Posterior Knee Swelling: The Popliteal Cyst

The differential diagnosis of posterior knee swelling includes popliteal cyst, lipoma, aneurysm, thrombophlebitis and muscle herniation due to trauma.1

The most common origin of a popliteal cyst is the bursa beneath the medial gastrocnemius muscle, which may coalesce with another bursa under the semimembranosus tendon to form the gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa (GSB).2 The GSB communicates with the healthy native knee joint in 40–54% of the population. 1 When the GSB swells, it is known as a popliteal or Baker’s cyst, named after W. Morant Baker, who described the entity in 1877.3

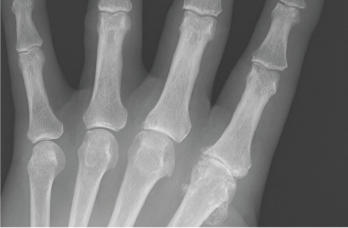

Figure 4: An anteroposterior X-ray of the left hand. Note the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint narrowing of digits 2 and 3, osteophytes at the second MCP joint and only mild osteoarthritis at the proximal interphalangeal joints.

Enlargement of the GSB may be primary or secondary.2 Primary GSB enlargement occurs when there is no communication of the cyst to the joint. Inflammatory polyarthritis with direct involvement of the bursal synovium may cause a primary popliteal cyst.2 Secondary GSB enlargement describes synovial fluid flowing from the joint to the cyst via a communicating channel.2 Excess synovial fluid may result from pathology in a native knee, such as a meniscal tear, degenerative change to cartilage, or an inflammatory arthropathy.1,2

Popliteal cysts often present as asymptomatic swelling in the popliteal fossa with or without posterior knee pain. However, continued enlargement of the popliteal cyst may restrict range of motion and compress adjacent structures, such as the popliteal vein, with resultant secondary thrombophlebitis.1,2 Rarely, compression of the tibial nerve may cause neurological dysfunction.4 With continued enlargement, the popliteal cyst may rupture, resulting in severe pain, and can mimic thrombophlebitis.1,2

Popliteal Cyst after Total Knee Arthroplasty

Although popliteal cysts in native knees are well recognized, descriptions of popliteal cysts following TKA appear in only a few case reports.5-9 It is important to differentiate preexisting popliteal cysts that fail to resolve after TKA from those that arise after the procedure.5 Popliteal cysts arising after TKA may result from a failed knee arthroplasty, characterized by loosening, osteolysis or wear-particle generation.1,6-9 Interestingly, in at least two reported cases, free communication of the popliteal cyst with the TKA occurred.7,8 A poorly functioning knee arthroplasty may generate debris, causing particle-induced synovitis, a sign of a connection between the joint cavity and the popliteal cyst.6

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard to diagnose popliteal cysts, to differentiate them from other causes of posterior knee pain and swelling, and to detect an underlying cause of excessive synovial fluid production in the knee that may generate a secondary popliteal cyst. However, MRI accuracy must be weighed against expense.1 Further, metal implants may generate distortions even when optimized pulse sequences are used.10

By contrast, ultrasound, a low-cost tool unaffected by metallic implants, is a viable screening device with nearly the same sensitivity of MRI, but it is less specific in differentiating popliteal cysts from other causes, such as soft tissue masses.1 Further, ultrasound less often detects underlying knee pathology responsible for the formation of secondary popliteal cysts.1 Another drawback is that ultrasound is user dependent.1

Popliteal cysts have a distinct appearance on ultrasound. If the interior of a popliteal cyst appears anechoic on ultrasound, it likely contains pure synovial fluid; this appearance helps differentiate the popliteal cyst from other soft tissue masses.6 However, when a popliteal cyst offers a mixed picture of heterogeneous echotexture within the bursa, hemorrhage and thickened synovium are possible.11

Ultrasound has proved useful as a point-of-care complement to physical exam by defining synovitis, cortical and cartilage erosion.12-14