EULAR 2022 (VIRTUAL)—Treat to target is a familiar phrase in rheumatology. Regardless of the disease, the clinical goals are the same: minimize and/or abolish symptoms, improve quality of life and improve level of function. So what is it about gout that makes treating to target so difficult?

EULAR 2022 (VIRTUAL)—Treat to target is a familiar phrase in rheumatology. Regardless of the disease, the clinical goals are the same: minimize and/or abolish symptoms, improve quality of life and improve level of function. So what is it about gout that makes treating to target so difficult?

At the 2022 Congress of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), Lisa Stamp, MB ChB, FRACP, PhD, DipMus, professor, Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand, shed light on treating to target in gout.

The Difference

Treating to target in gout differs from other rheumatic diseases. “In rheumatoid arthritis, for example, we target low disease activity (LDA) or remission, and assess this with a composite disease activity score,” Professor Stamp explained. “But in gout, we have no widely validated LDA or remission indices. Serum urate concentration has been accepted as the primary outcome measure in clinical trials of urate lowering therapy (ULT) because it allows for smaller, shorter and cheaper randomized controlled trials (RCTs).”

However, a serum urate target has proven problematic, and Professor Stamp proceeded to explain why.

The Controversy

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a Guideline on Management of Acute and Recurrent Gout, which advocated a treat-to-symptom rather than treat-to-target approach for gout management.1 The ACP determined that “evidence was insufficient to conclude whether the benefits of escalating ULT to reach a serum urate target outweigh the harms associated with repeated monitoring and medication escalation,” and “although there is an association between lower urate levels and fewer gout flares, the extent to which the use of ULT to achieve various targets can reduce gout flares is uncertain.”

Ultimately, the ACP recommended initiation of ULT only after careful consideration of the benefits, harms and cost. Evidence for monitoring serum urate levels was deemed insufficient and, thus, not recommended either.

“As you can imagine, this caused quite a large amount of consternation amongst the rheumatology community—specifically amongst those who have a real interest in gout management,” Professor Stamp said.

What’s the Issue?

Why is it so difficult to show that achieving target serum urate improves clinical outcomes in gout? Professor Stamp explained that it takes time for flares and tophi to resolve, and most randomized, controlled trials of ULT have been too short to show benefit. Further, there’s been no placebo arm in trials that could highlight the benefit of ULT due to ethical concerns. The paradoxical increase in flares upon starting ULT also complicates the picture.

To illustrate her point, Professor Stamp drew the audience’s attention to the 2005 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the effectiveness of febuxostat, compared with allopurinol, for which the primary end point was serum urate less than 6.0 mg per deciliter (mg/dL) at the last three monthly measurements.2 “Data clearly showed that flares reduced over time,” she said, “but even after 12 months, patients were still having flares.”

The Evidence

Professor Stamp et al. have worked tirelessly to find evidence to support a treat-to-target approach for gout. The key has been showing that serum urate is an adequate surrogate end point in clinical trials.

In 2018, they published a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 10 randomized, controlled trials and three open label extension studies.3 No association was found between the relative risk of gout flare and the difference in proportions of individuals with serum urate less than 6.0 mg/dL in the randomized, controlled trials that had a maximum trial duration of 24 months. However, “based on observational ecological study design data—including longer duration extension studies”—there was an association with reduced gout flares. Further, the duration of ULT was inversely associated with the proportion of patients experiencing flare.

“We decided the next way forward was to use individual patient-level data from two, two-year RCTs. We wanted studies that would be long enough to show a relationship,” Professor Stamp continued.

Stamp et al. published results from this work in Lancet Rheumatology this past January.4 They compared serum urate responders (i.e., patients with an average serum urate of less than 6.0 mg/dL between 6 and 12 months post-baseline) with serum urate non-responders (i.e., those with average serum urate greater than 6.0 mg/dL). From the combined individual data from both trials, “significantly fewer serum urate responders had a gout flare than did serum urate non-responders between 12 and 24 months (27% vs. 64%; adjusted odds ratio: 0.29 [95% confidence interval 0.17 to 0.51], P<0.0001).” The mean number of flares per patient per month between 12 and 24 months was significantly lower in the serum urate responder group as well.

To summarize, Professor Stamp said, “This study provides evidence that a treat-to-target serum urate approach leads to improved clinical outcomes for our patients.”

Gout experts hope these data will lead to an alignment of gout management recommendations between rheumatology organizations and the ACP in the future. Of note, this evidence was limited by the fact that it relied on post-hoc analysis. But gout experts remain hopeful it will be enough to prompt revision of ACP guidelines.5

Professor Stamp was careful to note that “we need to think about more than just serum urate in gout. … Journals are starting to push back against using serum urate as the primary outcome for clinical trials, and it’s really interesting to note that the first of these—where gout flares were the primary outcome—was only just published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2022.”6

We now have increasing evidence from a post-hoc analysis that a serum urate target less than 6.0 mg/dL results in improved clinical outcomes for people with gout.

What’s the Target?

We finally have data to support the use of serum urate as a surrogate outcome measure for gout flares, but what’s the most appropriate target level?

To date, no head-to-head trials have compared the current serum urate target of 6.0 mg/dL with lower or higher targets. However, a recent study by Dalbeth et al. examined intensive ULT in patients with erosive gout.7 Improvement was seen in those with serum urate less than 5 mg/dL as well as 3.4 mg/dL, with no between-group differences. “This data suggests that there is no benefit of a lower target,” Professor Stamp said.

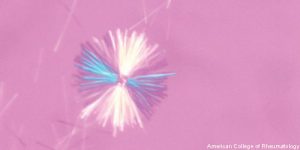

Rheumatologists also wonder if the serum urate target should change for patients over time. “For many patients, continuation of treatment in the absence of clinical signs or symptoms is challenging and can carry significant medication burden,” said Professor Stamp. “So an alternative strategy would be to induce MSU [monosodium urate] crystal dissolution with a lower target serum urate, and then maintain a state of MSU crystal dissolution with a higher target serum urate after that.”

This idea was proposed by Perez-Ruiz et al. in 2011—the so-called “dirty dish” hypothesis, whereby “more is required to get it clean than to keep it clean.”8 Further study is necessary in this regard.

In Sum

We now have increasing evidence from a post-hoc analysis that a serum urate target less than 6.0 mg/dL results in improved clinical outcomes for people with gout. The rheumatology community hopes these data will result in commensurate treat-to-target recommendations for gout management from other professional organizations. However, we still have work to do regarding which serum urate target results in the best clinical outcomes.

“If we cannot define a single target, why should we be treating to target serum urate at all?” Professor Stamp asked.

Samantha C. Shapiro, MD, is an academic rheumatologist and an affiliate faculty member of the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. She is also a member of the ACR Insurance Subcommittee.

References

- Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA, et al. Management of acute and recurrent gout: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 3;166(1):58–68.

- Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 8;353(23):245–2461.

- Stamp L, Morillon MB, Taylor WJ, et al. Serum urate as surrogate endpoint for flares in people with gout: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018 Oct;48(2):293–301.

- Stamp LK, Frampton C, Morillon MB, et al. Association between serum urate and flares in people with gout and evidence for surrogate status: A secondary analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Rheumatology. 2022 Jan;4(1):e53–e60.

- Bardin T, Richette P. Uricaemia as a surrogate endpoint in gout trials and the treat-to-target approach for gout management. Lancet Rheumatology. 2022 Jan;4(1):e7–e8.

- O’Dell JR, Brophy MT, Pillinger MH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of allopurinol and febuxostat in gout management. NEJM Evidence. 2022 Mar;1(3):10.1056/evidoa2100028.

- Dalbeth N, Doyle AJ, Billington K, et al. Intensive serum urate lowering with oral urate-lowering therapy for erosive gout: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Jun;74(6):1059–1069.

- Perez-Ruiz F, Herrero-Beites AM, Carmona L. A two-stage approach to the treatment of hyperuricemia in gout: The “dirty dish” hypothesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Dec;63(12):4002–4006.