The issue of toxicities due to CS has prompted the search for other therapies for GCA, especially those with ostensible steroid-sparing qualities. The benefits of methotrexate in this regard have proved to be so-so, at best. A randomized controlled trial showed no benefit for adjunctive infliximab, though the evident value of TNF-alpha blockade in the treatment of Takyasu arteritis, the histopathology of which resembles GCA, suggests that this approach could be further investigated.17 And there are recent anecdotes touting favorable effects of IL-6 blockade with tocilizumab.18 Controlled studies will be essential to ascertain the role for the latter in the management of GCA. If tocilizumab—or any other therapy—facilitates shorter courses of CS in the management of GCA, will CS-related toxicities in fact be reduced? Will side effects of adjunctive treatments themselves be problematic? Would any of these treatments actually be used as monotherapy? Could they match the certain worth of CS in the prevention of vision loss, with lesser toxicity?

More Issues: GCA and Large-Vessel Involvement

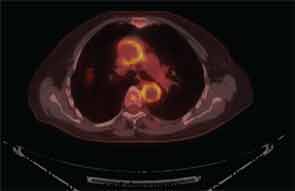

It is now well established that arteries other than the small, above-the-neck, extracranial arteries can be affected by GCA. Findings on FDG PET scanning and arterial ultrasound suggest that subclinical involvement of the large vessels—aorta, great vessels of the neck, and large arteries of the limbs—is common, a major clinical consequence of which is aortic aneurysm, described in 10–18% of reported series (see Figure 3, p. 33).19-22 The questions surrounding the issue of aneurysms in GCA are frustratingly numerous. Who is at risk? What is the relationship to prior CS treatment? What is cost-effective screening? If an aortic aneurysm is identified, how is damage in the arterial wall differentiated from disease activity? What is treatment, and how should it be followed? There are, at present, no good answers, no high levels of evidence to guide decision making. Because appropriate treatment for an asymptomatic aneurysm in patients with GCA is unknown, regular screening with CT of the chest or MRA seems unjustifiable. While we await more robust data, as rheumatologists we must advise patients and their primary physicians as to the potential risk for this issue, and clinical awareness must be sustained, as aneurysms may not manifest for several years after the initial diagnosis of GCA.

A further issue is the discovery of histopathologic aortitis on resection of an apparently routine aneurysm of the ascending aorta. About 5% of these resected aneurysms are inflammatory on histopathologic inspection.23,24 Rare etiologies—e.g., syphilitic aortitis or other infections—are identified in a handful of these cases. Lymphoplasmacytic aortitis, associated with immunoglobulin G-4 disease, is a newly recognized etiology.25 In about one-fifth of cases of inflammatory aortitis, symptoms or signs referable to systemic rheumatic disease—prior PMR or GCA, Takayasu arteritis, relapsing polychondritis, etc.—can be found; the remainder fall under the heading of noninfectious ascending aortitis. Whether this latter subset should be classified along the clinical spectrum of GCA, or understood as a problem sui generis (so-called “isolated aortitis”), is unclear. Work-up and treatment pose challenges similar to the situation of aneurysms occurring in the context of bona fide GCA. Imaging of the arterial tree is warranted, and the acute phase reactants should be measured after the dust has settled from surgery. In the absence of explicit evidence of active inflammation, overtreatment should be avoided, but vigilance for the development of new aneurysms must be maintained, and vascular imaging should be periodically repeated.26