Elbow

Although most participants found the elbow scan easier in general, some had difficulty identifying the lateral epicondyle and instead ended up scanning the humerus more proximally over the supracondylar ridge at the brachioradialis origin. Palpation of bony landmarks, such as the lateral epicondyle, can help the sonographer properly place the transducer on the target tissue—thus promoting serenity in tennis elbow evaluation—and should be emphasized by instructors.

Shoulder

The shoulder region has perhaps the greatest differences in depth between tissues of interest for various views. The acromioclavicular joint can be less than a centimeter deep to the skin, whereas the glenohumeral joint can be more than 4 cm deep. Thus, adjustment of depth, focal zones and frequency may all be needed when switching from one view to the next. Many students struggle to keep up with proper setting adjustments. Many also struggle to recognize tendon abnormalities despite scanning through the abnormalities. These students are focused on finding normal looking tissue and may assume that abnormalities are due to their technique rather than tissue pathology.

Hip

Although almost all students were able to properly identify the hip joint capsule, many adjusted their measurement of the capsule-to-femur distance to what they expected to find (i.e., a normal joint) rather than the full measurement, which happened to be particularly large in their healthy model. This was a repeated pattern throughout the practical exam: Students would first decide what they expected to see, then try to adjust the ultrasound image to fit their preconceived ideas rather than vice versa.

A few students forgot to examine the region with Doppler settings in planning a potential hip injection. The transverse branch of the lateral circumflex artery frequently lies in the path of the needle for a hip injection and should be identified.3

Finally, “toeing in” (applying more pressure with the distal edge of the transducer relative to proximal) can help visualize the hip capsule by reducing capsular anisotropy. However, the sonographer needs to be cognizant of the tissue pressure applied in employing this technique, especially in patients with substantial pannus over the inguinal crease, because atrophic skin can be injured by excessive transducer pressure.

Knee

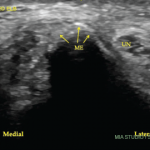

Essentially all students were facile with the anterior view, but up to a fifth struggled to identify a Baker’s cyst on the posterior transverse view because they could not properly position the transducer on the three landmark structures: the medial femoral condyle, the semimembranosus tendon and the medial gastrocnemius muscle/tendon. Most of the students who struggled positioned the transducer too far distally. The medial femoral condyle is most easily distinguished from the proximal tibia by the thick layer of anechoic hyaline cartilage overlying the bone of the medial femoral condyle. Some students also erroneously identified anisotropic tendons as Baker’s cysts. See Figure 2 for the illumination of the disappearing Baker’s cyst.

Rocking the probe and sonopalpation (to assess compressibility) are two helpful techniques to avoid this pitfall.