2. Trimethoprim Sulfamethoxazole Prophylaxis

Abstract 1584: Mendel et al.3

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been commonly prescribed to patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis as chemoprophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii infection. However, this practice has become less common among patients treated with rituximab, which specifically depletes B cells (rather than the T cells that prevent Pneumocystis infection).

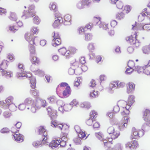

In a commercial claims and encounters database, the researchers in this retrospective study identified 919 patients with GPA who had been treated with rituximab; 31% of these patients had also received prescriptions for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Patients in this study were followed for a median of 496 days. The rate of serious infection was 6.1/100 person-years. The most common serious infections were pulmonary (36%) or sepsis (45%).

In multivariate analysis, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was negatively associated with serious infections (adjusted hazard ratio 0.5; 95% CI: 0.3–0.8) and outpatient infections (adjusted hazard ratio 0.7; 95% CI: 0.5–0.9). In this cohort, 13 infections with Pneumocystis jirovecii occurred, all in patients who had not received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Adverse events attributable to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole occurred at a rate of 29.6/100-person years while exposed to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and 13.4/100-person years when not exposed to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

These data indicate that patients with GPA treated with rituximab may benefit broadly from chemoprophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, beyond the prevention of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection. However, the calculus is not straightforward; for every serious infection avoided, two or three patients will likely experience an adverse event from trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. A full presentation of these interesting data may help clinicians decide on the appropriate use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in this setting.

3. Avacopan & DAH

Abstract 0684: Specks et al.4

The alternative pathway of complement plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of both GPA and MPA. Avacopan inhibits the alternative pathway of complement by binding the C5a receptor. The ADVOCATE trial randomized 331 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis to receive therapy with either avacopan (30 mg orally twice daily) or prednisone on a tapering schedule.5 At 26 weeks, the primary end point (defined as a Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score of 0) was achieved by equal proportions of patients in both arms (72.3% vs. 70.1%).

The ADVOCATE trial demonstrated that patients with severe forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis could achieve remission with minimal exposure to glucocorticoids. However, clinicians may hesitate to use avacopan in place of glucocorticoids for patients who present with the most severe manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis.

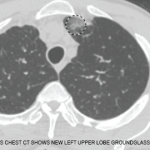

This study was a post-hoc analysis of the 12 patients in the ADVOCATE study who presented with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), most of whom had GPA (92%). Median glucocorticoid exposure during the first month following enrollment was considerably less among patients randomized to receive treatment with avacopan (625 mg vs. 1,627 mg). However, remission rates in both groups at 26 weeks were comparable (80% vs. 71.4%). No patients randomized to receive avacopan relapsed during the treatment period, and none of the patients in either group required mechanical ventilation.