A 56-year-old automobile mechanic was referred to our rheumatology service by his orthopedist to evaluate left posterior knee pain and swelling that had been present for three months. The patient had undergone bilateral total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) for sports-related osteoarthritis three years before.

In addition to the knee pain, the patient described several years of bilateral hand swelling and stiffness, which had been worsening over the past few months. He also complained of significant malaise and fatigue over the past six months. He denied a history of spine pain or stiffness, psoriasis or bowel problems.

Physical examination revealed chronic synovitis of the bilateral wrists and metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints and a swelling posterior to the left knee. There was no clinical or X-ray evidence of arthroplasty failure or loosening. Review of the surgical report revealed no posterior left knee mass or bursal enlargement.

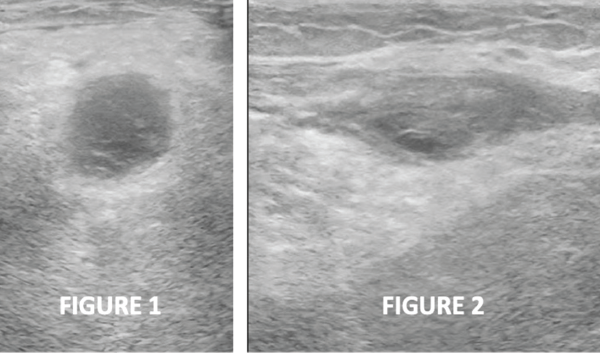

Ultrasound of the left knee demonstrated a cystic mass superficial to the tendons of the medial gastrocnemius and the semimembranosus muscles measuring 1.63 cm in depth and 6 cm in length. The cyst consisted of a mixture of hyper- and hypoechoic areas and a smaller relatively anechoic area. Power Doppler was negative. Careful inspection did not demonstrate a stalk connecting the mass to the arthroplasty (see Figures 1 & 2).

Figures 1 & 2: Transverse and longitudinal ultrasound views, respectively, of the left posterior knee, revealing a cystic mass with heterogeneous internal echotexture and no stalk.

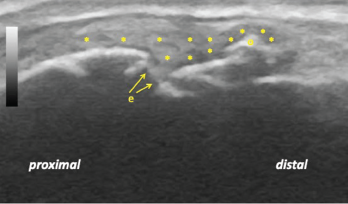

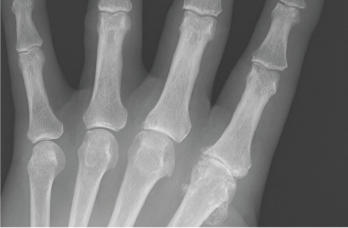

Ultrasound of the left hand confirmed the clinical finding of significant chronic synovitis, as noted by an enlarged dorsal synovial recess filled with hyperechoic material, as well as severe bony and cartilaginous erosion of the second and third MCP joints. Osteophyte formation was noted as well (see Figure 3). Power Doppler was only minimally positive. Left hand X-rays (see Figure 4) corroborated severe MCP narrowing and osteophytes at MCP joints 2 and 3, with mild osteoarthritic change at the proximal phalangeal joints. Opposite hand X-rays demonstrated periarticular cortical erosions of MCP joints 2 and 3. Neither ultrasound nor the X-rays suggested calcium deposition in soft tissues.

Figure 3: Longitudinal ultrasound view of the left second metacarpophalangeal joint demonstrating diffuse synovitis (*), metacarpal head discontinuity due to bone and cartilage erosion (e), and a bony osteophyte (o).

Anti-nuclear antibody, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, rheumatoid factor, serum calcium, angiotensin converting enzyme, Lyme serology, uric acid level, iron studies and a chest X-ray were negative or unremarkable. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal at 15 mm/hour.

The patient declined cyst aspiration. With a working diagnosis of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis (RA), methotrexate (MTX) was prescribed. Weekly MTX administration of 20 mg subcutaneously effected substantial improvement of pain and swelling, but only mild improvement of hand stiffness. Fifty milligrams of subcutaneous etanercept weekly was ordered to improve joint stiffness and fatigue.

Posterior Knee Swelling: The Popliteal Cyst

The differential diagnosis of posterior knee swelling includes popliteal cyst, lipoma, aneurysm, thrombophlebitis and muscle herniation due to trauma.1

The most common origin of a popliteal cyst is the bursa beneath the medial gastrocnemius muscle, which may coalesce with another bursa under the semimembranosus tendon to form the gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa (GSB).2 The GSB communicates with the healthy native knee joint in 40–54% of the population. 1 When the GSB swells, it is known as a popliteal or Baker’s cyst, named after W. Morant Baker, who described the entity in 1877.3

Figure 4: An anteroposterior X-ray of the left hand. Note the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint narrowing of digits 2 and 3, osteophytes at the second MCP joint and only mild osteoarthritis at the proximal interphalangeal joints.

Enlargement of the GSB may be primary or secondary.2 Primary GSB enlargement occurs when there is no communication of the cyst to the joint. Inflammatory polyarthritis with direct involvement of the bursal synovium may cause a primary popliteal cyst.2 Secondary GSB enlargement describes synovial fluid flowing from the joint to the cyst via a communicating channel.2 Excess synovial fluid may result from pathology in a native knee, such as a meniscal tear, degenerative change to cartilage, or an inflammatory arthropathy.1,2

Popliteal cysts often present as asymptomatic swelling in the popliteal fossa with or without posterior knee pain. However, continued enlargement of the popliteal cyst may restrict range of motion and compress adjacent structures, such as the popliteal vein, with resultant secondary thrombophlebitis.1,2 Rarely, compression of the tibial nerve may cause neurological dysfunction.4 With continued enlargement, the popliteal cyst may rupture, resulting in severe pain, and can mimic thrombophlebitis.1,2

Popliteal Cyst after Total Knee Arthroplasty

Although popliteal cysts in native knees are well recognized, descriptions of popliteal cysts following TKA appear in only a few case reports.5-9 It is important to differentiate preexisting popliteal cysts that fail to resolve after TKA from those that arise after the procedure.5 Popliteal cysts arising after TKA may result from a failed knee arthroplasty, characterized by loosening, osteolysis or wear-particle generation.1,6-9 Interestingly, in at least two reported cases, free communication of the popliteal cyst with the TKA occurred.7,8 A poorly functioning knee arthroplasty may generate debris, causing particle-induced synovitis, a sign of a connection between the joint cavity and the popliteal cyst.6

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard to diagnose popliteal cysts, to differentiate them from other causes of posterior knee pain and swelling, and to detect an underlying cause of excessive synovial fluid production in the knee that may generate a secondary popliteal cyst. However, MRI accuracy must be weighed against expense.1 Further, metal implants may generate distortions even when optimized pulse sequences are used.10

By contrast, ultrasound, a low-cost tool unaffected by metallic implants, is a viable screening device with nearly the same sensitivity of MRI, but it is less specific in differentiating popliteal cysts from other causes, such as soft tissue masses.1 Further, ultrasound less often detects underlying knee pathology responsible for the formation of secondary popliteal cysts.1 Another drawback is that ultrasound is user dependent.1

Popliteal cysts have a distinct appearance on ultrasound. If the interior of a popliteal cyst appears anechoic on ultrasound, it likely contains pure synovial fluid; this appearance helps differentiate the popliteal cyst from other soft tissue masses.6 However, when a popliteal cyst offers a mixed picture of heterogeneous echotexture within the bursa, hemorrhage and thickened synovium are possible.11

Ultrasound has proved useful as a point-of-care complement to physical exam by defining synovitis, cortical and cartilage erosion.12-14

Case Discussion

In this case, ultrasound of the posterior knee revealed an isolated (noncommunicating) popliteal cyst with a mixed echogenic picture, as well as chronic synovitis, cartilage and bone erosive arthropathy in the MCP joints. In this clinical setting, the development of a popliteal cyst was tentatively concluded to be the result of synovitis of the bursal lining, perhaps mechanically aggravated by knee movement of an intact and functional TKA. A more definitive diagnosis of rheumatoid bursitis may have been obtained if aspiration and synovial biopsy of the cyst had been permitted.

The diagnosis of seronegative RA was based on clinical presentation, hand ultrasound, X-rays and the lack of evidence for another erosive polyarthritis. There was no clinical or surgical evidence of the popliteal cyst preexisting the TKA or of TKA failure or loosening.

Treatment with MTX was initiated to treat the popliteal cyst and hand synovitis, as well as systemic features of fatigue and malaise. The popliteal cyst could have been directly injected, but the patient required additional systemic treatment due to his disease activity, irrespective of the efficacy of a popliteal cyst injection.

Alternatively, the presumed synovitis of the popliteal cyst may have been from particle-induced synovitis. However, the lack of communication with the TKA argues against particle-induced synovitis.6 A positive response to MTX offers evidence, albeit inconclusive, that underlying popliteal cyst synovitis was due to the active RA because since experimental evidence in mice indicates MTX may have a salutary effect on wear-particle-induced inflammatory osteolysis.15

Conclusion

Ultrasonography has become the method of choice for initial screening for popliteal cysts in recent years.1 MRI remains the gold standard in diagnosing popliteal cysts; however, the low cost, noninvasiveness and lack of radiation make ultrasound appealing.1

In our clinic, ultrasound often demonstrates communication between the popliteal cyst and the joint, thus guiding treatment. If a direct communication between the popliteal cyst and the TKA is present, then injection of the popliteal cyst must be approached cautiously due to the potential for seeding an infection into the prosthetic joint.

Finally, popliteal cyst formation after total knee arthroplasty may not necessarily be the result of a malfunction, and a search to define the nature and source of the popliteal cyst should be undertaken.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, completed his rheumatology fellowship at the Albert Einstein-Montefiore Medical Center, The Bronx, N.Y. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Mark H. Greenberg, MD, RMSK, RhMSUS, completed his rheumatology fellowship at the Albert Einstein-Montefiore Medical Center, The Bronx, N.Y. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Prem Patel is a second-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia. He graduated from the University of South Carolina with a Bachelor of Science in biomedical engineering.

Prem Patel is a second-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia. He graduated from the University of South Carolina with a Bachelor of Science in biomedical engineering.

Elijah Mitcham, MD, graduated from Mercer University School of Medicine, Georgia, and completed his internal medicine residency at Palmetto Health/University of South Carolina.

Elijah Mitcham, MD, graduated from Mercer University School of Medicine, Georgia, and completed his internal medicine residency at Palmetto Health/University of South Carolina.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

James W. Fant Jr., MD, completed his rheumatology fellowship at Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. He is board certified in internal medicine and rheumatology. He is an associate professor of medicine at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Division at Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, Columbia, S.C.

Frank R. Voss, MD, earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, Boston, completed a general surgery residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his orthopedic surgery residency at Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Program. He completed a fellowship in reconstructive surgery at Rush-

Frank R. Voss, MD, earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, Boston, completed a general surgery residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his orthopedic surgery residency at Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Program. He completed a fellowship in reconstructive surgery at Rush-

Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago. He is an associate professor of orthopedic surgery, director of medical education for orthopedic surgery and the department’s vice chair at University of South Carolina School of Medicine. He is board certified in orthopedic surgery.

References

- Frush TJ, Noyes FR. Baker’s cyst: Diagnostic and surgical considerations. Sports Health. 2015 Jul;7(4)359–365.

- Fritschy DJ, Fasel J, Imbert JC, et al. The popliteal cyst. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006 Jul;14(7)623–628.

- Baker WM. On the formation of synovial cysts in the leg in connection with disease of the knee-joint. 1877. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994 Feb;(299):2–10.

- Ji JH, Shafi M, Kim WY, et al. Compressive neuropathy of the tibial nerve and peroneal nerve by a Baker’s cyst: Case report. Knee. 2007;14(3):249–252.

- Tofte JN, Holte AJ, Noiseux N. Popliteal (Baker’s) cysts in the setting of primary knee arthroplasty. Iowa Orthop J. 2017;37:177–180.

- Moretti B, Patella V, Mouhsine E, et al. Multilobulated popliteal cyst after a failed total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007 Feb;15(2):212–216.

- Dirschl DR, Lachiewicz PF. Dissecting popliteal cyst as the presenting symptom of a malfunctioning total knee arthroplasty. Report of four cases. J Arthroplasty. 1992 Mar;7(1):37–41.

- Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, et al. Gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003 Dec;18(8):1071–1075.

- Hsu WH, Hsu RW, Huang TJ, et al. Dissecting popliteal cyst resulting from a fragmented, dislodged metal part of the patellar component after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002 Sep;17(6):792–797.

- Fritz J, Lurie B, Potter HG. MR imaging of knee arthroplasty implants. Radiographics. 2015 Sep–Oct;35(5):1483–1501.

- Ward EE, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP, et al. Sonographic detection of Baker’s cysts: Comparison with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001 Feb;176(2):373–380.

- do Prado AD, Staub HL, Bisi MC, et al. Ultrasound and its clinical use in rheumatoid arthritis: Where do we stand? Adv Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 2;58(1):19.

- Wakefield RJ, Gibbon WW, Conaghan PG, et al. The value of sonography in the detection of bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A comparison with conventional radiography. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Dec;43(12):2762–2770.

- Filippucci E, da Luz KR, Di Geso L, et al. Interobserver reliability of ultrasonography in the assessment of cartilage damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Oct;69(10):1845–1848.

- Mediero A, Perez-Aso M, Wilder T, et al. Methotrexate prevents wear particle-induced inflammatory osteolysis via activation of the adenosine A2A receptor. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Mar;67(3):849–855.