Part 1 of a 2-part series. This article will cover the history of the fibromyalgia (FM) concept, current thinking on FM, and the epidemiology of the disease. Part 2 will appear in the November 2009 issue and will cover the role of pain processing in FM and potential treatment methods.

The Beginning of FM

Although there are clear descriptions of individuals with what we now call FM going back centuries in the medical literature, Sir William Gowers coined the term of “fibrositis,” which was considered a form of muscular rheumatism caused by inflammation of fibrous tissue overlying muscles.1 Although other terms such as “psychogenic rheumatism” were proposed and used in the mid-20th century, the term “fibrositis” remained the most widely used term to describe individuals with chronic widespread pain and no alternative explanation.

Several authors began to suggest that this term was a misnomer because there was no inflammation of the muscles. Moldofsky and colleagues performed seminal studies showing that individuals with fibrositis suffered from objective sleep disturbances, and showed that these same symptoms could be induced in healthy individuals deprived of sleep.2-5 Hudson and colleagues were arguably the first investigators to note the strong familial tendency to develop FM, and proposed that this condition is a variant of depression, coining the term “affective spectrum disorder.”6,7 In parallel during this period, Yunus and colleagues similarly began to note the high frequency of associated functional somatic syndromes, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and headache, with FM, again steering the focus away from skeletal muscle.8 Nonetheless, the theories positing a pathophysiologic role of skeletal muscle took time to fade, persisting into the mid-1990s.9-11

Just as spastic colitis became IBS, temporomandibular joint syndrome became temporomandibular disorder when it was recognized that the problem was not in the joint; chronic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) syndrome became chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) when it was realized that this syndrome occurs commonly after many viral illnesses and without infection with this pathogen; and fibrositis became FM.

It had also become clear that FM is not just FM. There is now significant evidence that FM is part of a much larger continuum that has been called many things, including functional somatic syndromes, medically unexplained symptoms, chronic multisymptom illnesses, somatoform disorders, and, perhaps most appropriately, central sensitivity syndromes (CSS). Yunus et al showed FM to be associated with tension-type headache, migraine, and IBS. Together with primary dysmenorrheal, these entities were depicted by Yunus in a Venn diagram in 1984, emphasizing the epidemiological and clinical overlap between the syndromes.8 In this article, the more recent term, CSS as proposed by Yunus, is used, because I feel that this represents the best nosological term at present for these syndromes.12 (See Table 1, above.)

TABLE 1: Clinical Syndromes Currently Considered Parts of the CSS Spectrum

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Irritable bowel syndrome and other functional gastrointestinal disorders

- Temporomandibular joint disorder

- Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements in sleep

- Idiopathic low back pain

- Multiple chemical sensitivity

- Primary dysmenorrhea

- Headache (tension > migraine, mixed)

- Migraine

- Interstitial cystitis/chronic prostatitis/painful bladder syndrome

- Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis

- Myofascial pain syndrome/regional soft tissue pain syndrome

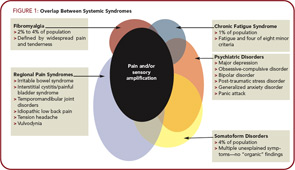

There is also a clear overlap between the CSS disorders and a variety of psychiatric disorders. This overlap likely occurs at least in part because the same neurotransmitters (albeit in different brain regions) are operative in psychiatric conditions. The presence of co-morbid psychiatric disturbances is somewhat more common in individuals with CSS seen in tertiary care settings than primary care settings.13,14 Figure 1 (below) demonstrates the overlap between FM, CFS, and a variety of regional pain syndromes, as well as psychiatric disorders,and shows that the common underlying pathophysiological mechanism seen in most individuals with FM, and large subsets of individuals with these other syndromes, is central nervous system (CNS) pain or sensory amplification.

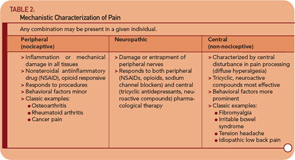

The use of research methods such as epidemiological and twin studies, experimental pain testing, functional imaging, and modern genetics has led to substantial advances in understanding several of these conditions, most notably FM, IBS, and temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJD). Together, these advances have led to an emerging recognition that chronic central pain itself is a “disease,” and that many of the underlying mechanisms operative in these heretofore “idiopathic” or “functional” pain syndromes may be similar, no matter whether the pain is present throughout the body (e.g., in FM), or localized to the low back, bowel, or bladder. Therefore, the more contemporary terms used to describe conditions such as FM, IBS, TMJD, vulvodynia, and related entities include “central,” “neuropathic,” or “non-nociceptive” pain.15,16 Furthermore, most investigators feel that the neurobiological underpinnings of these conditions undermine the psychiatric construct of “somatization,” at least with respect to the notion that these phenomena are the somatic representation of psychological distress, with no “real” pathological basis. Table 2 (p. 20) shows a suggested schema for classifying pain syndromes based on their underlying mechanism. It is important to recognize that even patients with “peripheral” pain syndromes such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis will often have elements of central pain that need to be treated as such, which is why the FM construct has moved well beyond simple relevance to functional somatic syndromes.

The current thinking about these overlapping symptoms and syndromes is as follows:

- The core symptoms seen in individuals with these illnesses are multifocal pain, fatigue, insomnia, cognitive or memory problems, and, in many cases, psychological distress.17,18 Some individuals in the population only have one of these symptoms, but more often individuals have many, and the precise location of the pain and the predominant symptom at any given point change over time. Thus, in clinical practice, it is useful to consider an FM-like or central pain syndrome when individuals have multifocal pain combined with other somatic symptoms.

- The presence and severity of these symptoms occur over a wide continuum in the population. All of our current diagnostic labels are at some level arbitrary because there is no objective tissue pathology or gold standard to which “disease” can be anchored.

- These symptoms and syndromes occur approximately 1.5 to two times more commonly in women than in men. The gender difference is often more apparent in clinical samples (especially tertiary care) than in population-based samples.13,14

- There is a strong familial predisposition to these symptoms and illnesses, and studies clearly show that these somatic symptoms and syndromes are separable from depression and other psychiatric disorders.19,20

- A variety of biological stressors seem to be capable of either triggering or exacerbating these symptoms and illnesses; these include physical trauma, infections, early life trauma, and deployment to war, in addition to some types of psychological stress (e.g., there was no increase in somatic symptoms or worsening of FM following the terrorist attacks of 9/11).21-24

- Groups of individuals with these conditions (e.g., FM, IBS, headache, TMJD, etc.) display diffuse hyperalgesia (increased pain in response to normally painful stimuli) and/or allodynia (pain in response to normally nonpainful stimuli). Many of these conditions have also been shown to demonstrate more sensitivity to many stimuli other than pain (i.e., auditory, visual) and data suggest that these individuals have a fundamental problem with pain or sensory processing rather than an abnormality confined to the specific body region where the pain is being experienced. In fact, the expanded relevance of the FM construct relates to the idea that all individuals (with and without pain) have different “volume control” settings on their pain and sensory processing. As such, their position on this bell-shaped curve of pain or sensory sensitivity largely determines whether they will have pain or other sensory symptoms over the course of their lifetime and how severe these symptoms will be.

- In addition to pain and sensory amplification, other shared underlying mechanisms that may be partly responsible for symptom expression have been identified in these illnesses, but will not be reviewed in detail here. These mechanisms include: 1) neurogenic inflammation, especially of mucosal surfaces, leading to increased mast cells and the appearance of a mild inflammatory process; 2) dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system; and 3) hypothalamic pituitary dysfunction.

- Similar types of therapies are efficacious for all of these conditions, including both pharmacological (e.g., tricyclic compounds such as amitriptyline) and nonpharmacological treatments (e.g., exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy). Conversely, individuals with these conditions typically do not respond to therapies that are effective when pain is due to damage or inflammation of tissues (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, opioids, injections, and surgical procedures).

Epidemiology and Clinical Studies

The large numbers of studies that have directly compared the rate of FM in other related CSSs, and vice-versa, or rates of co-morbidities between syndromes, will not be reviewed here because they have been covered elsewhere. Instead, I will focus on describing several lines of research that have better clarified the “big picture” with respect to the inter-relationships of these symptoms and syndromes.

Twin Studies

Kato and colleagues, using a large Swedish twin registry, have performed a series of studies first showing the comorbidities with chronic widespread pain, and then later examined a number of functional somatic syndromes and the relationship of these symptoms to those of depression and anxiety.18,25 These studies clearly demonstrated that functional somatic syndromes such as FM, CFS, IBS, and headache have latent traits (e.g., multifocal pain, fatigue, memory and sleep difficulties) that are different than (but overlap somewhat with) psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression. Interestingly, the findings are exactly those found in functional neuroimaging studies where, for example, individuals with FM alone primarily have increased activity in the regions of the brain that code for the sensory intensity of stimuli (e.g., the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, posterior insula, and thalamus), whereas the patients with FM with comorbid depression also have increased activation in brain regions coding for the affective processing of pain, such as the amygdale and anterior insula.26 The notion that there are two overlapping sets of traits, one being pain and sensory amplification, and the other being mood and affect, is also seen in other genetic studies of idiopathic pain syndromes.27 Twin studies have also been useful in teasing out potential underlying mechanisms versus “epiphenomena.” Buchwald and colleagues have compared identical twins with and without symptoms and have found that, in many cases, the two twins share abnormalities in sleep or immune function, yet have markedly different symptom profiles. These investigators have likewise suggested that this is evidence of a problem with perceptual amplification in the affected twins.28,29

It had also become clear that fibromyalgia is not just fibromyalgia. There is now significant evidence that fibromyalgia is part of a much larger continuum that has been called many things, including functional somatic syndromes, medically unexplained symptoms, chronic multisymptom illnesses, somatoform disorders, and, perhaps most appropriately, central sensitivity syndromes.

Environmental Stressors

As with most illnesses that may have a genetic underpinning, environmental factors may play a prominent role in triggering the development of FM and related conditions. Environmental stressors temporally associated with the development of either FM or CFS include early life trauma, physical trauma (especially involving the trunk), emotional stress, and certain infections such as Hepatitis C, EBV, parvovirus, and Lyme disease. The disorder is also associated with other regional pain conditions or autoimmune disorders.24,30,31 Of note, each of these stressors only leads to chronic widespread pain or FM in approximately 5% to 10% of individuals who are exposed; the overwhelming majority of individuals who experience these same infections or other stressful events regain their baseline state of health.

Wolfe’s “Symptom Inventory”

Although an early advocate of the FM construct, more recently, Wolfe has become critical of the construct, arguing that FM is not a discrete illness but rather the end of the continuum.32 A contrary opinion, which I share, is that FM is both a discrete illness (i.e., an individual with FM) and the end of a continuum of pain processing. Wolfe has performed seminal work showing that the degree of “FM-ness” an individual with any rheumatic disorder has (including individuals with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, regional pain syndromes, etc.) as measured by his Symptom Inventory is closely correlated with their level of pain and/or disability, even if they do have a “peripheral” cause for their pain.33 The Symptom Inventory (or other measures of the current or lifetime level of somatic symptoms or “somatization”) is a good measure for whether an individual has a CSS or an element of central sensitivity, regardless of whether or not they also have a peripheral cause for their pain. I predict that genetic factors, such as those discussed below, will be shown to be highly predictive of these measures, and that functional imaging (e.g., hyperactivity or increases in excitatory neurotransmitters in brain regions such as the insula that code for the intensity of all sensory information) and other research methods will similarly show that these self-reported measures have strong biological underpinnings.34-37

Genetic and Familial Predisposition

Evidence exists for a strong familial component to FM and all other CSSs. Arguably, this component has been best studied in twin studies comparing a variety of functional somatic syndromes, and in FM. Regarding the development of FM, Arnold and colleagues showed that the first-degree relatives of individuals with FM had an eight-fold greater risk of developing FM compared with those in the general population.20 Family members of individuals with FM are more sensitive to pressure stimulation (i.e., have a lower pain threshold) than family members of controls, irrespective of the presence of pain. Furthermore, family members of individuals with FM are also much more likely to have other pain syndromes, such as IBS, TMJD, headaches, and other regional pain syndromes.38,39 Similarly, strong genetic predisposition to chronic pain, and to nearly all of the CSSs, has similarly been noted. These observations are congruent with the twin studies that suggest that approximately 50% of the risk of developing one of these disorders is genetic, and 50% is environmental.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to read the November issue of The Rheumatologist for the second part of this series, which will address the role of pain processing in FM and potential treatment methods.

Dr. Clauw is professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

References

- Gowers WR. A lecture on lumbago: Its lessons and analogues. Br Med J. 1904; 1: 117-121.

- Bennett RM. Fibrositis: Misnomer for a common rheumatic disorder. West J Med. 1981;134:405-413.

- Simms RW. Fibromyalgia is not a muscle disorder. Am J Med Sci. 1998;315:346-350.

- Moldofsky H, Lue FA. The relationship of alpha and delta EEG frequencies to pain and mood in ‘fibrositis’ patients treated with chlorpromazine and L-tryptophan. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1980;50:71-80.

- Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P, England R, Smythe H. Musculosketal symptoms and non-REM sleep disturbance in patients with “fibrositis syndrome” and healthy subjects. Psychosomt Med. 1975;37:341-351.

- Hudson JI, Hudson MS, Pliner LF, Goldenberg DL, Pope HGJ. Fibromyalgia and major affective disorder: A controlled phenomenology and family history study. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:441-446.

- Hudson JI, Pope HGJ. Fibromyalgia and psychopathology: Is fibromyalgia a form of “affective spectrum disorder”? J Rheumatol Suppl. 1989;19:15-22.

- Yunus MB. Primary fibromyalgia syndrome: Current concepts. Compr Ther. 1984;10:21-28.

- Bengtsson A, Henriksson KG. The muscle in fibromyalgia: A review of Swedish studies. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1989;19:144-149.

- Bennett RM, Clark SR, Goldberg L, et al. Aerobic fitness in patients with fibrositis: A controlled study of respiratory gas exchange and 133xenon clearance from exercising muscle. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:454-460.

- Bennett RM. Muscle physiology and cold reactivity in the fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1989;15:135-147.

- Yunus MB. Central sensitivity syndromes: A new paradigm and group nosology for FM fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:339-352.

- Aaron LA, Bradley LA, Alarcon GS, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses in patients with fibromyalgia are related to health care-seeking behavior rather than to illness [see comments]. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:436-445.

- Drossman DA, Li ZM, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569-1580.

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: Update on mechanisms and management. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:102-109.

- Woolf CJ. Pain: Moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:441-451.

- Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA. 1998;280:981-988.

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. A population-based twin study of functional somatic syndromes. Psychol Med. 2008;1-9.

- Buskila D, Sarzi-Puttini P, Ablin JN. The genetics of fibromyalgia syndrome. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:67-74.

- Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Hess EV, et al. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:944-952.

- Williams DA, Brown SC, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM. Self-reported symptoms before and after September 11 in patients with fibromyalgia. JAMA. 2003;289:1637-1638.

- Clauw DJ, Mease P, Palmer RH, Gendreau RM, Wang Y. Milnacipran for the treatment of FM in adults: A 15-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1988-2004.

- Raphael KG, Natelson BH, Janal MN, Nayak S. A community-based survey of FM-like pain complaints following the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Pain. 2002;100:131-139.

- Clauw DJ, Chrousos GP. Chronic pain and fatigue syndromes: Overlapping clinical and neuroendocrine features and potential pathogenic mechanisms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997;4:134-153.

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. Chronic widespread pain and its comorbidities: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1649-1654.

- Giesecke T, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Geisser ME, Petzke FW, Clauw DJ. The relationship between depression, clinical pain, and experimental pain in a chronic pain cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1577-1584.

- Diatchenko L, Nackley AG, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Maixner W. Idiopathic pain disorders—pathways of vulnerability. Pain. 2006 Aug;123(3):226-230.

- Armitage R, Landis C, Hoffmann R, et al. Power spectral analysis of sleep EEG in twins discordant for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:51-57.

- Sherlin L, Budzynski T, Kogan BH, Congedo M, Fischer ME, Buchwald D. Low-resolution electromagnetic brain tomography (LORETA) of monozygotic twins discordant for chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1438-1442.

- Buskila D, Neumann L, Vaisberg G, Alkalay D, Wolfe F. Increased rates of FM following cervical spine injury. A controlled study of 161 cases of traumatic injury [see comments]. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:446-452.

- McLean SA, Clauw DJ. Predicting chronic symptoms after an acute “stressor”—lessons learned from 3 medical conditions. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:653-658.

- Wolfe F. The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: Evidence that FM is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:268-271.

- Wolfe F, Rasker JJ. The Symptom Intensity Scale, fibromyalgia, and the meaning of fibromyalgia-like symptoms. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2291-2299.

- Clauw DJ, Witter J. Pain and rheumatology: Thinking outside the joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:321-324.

- Harris RE, Sundgren PC, Pang Y, et al. Dynamic levels of glutamate within the insula are associated with improvements in multiple pain domains in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:903-907.

- 36. Craig AD. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:500-505.

- Brooks JC, Tracey I. The insula: A multidimensional integration site for pain. Pain. 2007;128:1-2.

- Buskila D, Neumann L, Hazanov I, Carmi R. Familial aggregation in the fibromyalgia syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996;26:605-611.

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. Importance of genetic influences on chronic widespread pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1682-1686.