Audit activity among Medicare and most third-party payers has increased in response to pressure to reduce healthcare costs. The return of billions of dollars to Medicare, Medicaid and third-party programs through these medical audit reviews has also increased. For example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) 2014 Annual Report estimated that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recouped $36 billion in improper payments from fee-for-service claims under both Medicare Part A and B. This is mainly attributed to the fact that payers have access to providers’ claims data, along with other software programs that allow payers to review claims and billing patterns in an effort to identify the potential for inappropriate billing and fraud.

The most common reasons a provider might be audited include inadequate documentation, unbundling of services, upcoding, inappropriate balance billing and routine waiver of copayments, coinsurance or deductibles. Due to vulnerabilities in provider programs, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has requested ongoing investigations related to coding and billing. CMS created the Medicare contractor programs to assist other federal efforts in identifying and pursuing healthcare fraud and abuse. The five

Medicare review contractors include:

Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs)

The MACs are responsible for processing and paying Medicare claims and establishing regional policy guidelines, called Local Coverage Determinations (LCD). Because MACs are in the thick of Medicare reimbursement, they are also tasked with identifying overpayments and providing outreach and education to prevent future inappropriate billing.

Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs)

The RAC program began in 2005 as a CMS demonstration program, and has since become permanent. RACs provide additional review of Medicare claims for payment. The goal of RACs is to identify and correct improper payments three years before the start of an audit. The document requests vary by provider type. RACs are paid on a contingency fee basis, and therefore, are highly motivated to identify and collect overpayments.

Supplemental Medical Review Contractors (SMRCs)

The SMRC has the primary task of conducting nationwide medical review as directed by CMS. Medical review is the evaluation of medical records and related documents to determine whether Medicare claims were billed in compliance with coverage, coding, payment and billing guidelines. CMS has contracted with StrategicHealthSolutions, LLC as the SMRC for the entire U.S.

Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT)

The Medicare CERT program was implemented as a mechanism for CMS to assess whether MACs are properly paying claims. The CERT program determines the national Medicare fee for service improper payment rate, which is published on an annual basis.

The national improper payment rate is calculated based on a stratified random sample of Medicare fee-for-service claims. The claims are reviewed, documentation is collected and reviewed, and ultimately, the national improper payment rate is calculated based on the percentage of the claims reviewed that were improperly paid.

Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs)

Of all the CMS claim review contractors, ZPICs present a particular set of danger to the unsuspecting provider. The ZPICs focus primarily on fraud and abuse, meaning they concentrate on uncovering overpayments resulting from intentional deviations from normal billing practices. Therefore, if a provider receives a ZPIC audit request, it’s because the provider is the subject of a fraud investigation, or the ZPIC is investigating to determine if a fraud investigation should be opened.

Because the CMS has tasked ZPICs with uncovering fraud, the CMS has granted ZPICs broader powers than other Medicare contractors. ZPICs do not have a look-back period, meaning ZPICs do not have to limit their review of claims to recent years. ZPICs also have unlimited document requests and can conduct on-site visits to interview providers, beneficiaries and employees.

If the ZPIC finds billing errors or any other irregularities that resulted in an overpayment, the matter will be referred to the MAC for an overpayment recoupment or implementation of a prepayment review. On the other hand, if the investigation uncovers the possibility of fraud it will then become a case, in which the investigation will be closed and the case referred to the OIG and the U.S. Department of Justice.

Responding to an Audit

Whether from Medicare or a third-party payer, any audit letter/request must be taken seriously. Sometimes, it may be a postpayment review or an educational notice, but regardless of whom the payer may be or what they state in the letter, all inquiries should be discussed with all providers, practice administrator(s) and coding/billing staff. Second, evaluate the stated reason for the audit, take careful note of how many charts and what other documentation is requested for review and make sure to record the deadline to provide the requested information.

The provider or practice manager should determine the point person responsible to complete the payer request and gather all information. Prepare to provide the materials, which may include medical records, invoices for drugs and supplies, and any other reference materials. Do not rush the process, but make sure to meet the payer deadlines. Too often, employees rush to get the information out to the payer and miss something, which can be costly to the practice. Also, do not send original forms or invoices—only copies should be sent to the payer unless they specify otherwise in the request. Hiring an outside auditor or having the ACR auditors review a sample of claims can be beneficial, since they are trained to spot any potential issues and can provide the appropriate next steps.

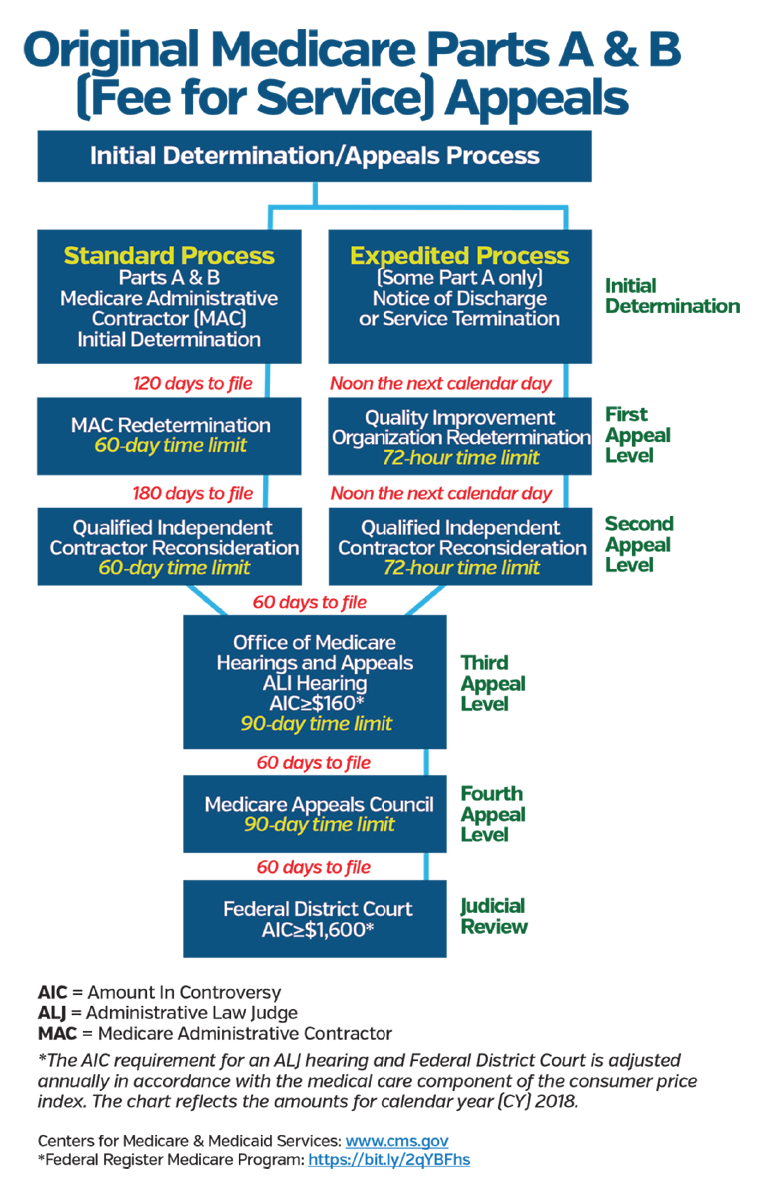

If there is no action against the provider at the end of the review, the practice should take proactive measures to conduct an internal/external review of a random sample of charts to correct any issues that were the focus of the payer audit. If for any reason the audit is not favorable, any claim that is denied should be reviewed for possible appeal. Make sure to visit the private payer’s website for its appeals process. For Medicare, the appeal process has five levels for denied claims:

- Redetermination from the intermediary/carrier;

- Reconsideration from a qualified independent contractor;

- Appeal to an administrative law judge;

- Appeal to the Medicare Department Appeals Board; and

- Appeal to a federal district court.

To protect your practice, it is imperative to know the appeal timeliness and requirements for each level of appeal, understand the reasons for denial at each level and be aware of recoupment timing. During the brief pause in the appeals process, establish an appeals team, which can include one or more of the following: provider(s), practice manager, coder, compliance officer and/or legal counsel. Every claim for possible appeal should be reviewed to ensure the auditors complied with correct coding guidelines and current medical policies.

Keep in mind, if there is a recoupment request and Medicare does not receive payment within 40 calendar days from the date of the MAC’s first demand letter, Medicare will recoup the full overpayment amount beginning on day 41, meaning the overpayment will be recovered from current payments due or from future claims submitted. In an effort to delay recoupment while performing an internal analysis, submit a rebuttal to your MAC within 15 days of the initial demand letter (no guarantee) and file appeal requests for the first two levels of appeal within specified time frames. Specifically, a provider must file the first-level appeal within 30 days of the initial demand letter to prevent recoupment through the time that a redetermination decision issues. If the redetermination decision is unfavorable, the provider must file the second-level appeal within 60 days of the redetermination decision. If the reconsideration decision is also unfavorable, Medicare will initiate recoupment 30 days after the reconsideration decision is issued. If the reconsideration is partially favorable, and the overpayment sum requires recalculation, recoupment will begin 30 days after the recalculated demand.

Although audits may seem scary, proper preparation and proactive measures can be put in place to mitigate the chance of being audited and protect providers, their staff and the overall practice. Most experts agree the best defense is a good offense. It is important to assess the risk of an audit before it occurs, because unfavorable audits jeopardize the financial viability of a practice. Although it may create more work initially, experts agree that performing a minimum of two internal audits per year may ultimately help reduce any external ones; quarterly internal audits are recommended.

Ultimately, the best line of defense for a practice is implementing a comprehensive compliance plan with policies and procedures for education and training; conducting practice data mining, internal monitoring and auditing; and implanting corrective measures for identified problems.

For questions on creating a practice compliance plan, chart audits or training on self-audits, contact the ACR practice management department at [email protected].