The goal of “treating to a target” is not a new concept in clinical medicine. Indeed, in many specialties, goal-directed treating to target is already the standard. For example, the goal of reducing low-density lipoprotein is widely accepted and followed by cardiologists and primary care physicians (PCPs), as determined by the number of coronary artery disease risk factors present in each patient. The Joint National Commission (JNC) 7 blood pressure guidelines have also been widely adopted by the medical community. Physicians have come to accept that blood pressure must not exceed 140/90 mmHg in “normal” patients, and that blood pressures less than 130/80 mmHg must be targeted in patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Finally, endocrinologists and PCPs alike recognize the importance of achieving a hemoglobin A1C level as close to 6.0 mg/dl as possible, and use this value as an indicator of the success of their therapeutic strategy in achieving “tight” control of the patient’s diabetes in the outpatient setting.

At the same time, recent studies of patients with diabetes have shown that pushing for hemoglobin A1C levels less than 6.5 mg/dl in the elderly population may also lead to increased morbidity and mortality. The lesson from these studies is that “treating to target” is beneficial not just to avoid undertreating, but to avoid overtreating as well. It is difficult, however, to define the boundaries of overtreating and undertreating without first setting a target.

TABLE 1: Recommendations from the International Treat to Target Initiative

Overarching principles:

- The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis must be based on a shared decision between patient and rheumatologist.

- The primary goal of treating the patient with rheumatoid arthritis is to maximize long-term ,health-related quality of life through control of symptoms, prevention of structural damage, normalization of function and social participation.

- Abrogation of inflammation is the most important way to achieve these goals.

- Treatment to target by measuring disease activity and adjusting therapy accordingly optimizes outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis.

Ten recommendations on treating rheumatoid arthritis to target based on both evidence and expert opinion:

- The primary target for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis should be a state of clinical remission.

- Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity.

- While remission should be a clear target, based on available evidence low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative therapeutic goal, particularly in established long-standing disease.

- Until the desired treatment target is reached, drug therapy should be adjusted at least every 3 months.

- Measures of disease activity must be obtained and documented regularly, as frequently as monthly for patients with high/moderate disease activity or less frequently (such as every 3–6 months) for patients in sustained low disease activity or remission.

- The use of validated composite measures of disease activity, which include joint assessments, is needed in routine clinical practice to guide treatment decisions.

- Structural changes and functional impairment should be considered when making clinical decisions, in addition to assessing composite measures of disease activity.

- The desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease.

- The choice of the (composite) measure of disease activity and the level of the target value may be influenced by consideration of co-morbidities, patient factors, and drug-related risks.

- The patient has to be appropriately informed about the treatment target and the strategy planned to reach this target under the supervision of the rheumatologist.

Source: Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

Despite the use of a goal-directed approach in some inflammatory diseases (e.g., lowering serum uric acid to a target of 6.0 mg/dl in patients with gout), surprisingly, rheumatology as a specialty and rheumatologists in particular appear to be slow in adopting the regular use of standardized, objective metrics in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), let alone a goal-directed approach, linking an objective metric of disease activity to therapeutic intervention. The absence of a “target” does not mean that we have not recognized the need to lower disease activity. But what is the evidence that the philosophy of “the lower the better” holds true for RA disease activity?

Reviewing the Evidence

In 2008, an international expert panel comprised primarily of rheumatologists began review of available evidence on goal-directed therapy in RA. The results of this effort became the International Treat to Target Initiative, now endorsed by representatives and patients from over 46 countries, and published in 2010.1 This expert panel agreed on several “Overarching Principles” as well as specific recommendations (see Table 1).

Based on available evidence, the use of an outcome that includes an objective measure to guide therapy will ultimately facilitate patient care.2-4 For example, the Tight Control of Rheumatoid Arthritis (TICORA) study employed an arbitrary therapeutic algorithm that used no biologic agents and advanced therapy according to a structured algorithm every three months if patients did not achieve low disease activity as measured by the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28; i.e., DAS28≤3.2).2 Patients in the intensive therapy group achieved lower disease activity than did patients assigned to routine care.

The Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA) study used a computer algorithm to drive escalation of methotrexate therapy and showed that a greater percentage of patients achieved remission when they were treated according to this computer algorithm than when they were treated according to their physician’s intuition.3 The Behandel Strategieen (BeST) study compared four different therapeutic regimens, some of which included biologic therapies, others of which predominantly included traditional disease modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapies.4 The BeST study also showed that advancing patients every three months along a predefined therapeutic algorithm, if they were not in DAS low disease activity, led to better outcomes with less disease progression and better functional status more rapidly if patients were treated with either a biologic agent or traditional DMARDs.

The questions driven by these studies then become the following: 1) What is the best metric to use when measuring disease activity (e.g., DAS28, CDAI, SDAI)? and 2) What is the most appropriate (or realistic) target (e.g., remission or low disease activity)? To date, only a few small studies have attempted to compare the efficacy of different treatment targets in RA.5 Given the debate in the literature about the relative utility and ease of use of patient-reported and physician-reported outcomes, it is unlikely that this issue will be resolved definitively or that the rheumatology community will reach consensus regarding which objective metric is best to use in setting a patient’s target. Nevertheless, the “treat to target” concept remains essential: set a target, measure progress by a standardized metric, and adjust therapy accordingly.

Treat to Target in Practice

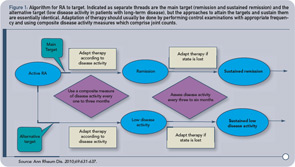

We suggest that in clinical practice, each rheumatologist should select a target that makes the most sense for an individual patient and initiate and then adjust therapeutic strategies in order to reach that target. Whether that outcome measure is a single variable (e.g., joint count) or a composite of multiple variables (e.g., DAS28), the use of an outcome measure is important so that a patient’s progress can be effectively evaluated. The algorithm proposed by the International Treat to Target Initiative for treating RA to target is presented in Figure 1.1

Since clinical trials generally focus on several primary endpoints (e.g., relief of signs and symptoms of disease, improvement in patient-reported outcomes, and inhibition of structural progression of disease), it would seem that an objective metric that is a composite outcome measure makes the most sense. As rheumatologists, however, we feel strongly that any composite measure needs to include an assessment of tender and swollen joints, since these are the principal “target organ” of rheumatoid arthritis. One thing seems clear from the available data, however: in the absence of an objective metric and a specific goal or target, it can be difficult to justify alteration in therapy, whether dose escalation of one medication, such as methotrexate, or addition of another, such as a biologic agent.

Given the importance of a target, we must first recognize our goal in treating RA to target. Is our goal to reduce pain in the present? To reduce disability in the future? To reduce associated cardiovascular mortality? All of the above?

Next, we must determine the frequency with which we evaluate patients for their achievement of target. Should we be monitoring patients every month? Every three months? We feel that the frequency of evaluation should ultimately depend upon the patient’s level of disease activity, with patients with higher disease activity requiring more frequent monitoring.

Finally, we must take into consideration the rate at which different patients achieve their targets, and decide how important is the speed with which they achieve their targets. Is reaching the target over a three-month period better than reaching it over a six- to nine-month period? Do we initiate therapy with a DMARD and then escalate with a second DMARD or biologic as needed, or do we initiate therapy with multiple agents at once and then reduce the dose of one or more agent as the disease comes under control?

Of course, patients must be partners in the decision to treat to target. The escalation of therapy with a biologic, for example, requires willingness on the patient’s behalf either to self-inject medication or to schedule an appointment at an infusion center for intravenous administration. Patients must also monitor themselves closely for any signs of infection, as the presence of infection is a limiting factor to the escalation of therapy.

Ultimately, we must remember that it is important to distinguish active disease from established damage when treating to target, given that active disease can be modified but damage cannot. Also, treating to target may have differential efficacy when employed as a treatment strategy in patients with early stage versus late stage disease. Indeed, while aiming for remission in all patients may seemingly make sense, aiming for this target in patients with late- or very late–stage disease may not be feasible. In these patients, we may have to recognize that “formal” remission may not be possible and low disease activity may be the best we are able to achieve.

Despite the challenges and potential limitations of this approach to therapy, we respectfully propose that it is time to refine our concept of “treating to target” in the care of patients with RA.

Despite the challenges and potential limitations of this approach to therapy, we respectfully propose that it is time to refine our concept of “treating to target” in the care of patients with RA. This is best accomplished by adopting and integrating the overarching principles and recommendations of the International Task force in our clinical practices.

Dr. Bernstein is a fellow in the division of rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery, in New York, N.Y. Dr. Gibofsky is professor of medicine and public health at Weill Medical College of Cornell University and attending rheumatologist at Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, N.Y. He is chair of the United States “Treat to Target” Committee and a member of the International Group.

References

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): A single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:263-269.

- Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ, et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: Aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial). Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1443-1449.

- Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study). Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:S126-S135.

- van Tuyl LH, Lems WF, Voskuyl AE. Tight control and intensified COBRA combination treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: 90% remission in a pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1574-1577.