted the series for publication, it was rejected; the reviewers suggested he had observed an atypical form of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

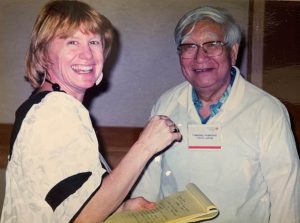

“There was almost an idea that because he was outside of the establishment, he could not possibly have described a new disease,” says Dr. Burns, who first met Dr. Kawasaki when she was a young infectious disease fellow and over the years came to consider him a dear friend.

During the next six years Dr. Kawasaki documented 50 similar cases of children with symptoms that included high fevers, extremely red eyes and lips, and a swollen red tongue, as well as swollen, peeling hands and feet. This case series was published.

“Maybe because he was unfettered by too much training, he could just see clearly what was in front of him,” says Dr. Burns. “Can you imagine today a rheumatologist waiting to report a new condition and gathering 50 patients over a period of years?”

With no subspecialty training in rheumatology, Dr. Kawasaki was an outlier whose work was not initially embraced by the strict, hierarchical academic pediatric establishment of 1960s’ Japan. But he was scrupulous in his pursuit of answers to this mysterious syndrome.

In each file he traced a little outline of a child and drew where the rash was on all 50 patients. He also included a handwritten timeline of symptoms—when the eyes got red, when the rash appeared, when the lips and tongue became red and swollen, as well as when all symptoms subsided and when the child smiled. “He even had biopsies of the skin from the fingertips,” Dr. Burns says. “Everything is there.”

Kawasaki disease was thought to be a self-limiting diagnosis with a benign course until Noboru Tanaka, the head of pathology at the hospital where Dr. Kawasaki worked, performed an autopsy on a child who had been diagnosed with Kawasaki disease.

“Dr. Tanaka’s autopsy demonstrated the child had died of a coronary artery thrombosis, establishing for the first time a connection between this mucocutaneous febrile illness and its pathomneumonic vascular finding,” says Dr. Seo.

It wasn’t until a decade later that clinicians began to accept that a hallmark of the disease was cardiovascular involvement. “I think it was a real psychological twist for [Dr. Kawasaki] to accept his disease could cause permanent harm and death in children,” says Dr. Burns, adding that the patients in his published paper all got better without any treatment.

In the ensuing years, there have been episodic outbreaks of Kawasaki disease in Japan and the U.S., and it became recognized as an independent syndrome, as well as the leading cause of acquired heart disease among children in these countries. The cause of these outbreaks is still unclear, although an investigation of environmental factors in the U.S. and Japan has indicated that a shift in wind direction, bringing with it possible pathogens, may induce the response in a particular host.

Generosity of Spirit

Dr. Kawasaki was not only renowned for his dedication and attention to detail as a physician, but also for his generosity of spirit. At the third International Kawasaki Disease Symposium in Tokyo in 1988, Dr. Kawasaki gave each speaker a small copper statue of a child cradling a lamb that he said symbolized caring for others. Thomas J. A. Lehman, MD, retired chief of pediatric rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York City, still has his and regards it with great fondness.

“Dr. Kawasaki was a kind, wonderful and generous person who was interested in the welfare of the children and felt he deserved no special credit for describing the syndrome,” says Dr. Lehman. “His only interest was in helping the affected children and those of us doing research with that goal.”

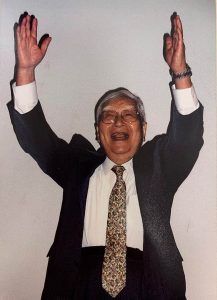

Described by colleagues as delightful, warm, engaging and approachable, Dr. Kawasaki has also been called a “rock star.” He had to have handlers at the International Kawasaki Disease Symposiums, because he was called upon to stop every few steps so young clinicians could take a selfie with him. Dr. Kawasaki was always happy to oblige, even when a trainee, so desperate to get a picture with him, followed him into the men’s room, according to rheumatologist Rae Yeung, MD, professor of pediatrics, immunology and medical science, and a senior scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

“He never tired of spending time with people, and he never got short with anyone,” Dr. Yeung says. “He was the most lovely, gentle man. Unassuming and yet incredibly knowledgeable and generous with his time—especially with young clinicians.”

Dr. Yeung says she met Dr. Kawasaki for the first time two decades ago and—despite his rock star status—when he would see her every three years at the symposiums, he always remembered her name.

After retiring from his pediatric practice in 1990, Dr. Kawasaki established the Japan Kawasaki Disease Research Center, which he led until last year. “He was a cheerleader for

the entire community working on Kawasaki disease,” Dr. Burns says.

Every three years Dr. Kawasaki and his wife, pediatrician Reiko Kawasaki, MD, attended the International Kawasaki Disease Symposiums together. According to Dr. Yeung, the couple would sit in the front row at each scientific session with blankets over their shoulders and feet and, even in their 90s, remain awake throughout.

“He was really an incredible guy,” Dr. Yeung says. “This is the pediatrician you wanted looking after your child. That’s how I’ll always remember him.”

Dr. Kawasaki was preceded in death by his wife. His survivors include two daughters and a son.

Renée Bacher is a freelance medical writer located Baton Rouge, La.

More about Dr. Kawasaki: Read the Japan Times story that first reported Dr. Kawasaki’s death. Also read this editorial by Physician Editor Phil Seo, MD, MHS, from June 2019: Thinking Big, Thinking Small.